Indiana Court of Appeals rules 2–1: Bloomington’s definition of fraternity delegated undue authority to Indiana University

In a ruling issued Thursday, a three-judge panel from the Indiana Court of Appeals ruled 2–1 to uphold a lower court ruling: The definition of a fraternity or sorority in Bloomington’s zoning code violates the US Constitution because it delegates to Indiana University the city’s authority to determine zoning compliance.

Author of the opinion was Rudolph Pyle with Marget Robb concurring. Issuing a dissenting opinion was L. Mark Baily.

Owing in part to the ongoing litigation, last year in early December, the definition of a fraternity or sorority house was amended by Bloomington’s city council. The amendment came during the council’s consideration of myriad other amendments to the city’s updated unified development ordinance (UDO).

At that time, city attorney Mike Rouker told the city council that the definition was the subject of litigation, but the city’s legal department believed that the existing language defining a fraternity/sorority is constitutional. The amendment approved by the city council eliminated potential controversy by removing any specific mention of Indiana University, Rouker told the council.

Thursday’s court of appeals ruling was about the unamended version of the UDO definition, which mentioned IU specifically.

The updated UDO is not yet effective. The effective date will coincide with the city council’s adoption of the zoning conversion map, which still needs to undergo review by the city’s plan commission. Adoption by the council of the conversion map is hoped to be done before the council takes its summer break.

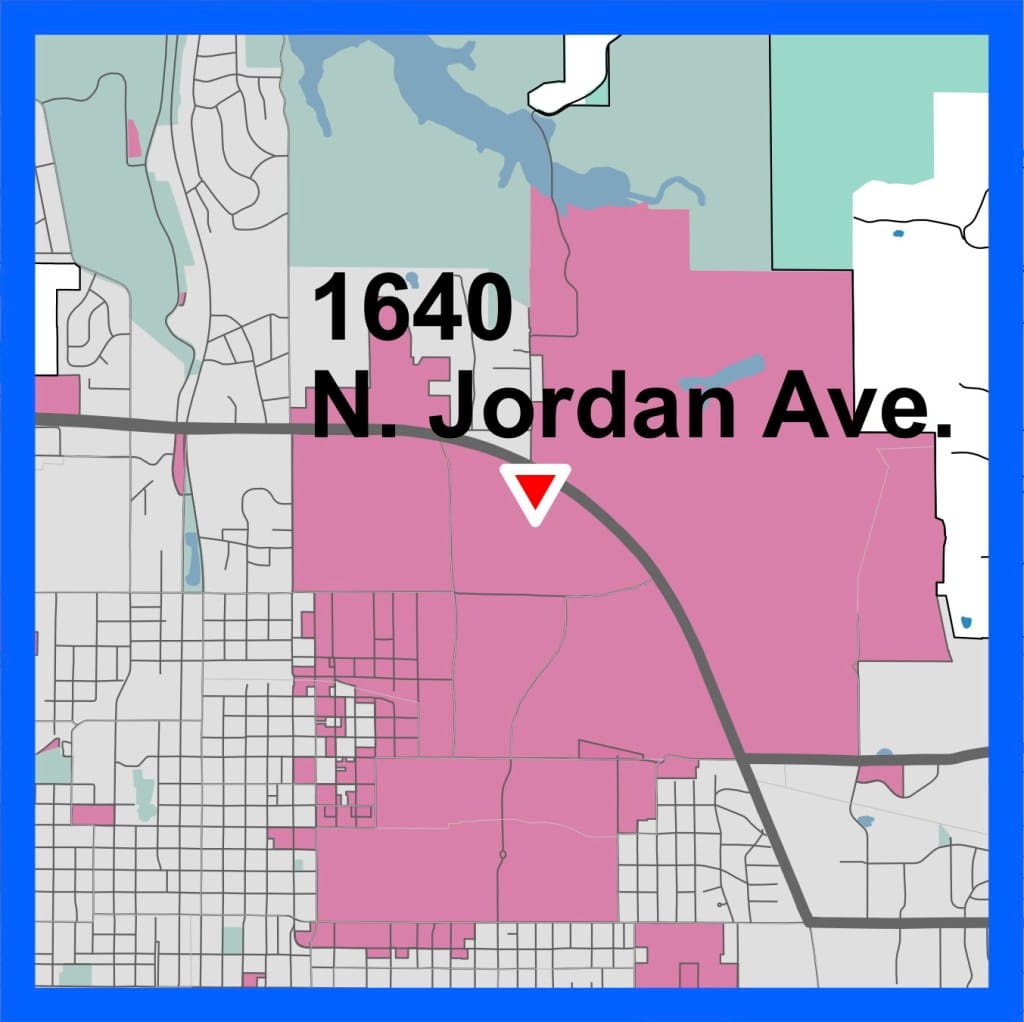

Once the new definition is operative, will the city of Bloomington enforce the new definition at 1640 N. Jordan Avenue—the property where Bloomington’s attempted enforcement two years ago resulted in legal action from the owner, UJ-Eighty Corporation?

City attorney Mike Rouker responded to the Square Beacon’s question by saying: “The City will seek to enforce any land use violations brought to its attention. If there is a municipal violation at this property, we will treat it the same as any other municipal violation that we learn of.”

Where did this case come from? Starting in 2016, UJ-Eighty Corporation was leasing the property to Gamma-Kappa Chapter of Tau Kappa Epsilon, Inc. The case stemmed from Indiana University’s revocation of the fraternity’s sanction in early February of 2018. Not all of the residents of the fraternity house left the premises, so the city of Bloomington issued a notice of violation.

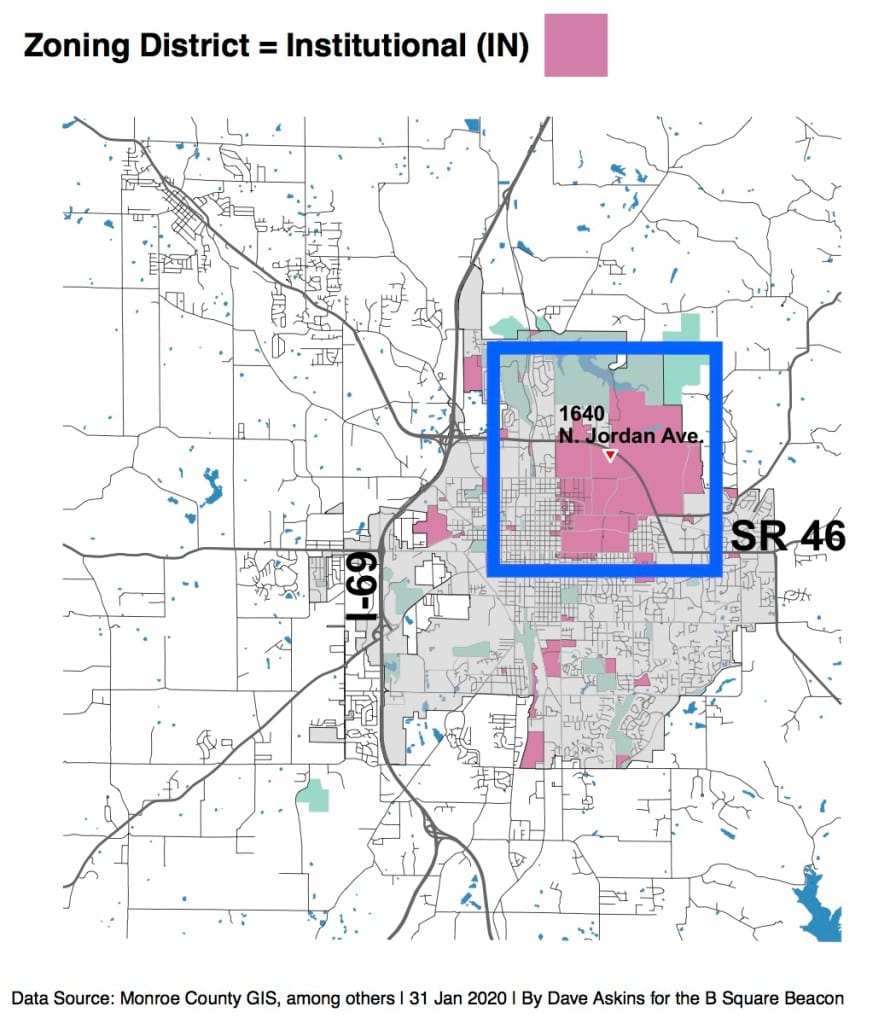

Why did Bloomington analyze the situation as a violation of the zoning code? The area is zoned as an institutional district (IN), which includes a fraternity or sorority house as a permitted use. But under the city’s definition of a fraternity or sorority house at the time, the requirements for residents of a fraternity house included:

…Indiana University has sanctioned or recognized the students living in the building as being members of a fraternity or sorority through whatever procedures Indiana University uses to render such a sanction or recognition.

Once IU revoked TKE’s sanction, the requirement in the definition was no longer met.

When UJ-Eighty did not get satisfaction from the city’s board of zoning appeals, the case went to the Monroe Circuit court, which found in the UJ-Eighty’s favor.

Beyond the specific mention of Indiana University in the definition, in its complaint, UJ-Eighty pointed to the vague wording in the ordinance: “whatever procedures Indiana University uses.” That vagueness leaves it entirely to the university to decide whether a fraternity is sanctioned by whatever criteria it chooses, and by implication whether the use of the property is allowable under the zoning code, UJ-Eighty said. That’s something the city is supposed to do by its own authority, according to UJ-Eighty’s argument.

In his dissenting opinion, Judge L. Mark Baily starts with the idea that in such cases, the ordinance is supposed to be presumed to be constitutional, with the burden of showing it unconstitutional falling on the plaintiff. That is, the plaintiff has to show that the ordinance is unconstitutional.

Among other points, Baily’s dissent responds to UJ-Eighty’s contention that the ordinance should have included guiding standards for Indiana University to determine whether a fraternity should be sanctioned.

The dissent says that IU’s own standards are already subject to constitutional obligations. And there was no demonstration by UJ-Eighty that the standards set by Bloomington—as opposed to those adopted by Indiana University—would better protect against UJ-Eighty’s erroneous deprivation of its interest in renting out its property to TKE, according to the dissent.

The city did not use outside counsel for the case. City attorney Mike Rouker could not say on Friday whether the city would appeal the case to Indiana’s Supreme Court.

Comments ()