Bloomington police respond to records request, release footage of Seminary Park welfare check on man found dead hours later on Christmas Eve

In Seminary Park, on the bench at the corner of 2nd and Walnut Streets in downtown Bloomington, a memorial plaque for James “JT” Vanderburg is now set to be installed.

It’s the place where Vanderburg died last year on Christmas Eve, three days after his 51st birthday. At the time, he was without another place to stay.

The plaque was paid for by the public defender’s office and other community members. The epitaph will read: “The dead cannot cry out for justice. It is the duty of the living to do so for them.”

The Bloomington police department’s press release about Vanderburg’s death stated that officers responded to the park around 11:40 a.m. A passerby had been asked to call 911, according to the release, “because a man was lying on the ground in the park and was believed to be deceased.”

According to the press release, “[S]everal people had tried to get the man services the previous evening and had offered for him to stay with them overnight, but the man refused and slept in the park.”

The press release also stated, “Officers from BPD had checked his welfare once during the evening hours of December 23rd and twice on the morning of December 24th, but the man was sleeping and refused any assistance.”

What did those three welfare checks look like? What kind of assistance was offered?

On Thursday, Feb. 25, the city of Bloomington responded to a records request made last year by The Square Beacon, under Indiana’s Access to Public Records Act (APRA).

In response to the APRA request, the city released the two pieces of bodycam footage that it was able to locate in connection with the welfare checks on Vanderburg.

Bloomington’s chief of police Mike Diekhoff and mayor John Hamilton’s office have indicated to The Square Beacon that they don’t see anything in the bodycam footage that causes them concern.

Bloomington Homeless Coalition board member Marc Teller reacted this way: “This bodycam footage shows exactly what many of us have been saying: The city of Bloomington, its police department, and its leadership are responsible for the death of JT. The officers have blood on their hands. The mayor has blood on his hands. And the administration has blood on its hands.”

Some others who have reviewed the footage have found it to be ambiguous.

One piece of bodycam footage is from the evening of Dec. 23. The other is from the morning of Dec. 24.

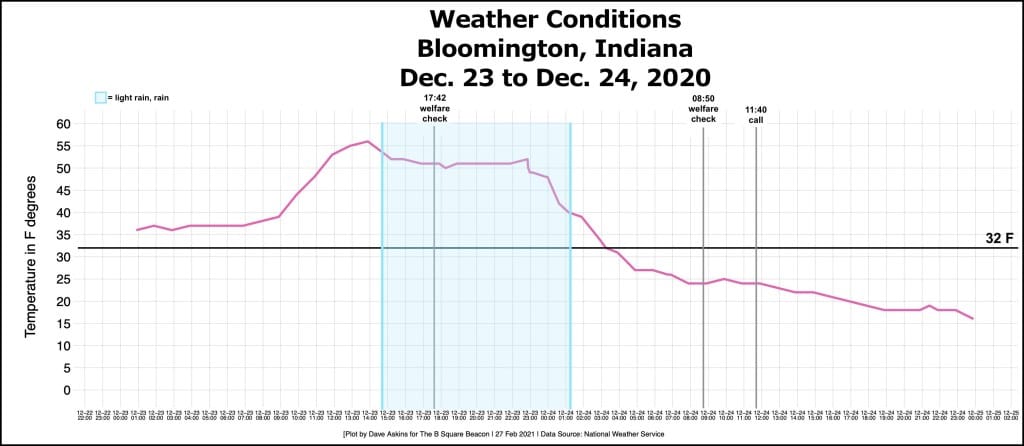

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is five hours earlier than Bloomington time. Based on the GMT timestamps on the videos, the welfare check on Dec. 24 came around 8:50 a.m., or about three hours before Vanderburg was found deceased.

What does the video show?

Measured from the point when the officer opens the door to his patrol car to the time the check has concluded, the Dec. 23 check was completed in around 45 seconds. The Dec. 24 check was completed in about 1 minute and 5 seconds.

In both cases, the footage shows that an officer contacted two men lying on the ground, partly or mostly on the sidewalk, near the park bench at the corner of 2nd and Walnut Streets. There is no tent. Sources have confirmed to The Square Beacon that the man lying towards the south end of the bench is Vanderburg.

In the first video, from the evening of Dec. 23, Vanderburg is under some kind of covering. It’s raining at the time. In the second video, from the morning of Dec. 24, the rain has stopped and he has no covering other than the clothes he’s wearing.

According to National Weather Service observations, the temperature at the time of the Dec. 24 welfare check was about 24 F degrees. That reflected nearly a 30-degree drop from the time of the first welfare check.

The cause of death, provided by Monroe County coroner Joanie Shields, confirms that cold temperatures contributed to Vanderburg’s death: “The final ruling on Cause of Death for Mr. Vanderburg has been ruled as Cardiac Arrhythmia, due to Complications of Chronic Alcoholism, with a contributory cause of Hypothermia. His manner of death has been ruled Natural.”

Context of Seminary Park clearances

Vanderburg’s death has been cited by Bloomington’s mayor, John Hamilton, as illustrating why camping in the wintertime is not a safe alternative for Bloomington’s houseless population, and not an option that he supports.

A counter to the mayor’s position has come during commentary from the public during regular meetings of the city council since Vanderburg’s death: He was without a tent and other gear that might have protected him better from the elements, because of Hamilton’s decision to clear the Seminary Park encampment in early December. People’s tents and other belongings were transported to an offsite location, where people were supposed to be able to claim them.

A second clearance of the park was made by the city in mid-January.

The conditions under which the city is allowed to displace an established public park encampment of people experiencing homelessness is the subject of legislation currently pending in front of the Bloomington city council.

Transcript of footage

In transcribed form, here’s how the bodycam interactions unfolded between BPD and the people on whom officers conducted welfare checks on Dec. 23 and Dec. 24, 2020.

Evening Dec. 23, 2020 Welfare Check

BPD: Hey guys, police department. Police department.

Person1: [?? barely audible]

BPD: I just got to make sure you’re alive. People are calling on you.

Person1: [?? barely audible. Possibly: “I’m good, buddy.”]

BPD: You’re good? What about your friend here? Can you wake him up for me? Just so…

Person1: I don’t know who that is.

BPD: OK. Hey. Hey, buddy. Police department. Police department. Are you alive? I’m just making sure you’re OK ’cause people are calling on you, all right?

Person2: Why?

BPD: Because they, they think that you’re hurt or something. But I’m, I’m just making sure that you’re breathing. You’re good, man. Relax. I’m just making sure you’re OK.

Person2 or Person1: [?? barely audible. Possibly: “Thanks, bud.”]

BPD: I appreciate it. Stay dry. Thank you. 16-38 you can disregard. They’re just sleeping.

Morning Dec. 24, 2020 Welfare Check

BPD: [addresses Person2] Hey, bud. Police. Hey, can you wake up for me? Someone called and worried about ya. Can I help you with anything? Hey, can you wake up just a little bit so you can talk to me?

Alright. [?? not intelligible] sleeping.

[after walking north to address Person2] Hey. Are you alive? Hey.

Person 1: [?? not intelligible]

BPD: Are you alive?

Person 1: [?? barely audible. Possibly: “I’m alive.”]

BPD: Alright, thanks, bud.

Radio: Do you have an extension? The subject from the earlier call wants to speak to an officer.

Reaction to footage

Based on the words exchanged, the footage alone does not appear to provide clear evidence to support the statement in the BPD press release that says the man who was found deceased “refused any assistance.”

About the first piece of footage, Bloomington Homeless Coalition board member Marc Teller said, “At no time during this interaction did the officer even mention ‘shelter’. No offer was given for reprieve from the elements.”

Teller added, “The officer drives off leaving these men in the exact same situation he found them in. Except they were bothered and probably scared. This is absolutely sickening.”

The part of the footage that might be counted as an offer of assistance is the question from BPD: “Can I help you with anything?” But that does not appear to have received a response from Vanderburg, because the officer follows up with, “Hey, can you wake up just a little bit so you can talk to me?”

At that point in the footage, Vanderburg does not appear to respond to the officer’s verbal communication or the nudging of Vanderburg’s knee with the officer’s own lower leg. Vanderburg is not consistently in the frame of the camera during the interaction.

The footage appears to show that the BPD officer concluded Vanderburg was sleeping and then turned his attention to the other man lying on the ground.

Teller described that portion of the video this way: “The officer has been nudging and speaking to him with no movement from JT and no verbal response, either. After nudging a limp, unresponsive body, the officer seems to be satisfied.”

Teller added, “No further attempt at waking JT is made, no ambulance called.” Teller concluded, “From what it looks like in this video, a Bloomington police officer left an unhoused man dead on the streets.”

Bloomington chief of police Mike Diekhoff stated to The Square Beacon that he has been told that, in fact, there was a verbal response from Vanderburg.

Bloomington city councilmember Isabel Piedmont-Smith is a co-sponsor of the ordinance currently pending before the city council that would provide some protection for people experiencing homelessness.

Asked if the welfare checks shown on the bodycam footage were consistent with her expectations as a councilmember, Piedmont-Smith told The Square Beacon: “It’s hard to comment when I don’t know any more than what I see on the videos. If I consider only what I can see on the videos, it seems like the…(daytime) welfare check was not thorough enough. But again, I can’t really judge just based on these videos.”

About the ordinance Piedmont-Smith is sponsoring, Teller said, “At this point all we can do is show support for Ordinance 21-06, which would provide space for these folks where this horrible thing won’t happen.”

Teller added, “We as a community let this happen, and we can’t allow it anymore. These officers, and the entire PD along with the chief, should be held accountable.”

Forrest Gilmore, executive director of Beacon, Inc., a nonprofit that provides shelter and support to houseless people in Bloomington, said after viewing the footage: “Losing JT was heartbreaking for all of us who loved him. We all failed him that Christmas Eve.”

Gilmore added, “In this country of such wealth, that anyone should die from hypothermia lying on his back on a city street is a reflection of our skewed priorities and a challenge to live up to our greatest ideals. Let us become the community we are meant to be by taking seriously the call to care for the least of these.”

Representing BLM B-town core council, Jada Bee said about the welfare checks shown in the footage, “[The men who were being checked on] certainly didn’t want to be bothered, which is neither here nor there. It’s [the officer’s] job to ensure that people are actually okay. And he very clearly didn’t do that.”

Jada Bee added, “I do not believe that the definition of a welfare check is: ‘Are you alive?’ I don’t believe that that’s what it is. You’re supposed to actually assess whether they need medical attention.” Jada Bee said the performance of BPD was “criminally negligent.”

What is a welfare check?

Diekhoff told The Square Beacon he did not see anything in the encounters on the bodycam footage that caused him concern.

It’s the same message that was conveyed from the mayor’s office about the bodycam footage. Yael Ksander, communications director for the city, said that she’d sent the bodycam footage to the mayor. Ksander said that the mayor and others in the administration “did not see anything that they thought was out outside of the norm, of what a welfare check made in response to a call for service to the police looks like.”

Diekhoff told The Square Beacon that the Bloomington police department does not have a policy on exactly how a welfare check is supposed to be handled. Every welfare check is different, he said, and it would be impossible to have a policy that covered every possible situation. Welfare checks are covered during the field training phase for new officers, Diekhoff said.

Diekhoff’s description is consistent with the characterization of welfare check training described to The Square Beacon by Timothy Horty, who is executive director of the Indiana Law Enforcement Academy.

Horty said, “There is no lesson plan or curriculum at the Academy that addresses welfare checks specifically.” Horty added, “Homeless welfare checks are difficult because quite often the individual does not want help from the police. Many times they have mental illness or addiction issues and refuse assistance from shelters and other facilities.”

Horty continued, “It goes without saying they deserve law enforcement attention if in harm’s way or need immediate detention for their own safety.”

Horty concluded, “Each situation is different and officer discretion plays a role in the decision.”

Wendy Scott, who is director of adult protective services (APS) in the Monroe County Prosecutor’s Office could not comment on BPD’s response to the welfare check as shown in the footage. [The Square Beacon did not provide the footage to APS.]

But Scott provided some general information about the way APS handles a request to check on someone who is homeless.

When Adult Protective Services receives a request to check on someone who is homeless, it can be difficult because we are not an emergency response service, so we are not always immediately able to get to the location where the person is. There are three investigators in our office and we cover three counties. We do receive regular calls on individuals who are homeless and usually try and locate them through Shalom, Centerstone, the hospital, Wheeler Mission or through a friend or relative.

There are times when we have no way to locate homeless individuals and not all of them meet criteria as an “endangered adult” as outlined in Indiana APS Statute. An endangered adult is someone who is 18 years of age or older who has some type of mental incapacity or significant physical incapacity which prevents the individual from managing his or her own care.

In the event that we are able to meet with an individual who is endangered and is at risk of abuse, neglect, or exploitation, our investigators make attempts to get information from a medical doctor regarding their opinion regarding the individual’s mental and physical condition. If the person lacks capacity, and we do not have safe options and/or services for that person, we look at petitioning the court for emergency protective services or guardianship.

—Wendy Scott, director of adult protective services (APS)

Role of police in serving the houseless community

Diekhoff told The Square Beacon that BPD had done dozens of welfare checks on Vanderburg. So Vanderburg was familiar to officers, Diekhoff said, and he did not want to be involved with the police.

“Some people want us to be there. Others don’t, they just want to be left alone,” Diekhoff said

Diekhoff told The Square Beacon it’s possible that the city’s approach to dispatching on such calls could be reviewed. He said one approach that could be explored would be to send the ambulance service to such calls. One potential problem that Diekhoff identified with that approach would be the increased volume of ambulance service calls.

As part of the 2021 city budget, two social workers have been added to the police department, bringing the total to three.

One advantage to the additional level of social worker staffing was described during the budget presentation: A social worker can be on shift for a greater part of the day, increasing the likelihood that a social worker can respond directly to someone, instead of just following up later on a referral from the officers who were working a previous shift.

The National Association of Social Workers “2021 Blueprint of FederalSocial Policy Priorities” includes a recommendation to pass the Community-Based Response Act (S. 4791/H.R. 8474 in the 116th Congress) which provides a grant program that would deploy social workers as first responders instead of police.

The bodycam footage suggests that the BPD officer who did the Dec. 23 check is aware his presence as a police officer had the potential to cause the men distress: “You’re good, man. Relax. I’m just making sure you’re OK.”

The Square Beacon asked Bloomington Homeless Coalition board member Shelby “Q” Querry to comment on the question of who should respond to calls about the welfare of someone who is lying on the ground in a city park. [Querry did not comment on the bodycam footage—it was not provided to her by The Square Beacon.]

Querry said, “Whether it is an unhoused community or a person-of-color community, it’s very vital that we look at the history of what the police has done for, or did to, that community.” She added that it’s important to consider whether “there’s trust, or there’s mistrust, or there’s respect or there’s disrespect, within the relationship of the two.”

Representing BLM B-town’s core council, Jada Bee spoke to The Square Beacon about the different ways that the police deal with Black people compared to houseless people in Bloomington, which she described as a majority white community.

The police have a “hands on” approach with the Black community, Jada Bee said, but it’s different with the houseless community.

Jada Bee clarified: “When they see Black people, they go directly to them, as opposed to homeless people, they’re like,’Well, I’m gonna do the bare minimum here that’s required of me.’” It’s a matter of discretion, she said.

Jada Bee gave an example: “In the case of a young Black male, who happens to be wearing a hoodie, walking home at night, the discretion could be to assume that they want to be left alone, that they know where they’re going, and that there’s no reason to stop and talk to them.” That is not the kind of discretion the police apply, she said.

“The discretion is to stop them, question them, see if they fit the description of any crimes, check them for priors, check their ID, detain them for as long as you possibly can, and figure out some way to get them in the back of the car,” she said.

In contrast, police are generally willing to leave houseless people alone, Jada Bee said. “With homeless people, the goal is to completely ignore them, to completely marginalize them—until it’s time to physically remove them from spaces where they’re ‘not allowed to be.’”

People who are sleeping in the parks get harassed by the police out of sleeping space when the parks are cleared, but when they’re actually in need, like Vanderburg was, their welfare is not taken into account, Jada Bee said. “So either way you slice it, nobody’s welfare is being taken into account,” Jada Bee said.

Comparing the police reaction to the houseless community and the Black community, Jada Bee said, “The reactions may be different, but the outcome is the same, which is that people’s actual welfare is not ever the primary concern.”

Jada Bee wrapped up BLM B-town’s perspective on the proper role of police towards the Black community and the houseless community: “One, leave the Black people alone to enjoy themselves. Two, let people sleep in a park, if that’s what they need to do. Three, get those people who are in unsafe situations, checked out and checked on in a proper and appropriate and thorough way, so that they don’t die in 20-degree weather.”

Bodycam footage

For readers who decide to view the bodycam footage of the welfare checks done on Vanderburg shortly before he was found deceased, the link below provides access to a folder containing two video files.

For readers who are weighing whether to view it, Bloomington Homeless Coalition board member Marc Teller said about the footage: “This was tough to watch.”

Comments ()