Climate scientist on last weekend’s Bloomington rain: “It’s not like this was an absolute fluke…”

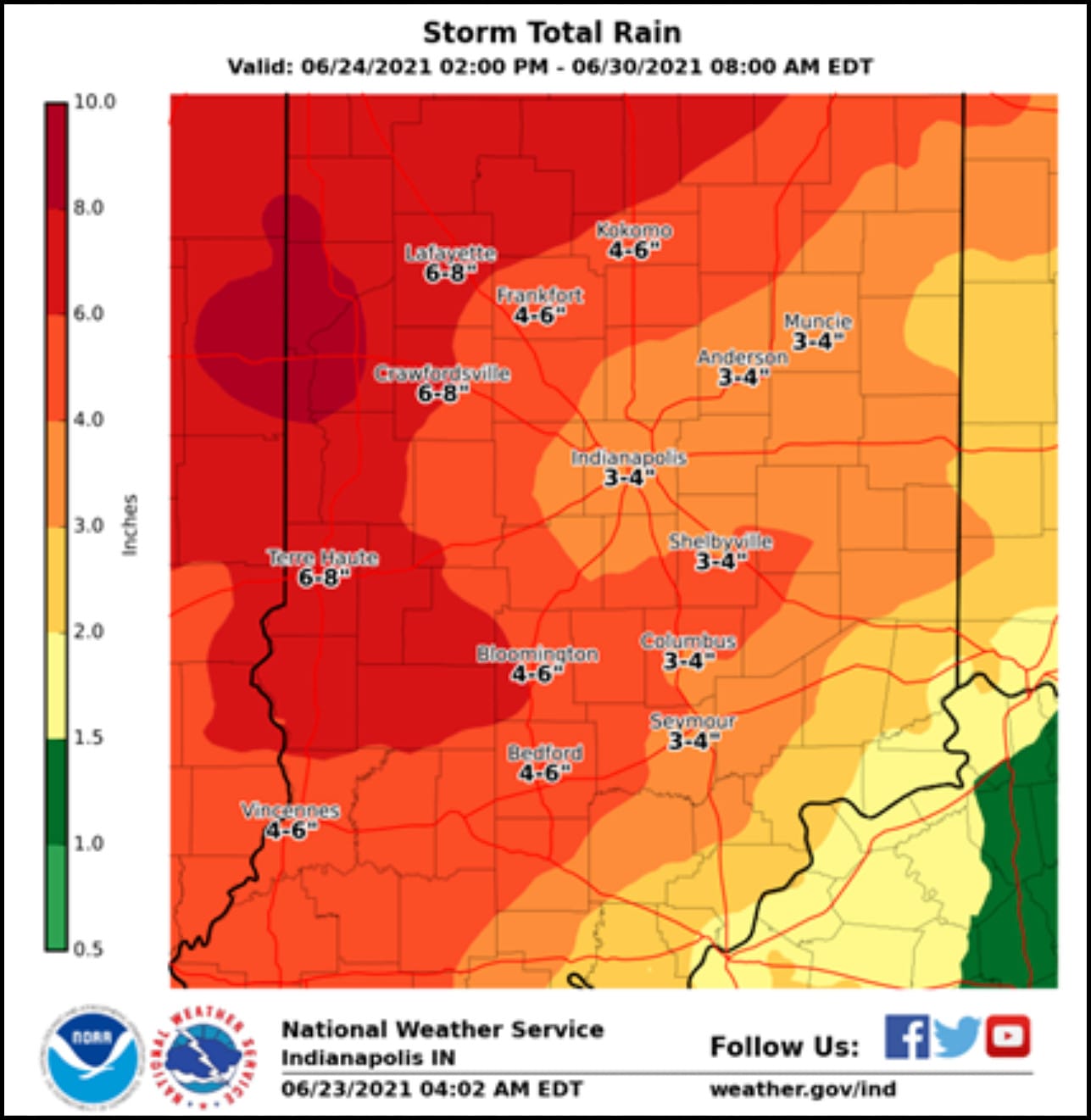

As of Wednesday, the National Weather Service is predicting 4 to 6 inches more rain for Bloomington, from Friday afternoon through Tuesday evening.

That follows 5 to 7 inches of rain that fell over a shorter period last weekend, which flooded a downtown Bloomington street, overtopped a county bridge with debris, and caused the floodwaters to sweep up one car, leaving its driver dead.

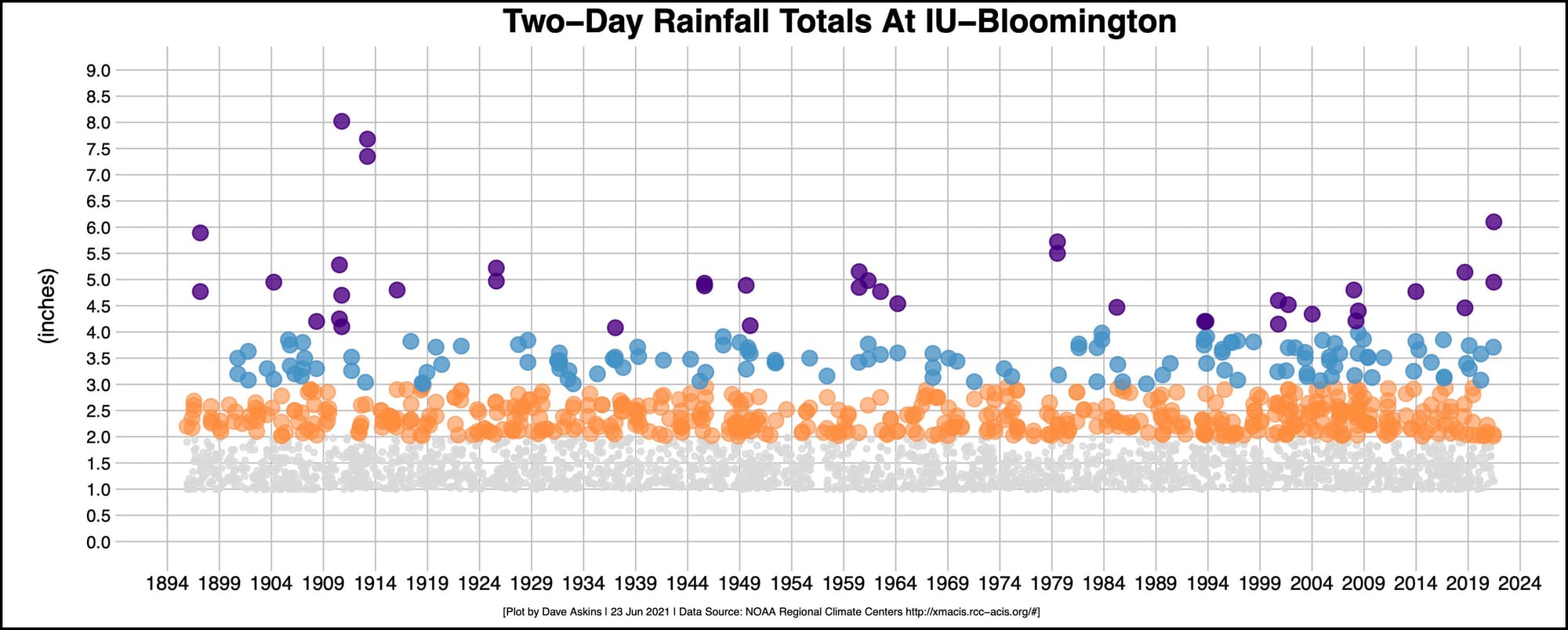

Based on the daily rainfall data in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Regional Climate Center database, last weekend’s two-day total rainfall of 6.1 inches, recorded by the Indiana University campus rain gauge, ranks it the third-worst storm, since daily rainfall totals have been kept, which starts in 1895.

The 6.1 inches measured on IU’s campus was the highest two-day total in the last century.

Does last weekend’s single event prove the case for climate change?

When The B Square spoke on Wednesday with Gabriel Filippelli, professor of earth sciences at IUPUI, he said, “Each given intense rainfall event does not mean that climate change has descended on us.”

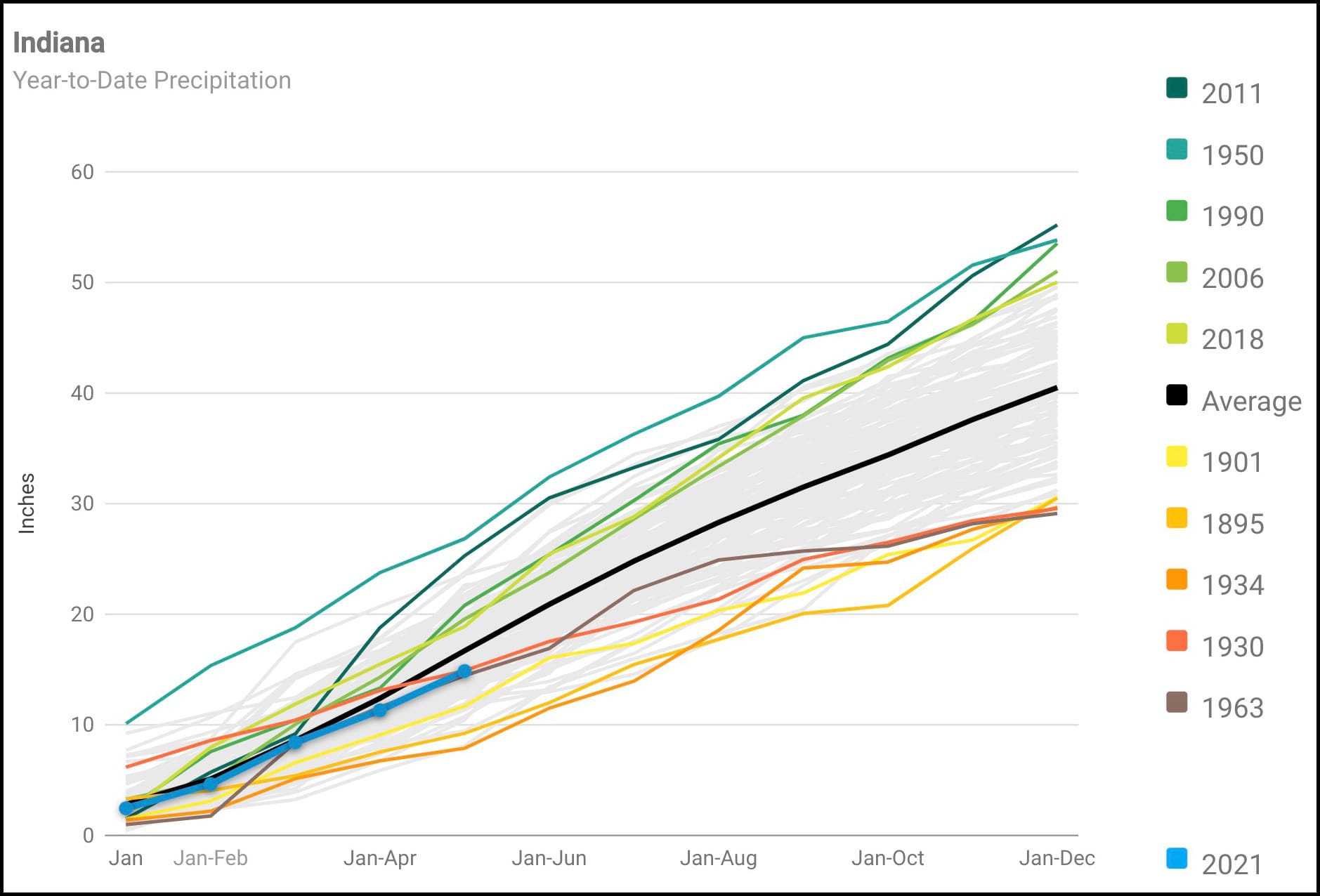

Filippelli continued, “However, when you look at the regional records and you see the number of days Indiana has had extreme rainfall events, it has gone up substantially from about the end of the 1980s on.”

The amount of extreme rainfall in central Indiana has gone up by about 15 percent since 1990, Filippelli said. He continued, “The projections are, it’s going to go up another 15 percent by 2050.”

That means extreme rainfall will continue to be likely in this area, he said. He added, “Whether climate change will make them worse or not, it’s hard to say, ”

In the context of a 15-percent increase in extreme rainfall, Filippelli assessed last weekend’s storm like this: “You know, 15 percent isn’t a lot, but it’s not like this was an absolute fluke that we’ll never see again.”

Filippelli is director of IU’s Environmental Resilience Institute. Colleagues of Filippelli’s—Travis O’Brien, who is assistant professor at IU’s atmospheric science department, and Scott Robeson, who is an IU professor of geography and statistics—have distributed an explainer on last weekend’s Bloomington storm.

The information sheet cautions against against asking the question: Did climate change cause this event?

An alternate question is encouraged: Have we observed changes in extreme rainfall like this?

That answer looks like it’s yes. According to O’Brien and Robeson’s explainer, an “extreme” amount of precipitation in Bloomington is about 1 inch in a day. Extreme precipitation in Indiana overall has “increased substantially since 1900.”

During the early and middle 20th century, the information sheet says, Indiana would see between one and three extreme rainfalls a year. Now, the state gets as many as eight per year.

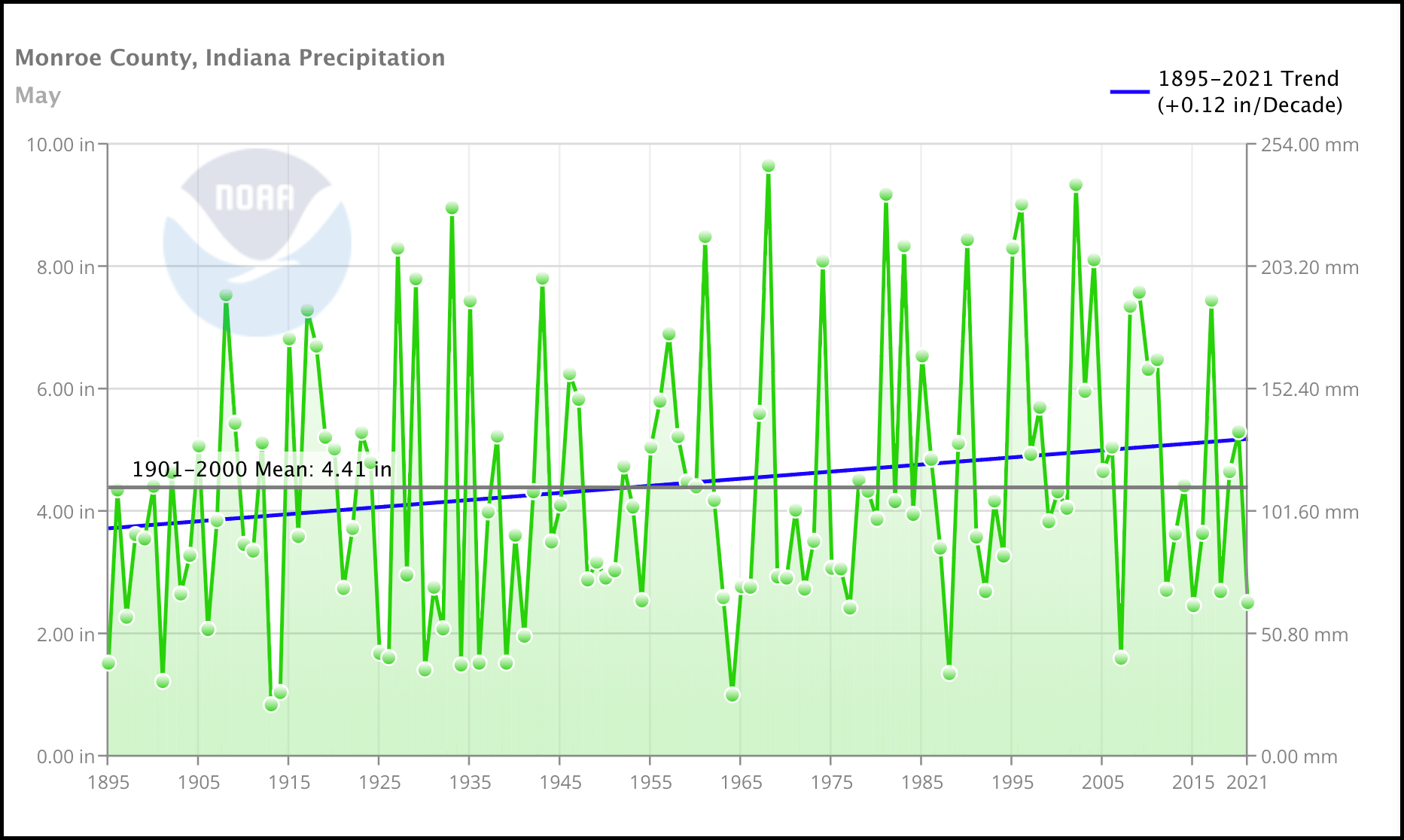

Numbers from the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information indicate that monthly rainfall totals in Monroe County, Indiana have increased about 0.12 inches per decade from 1896 to 2021.

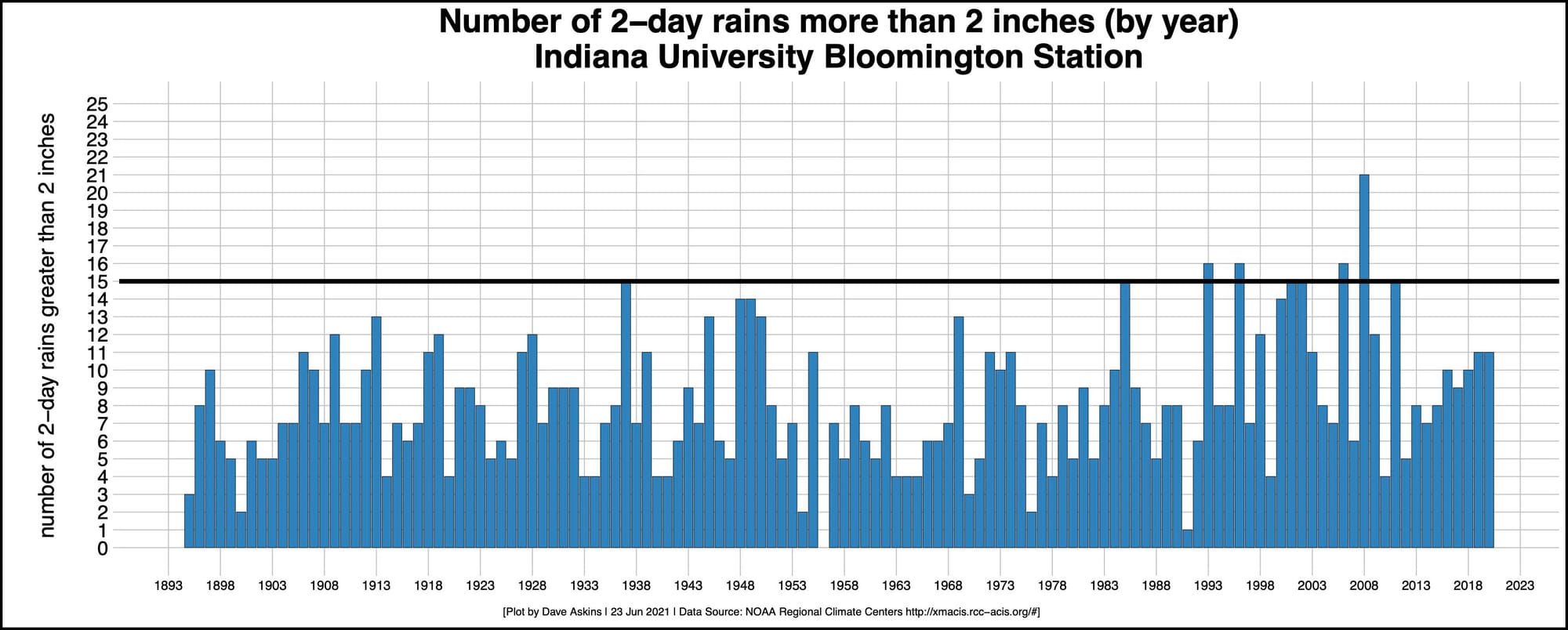

The number of 2-day rains totaling 2 inches or more for the Indiana University rain gauge looks like it’s trending upward. For each year since 1895, The B Square plotted NOAA Regional Climate Center data for the number of 2-day rains totaling at least 2 inches. Since 1993, Bloomington has seen four years with more than 15 two-day-2-inch rain events.

Before 1993, Bloomington had no such years.

Part of Filippelli’s research focuses on urban health. If a rainfall like last weekend’s was not a fluke, what does that mean for the city of Bloomington?

“Where I think climate change has to really come into play is in how municipalities deal with things in the future,” he said.

If last weekend’s rain were inconsistent with the climate projections, it would not make sense to invest a tremendous amount of money and resources and infrastructure to divert the water if it were not likely to happen very often. “But it is likely to happen more often,” Filippelli said, and that trend has “dialed up a notch” over the last 40 years.

Part of the infrastructure picture for downtown Bloomington is the underground culvert runs from Dunn Meadow at Indiana Avenue to 1st Street and College Avenue, where the waterway re-emerges above ground. It’s the culvert that is supposed to take on the water from the Kirkwood area, which was flooded last weekend.

Its middle section is currently undergoing renovation and expansion as part of the $13-million Hidden River project.

At a meeting in People’s Park on Monday morning , city of Bloomington utilities (CBU) director Vic Kelson told a gathering of business owners, who had seen their businesses flooded, that the Hidden River project had not blocked or restricted the flow during the weekend rains.

At the utilities services board meeting on Wednesday afternoon, board members were told by CBU staff that the middle section of the culvert is being expanded by the Hidden River project, because it is “still a bit undersized.”

One of the challenges faced by an approach to stormwater management involving an underground culvert is that once the size is fixed, it requires major construction and millions of dollars to expand.

In the language of the Environmental Resilience Institute, an underground culvert by itself provides “weak resilience.” Filippelli put it like this: “It’s a fixed volume. And where you fix the volume is often dependent on certain assumptions, maybe past rainfall events, that may not be true in the future.”

What’s the alternative? As Filippelli described the challenge, it’s not so much an alternative as an augmentation. He said, “To develop something called strong resilience, you just need to add to that.” In the case of Bloomington’s underground culvert, that would mean near the entry point to the culvert, at Indiana Avenue and 6th Street, installing large retention swales—rain gardens.

Filippelli’s description of strong resilience in that context sounded similar to a question that CBU director Vic Kelson was asked on Monday morning at the People’s Park meeting. He was describing a future project that would enlarge the culvert inlet at 6th Street and Indiana. Is Dunn Meadow being considered as a detention pond in connection with that project?

Kelson indicated that the inlet would be made bigger so that it could accept the water coming off Dunn Meadow. But Dunn Meadow is not being considered as a detention pond, Kelson said.

Filippelli wrapped up his remarks to the B Square by saying when he talks to people about climate change, and the adding of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels, “I’m not an alarmist. I am a realist.”

As a geologist, he said, he could say basically almost all past changes in the earth’s climate have been driven by variations in our greenhouse gas concentrations—carbon dioxide mostly.

“The geologic record underneath your very feet is dominated by this history of carbon dioxide,” he said, adding, “It shouldn’t be any surprise that when we add more of it, it changes climate.”

Two-Day Totals for IU Campus Rain Gauge

| RANK | Date | Two-Day Total |

| 1 | 1910-10-06 | 8.02 |

| 2 | 1913-03-26 | 7.68 |

| 2 | 1913-03-25 | 7.35 |

| 3 | 2021-06-20 | 6.1 |

| 4 | 1897-03-05 | 5.89 |

| 5 | 1979-07-14 | 5.72 |

| 6 | 1979-07-13 | 5.5 |

| 7 | 1910-07-17 | 5.28 |

| 8 | 1925-08-13 | 5.22 |

| 9 | 1960-06-24 | 5.15 |

| 10 | 2018-09-09 | 5.14 |

Comments ()