Concern about Bloomington’s police staffing levels in light of potential annexations: By the numbers

According to Bloomington’s fiscal plan in support of its proposed annexation of territory, the police department would need to add between 24 and 31 sworn officers, at a cost of up to around $2.6 million a year.

The additional officers would be needed in order to provide service to 9,000 more acres of area, and about 14,000 more people, based on Bloomington’s annexation plans.

At Wednesday’s public hearing on the proposed annexations, the president of Bloomington’s police union spoke about his concerns.

Paul Post, who’s president of the Fraternal Order of Police, Lodge 88 and a senior police officer for BPD, asked the city council: “Will the city have enough police officers to provide basic police services for the new version of Bloomington?”

It’s an open question, according to Post, because BPD has not been able to maintain the number of officers authorized in the city’s current budget.

BPD has fewer sworn officers than its budgeted number, but is losing officers as fast as the department can replace them, based on Post’s description.

The immediate consequence of the officer shortage, according to Post, is that all three of BPD’s uniformed patrol shifts have had to lower their daily minimum staffing levels. BPD is working at or below minimum staffing, Post said.

That means there are fewer officers who are available to field increased calls for service like “weapons in progress,” according to Post.

The numbers in Bloomington’s online payroll system and calls for service dataset basically square up with Post’s remarks.

BPD staffing levels

A year ago, Bloomington’s police department had 10 fewer officers than it was supposed to, based on the numbers in police chief Mike Diekhoff’s budget memo to the city council. The 2020 budget for BPD called for 105 sworn officers, compared to the 95 who were serving the city at the time.

The proposed 2021 budget dropped the number of sworn officers to 100, replacing the five sworn positions with a mix of social workers and neighborhood resource officers. A largely symbolic resolution of the city council, passed in connection with the 2021 budget, stated that the authorized number of sworn officers was 105, but provided no money in the budget for them.

An outside consultant’s report, released last year, recommended adding as many as 16 officers to the 105 that were budgeted at the time, which would have translated into 121 officers.

Using 121 sworn officers as a benchmark, and adding another 31 officers to account for annexation, would leave BPD with about 50 officers fewer than called for in the consultants report, combined with the annexation fiscal plan.

At Wednesday’s public hearing, Post said that hiring 50 more officers without losing any to resignations or retirements in the next three years is “a nearly impossible goal.”

Based on data extracted by The B Square from the city’s online financial system, 96 officers—including the chief and deputy chief, and 7 officers who started after mid-May—were on the payroll for the most recent bi-weekly period.

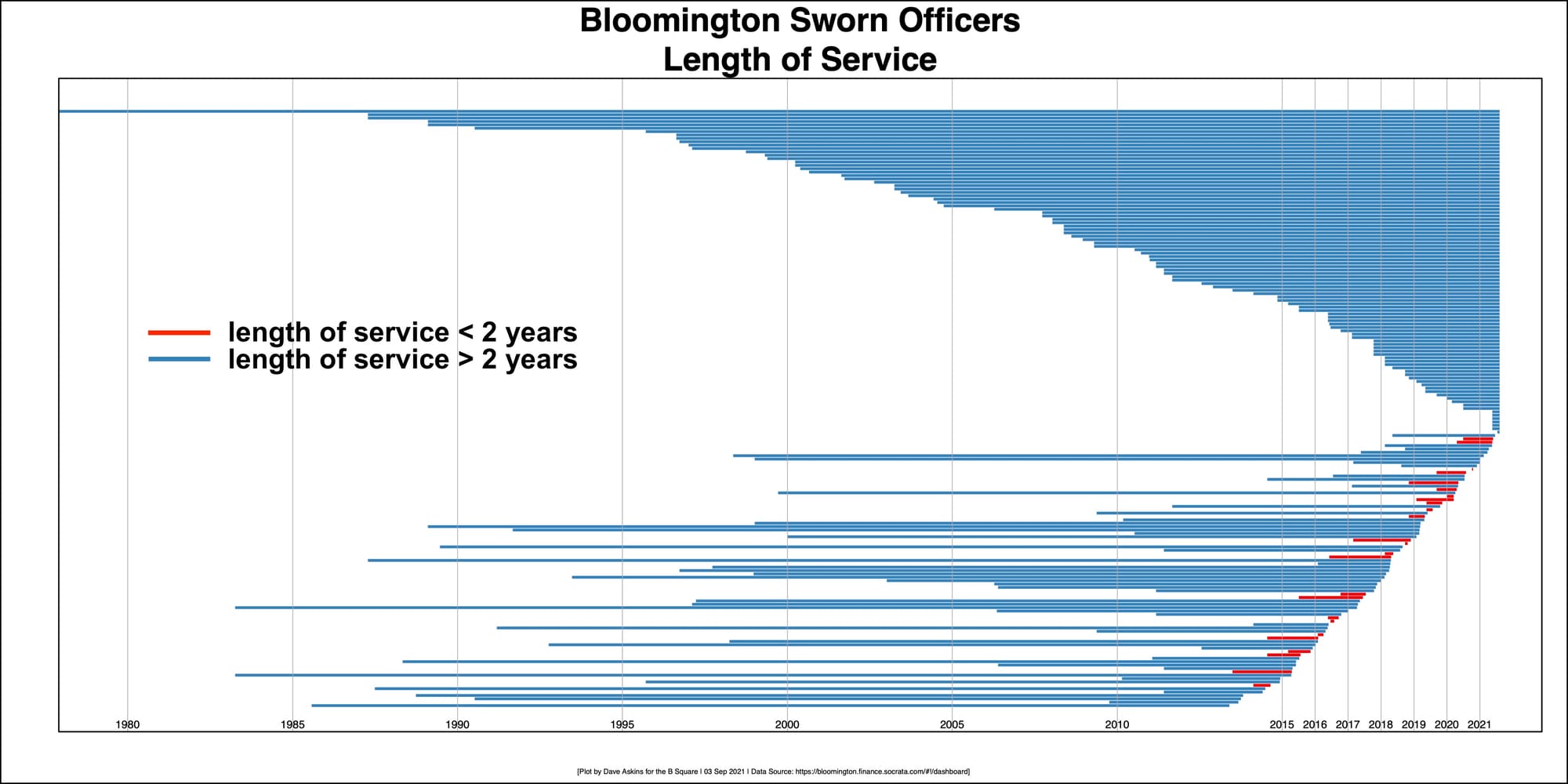

Post said that during Bloomington mayor John Hamilton’s service, BPD has hired 65 officers, but 67 had left the department during the same time period. That translates into a loss of training dollars and institutional knowledge, Post said.

Based on the payroll data extracted from the city’s system, it looks like much of BPD’s challenge in retaining officers has come among the most recently hired.

Of the 64 officers in the system with start dates after Hamilton took office on Jan. 1, 2016, 28 of them (44 percent) already have end dates for their service.

Those who left BPD between 2013 and 2016 had on average (median) nearly 7 years of service, compared to an average (median) of 4 years of service for those who have left BPD after 2016.

That turnover trend does not yet seem to have translated into fewer years of service on average among BPD officers. Based on payroll data, BPD’s 96 current sworn officers have a median of 10.19 years with BPD. In 2013, the 98 sworn officers on the payroll had served BPD for a median of 9.88 years.

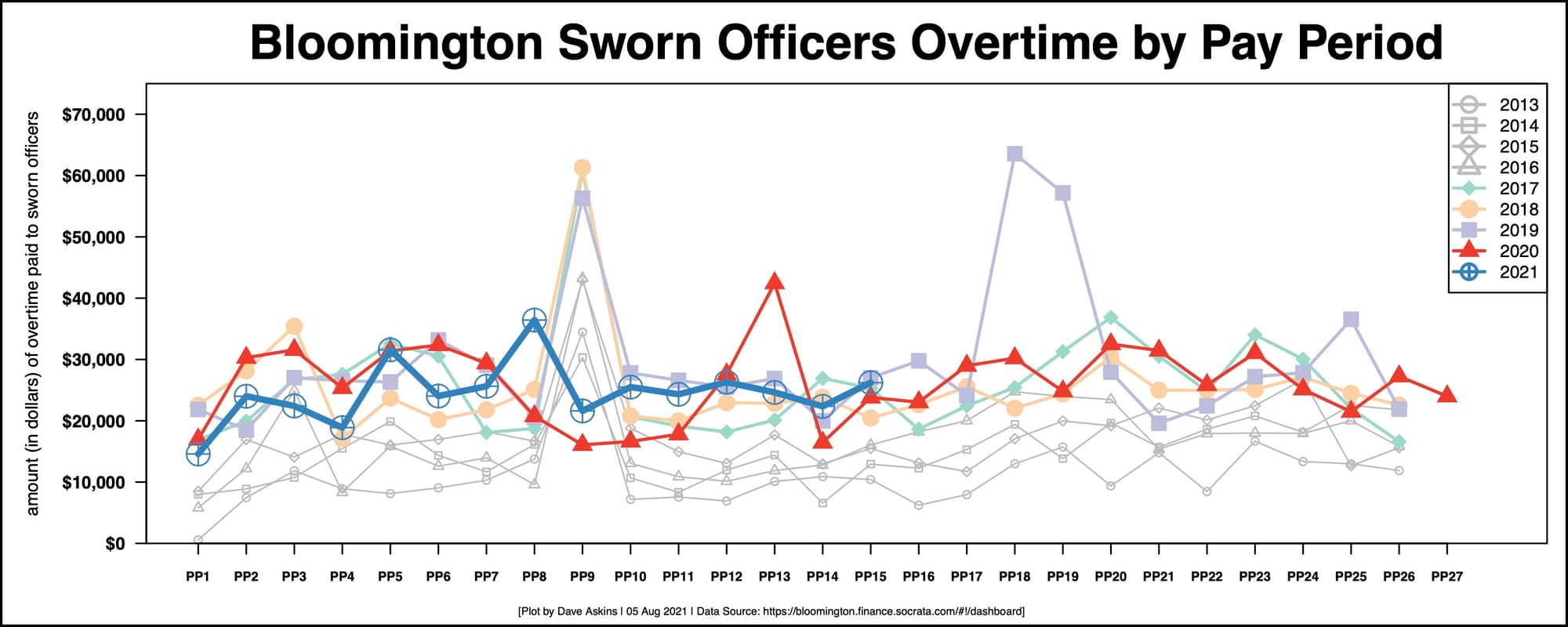

Overtime staffing

One of the issues described by Post during Wednesday’s public hearing was the mandatory extra time that officers now have to work, in order to cover some of the regular shifts.

The payroll dollar figures for overtime show that for this year, the amounts paid out for overtime have been, from period to period, about as high as they’ve ever been. But this year has not included the spikes of the last two years.

The weekend of Little 500 typically generates an overtime spike in late April. Due to the pandemic, last year and this year, a Little 500 spike isn’t reflected.

An overtime increase in June 2020 was connected to nightly Black Lives Matter demonstrations that often took to the streets. An overtime increase in August 2019 was connected to protests at the city’s farmers market.

The amount of overtime is not a perfect measure of the extra time that officers are required to work, Post indicated in an email to The B Square. If an officer is being held over from their regular shift to cover another shift, they can take that in comp hours, Post wrote.

Post added, “I’m not sure if the city has done a cost/benefit analysis to compare overtime/comp time vs. actually hiring enough officers.”

The overtime figures for this year are affected by the willingness of officers to sign up for voluntary overtime slots, according to BPD detective Jeff Rodgers, who is a shift representative for the union.

In an email to The B Square, Rodgers wrote that because regular shifts are short-handed, officers are not allowed to take days off. And because officers are “burnt out” both mentally and physically, they are not willing to sign up for voluntary overtime.

In years past, the voluntary overtime slots for the “Downtown Patrol” have been completely filled, Rodgers wrote. But this year, there were 40 unfilled overtime slots in June and 51 unfilled slots in July.

Just the empty voluntary overtime slots for “Downtown Patrol,” would have generated an overtime payment of $13,104 for June and July, Rodgers wrote.

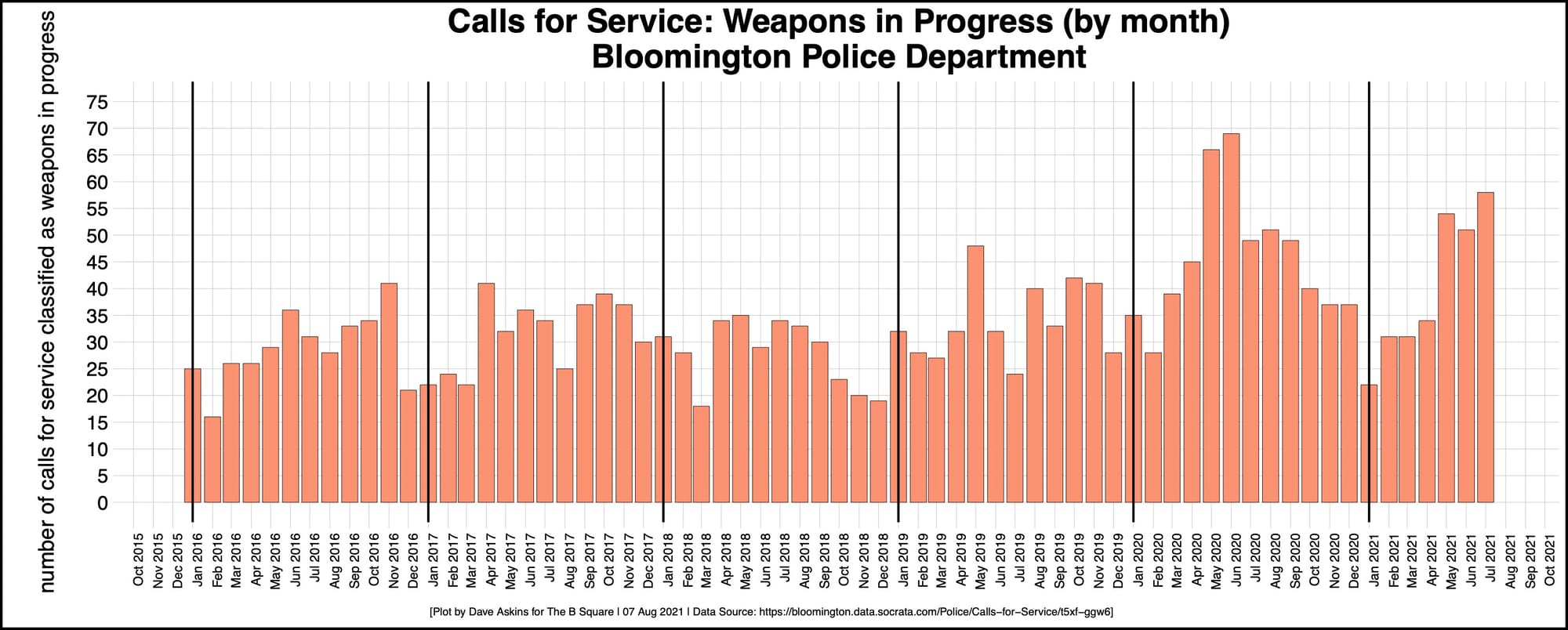

Weapons, mental health calls

At Wednesday’s public hearing, Post said staffing levels were dropping while calls about violent crimes have risen. As an example, he gave “weapons in progress” calls. Since June 1 there have been 129 such calls, including three stabbings in July, and six shootings in the past two weeks, Post said.

Responding to an emailed question from The B Square, Post said a “weapons in progress” call can involve any form of weapon—a gun, knife, bat, pick axe, etc.

Based on Bloomington’s calls for service dataset for BPD, the number of “weapons in progress” calls has increased for the last two years.

For the four pre-pandemic years from 2016 through 2019, the monthly average number of “weapons in progress” calls for May, June and July was in the low to mid 30s (32, 34, 33, 35). Last year, the monthly average during the same three-month period nearly doubled, to 61 calls. This year, the number was 54—not as high as last year, but still clearly higher than pre-pandemic years.

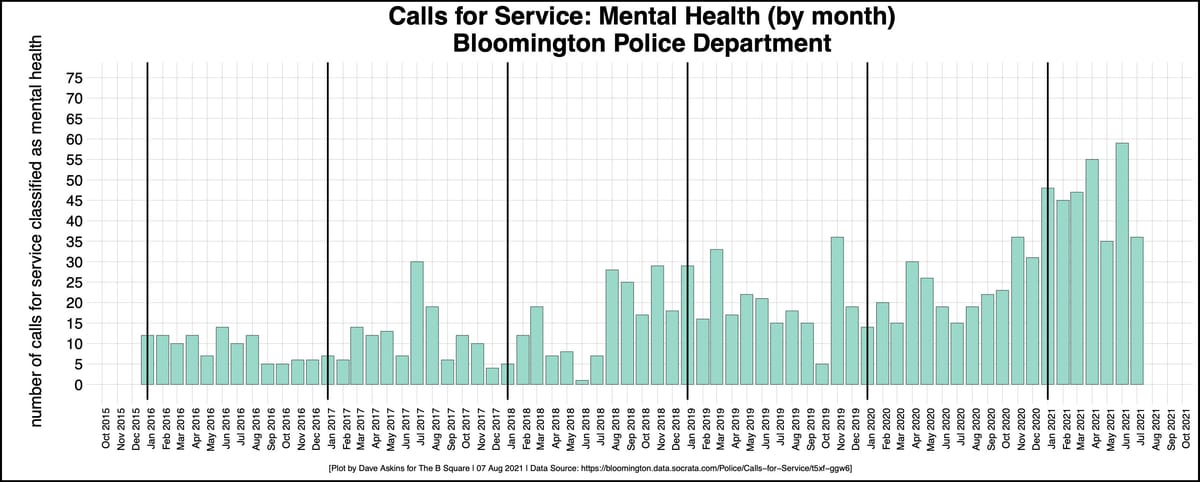

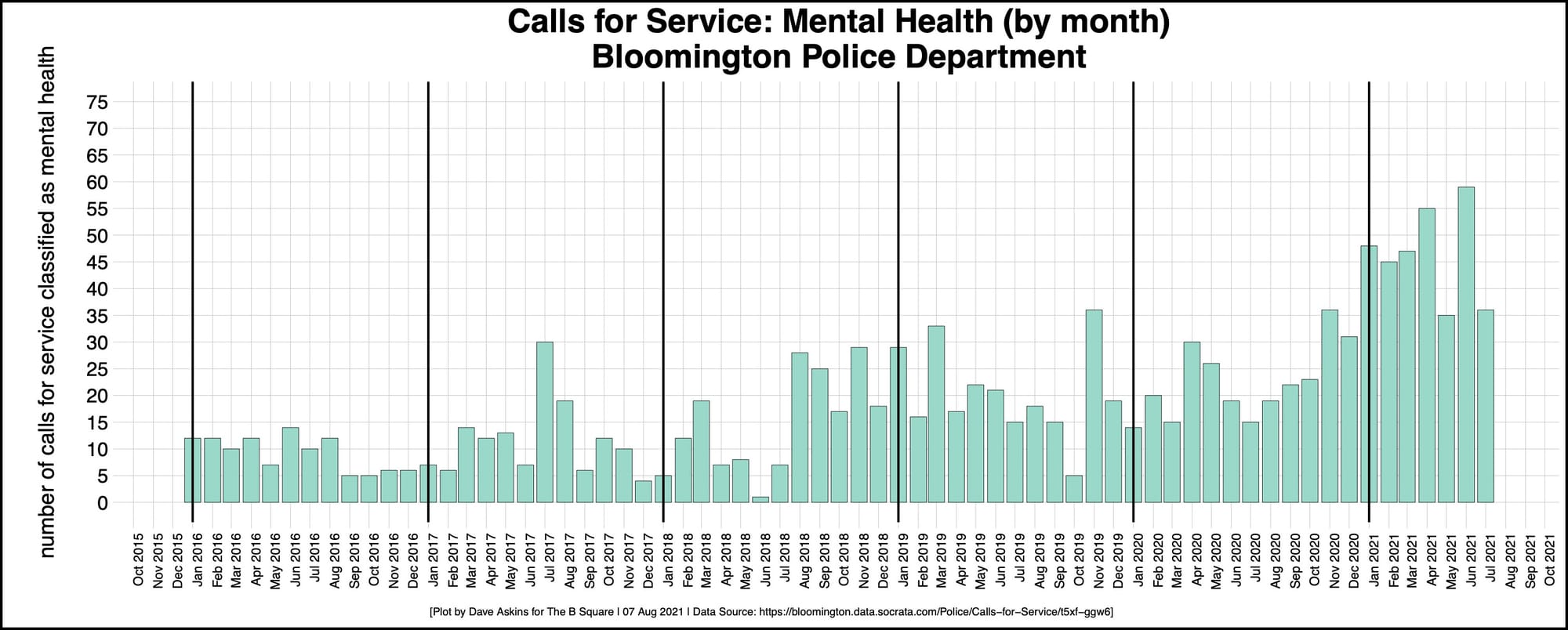

Another type of call for service that has seen an increase is “mental health” calls. Grouping all such calls (in-progress and not-in-progress) as a single category shows a nearly three-fold increase—from November 2020 through the end of July this year, compared to the period between January 2016 and October 2020.

According to Post, such calls can include range of situations—actual suicide attempts, a family member who shared a suicidal ideation, or a person “talking out of their head” and walking around downtown.

In response to an emailed question from The B Square, dispatch manager Amy Hensley, wrote that the protocols have not changed for the way such calls are marked: “We mark it mental health if the caller specifically tells us it is, or if the officer on scene tells us it is,” Hensley said.

About the increase in “mental health” calls for service, Post wrote, “This is somewhat reflected in the concept of sending law enforcement to everything.” He continued, “[It] oftentimes places the officers in situations that may not necessarily require a police response.”

Post put the issue in the context of the national discussion on policing over the last two years. He wrote, ”[L]aw enforcement is placed in situations sometimes that could be better handled if directed to ambulance service, mental health counselor, etc. This will require having those other resources available.”

Post added that it would require that calls be triaged from the time of the initial 911 call to get the appropriate response.

Comments ()