3 OKs in 3 days: Bloomington gets needed nods for high-speed internet fiber deal with Meridiam

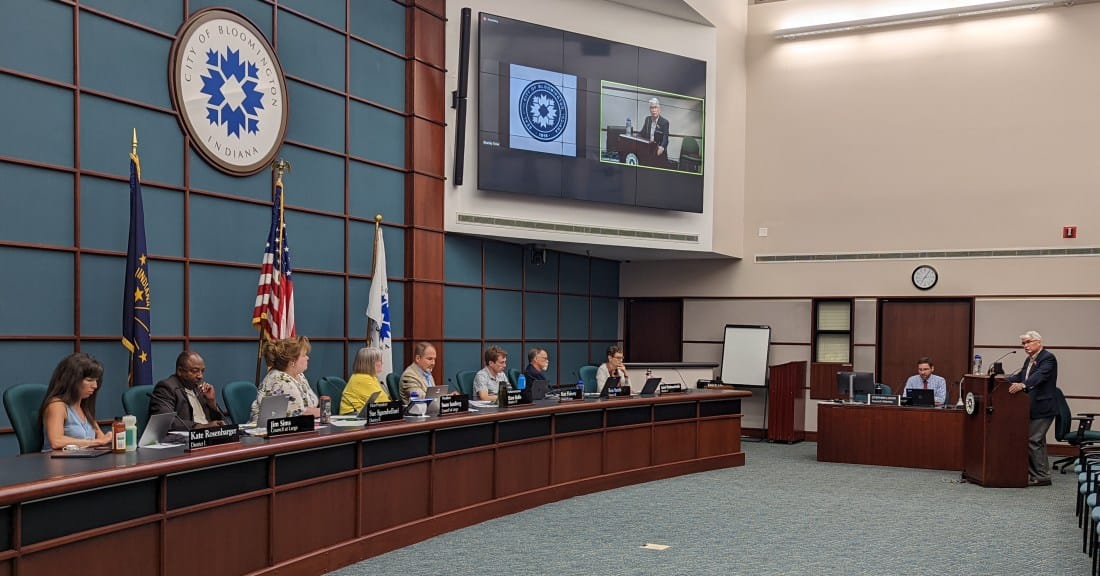

At its Wednesday meeting, Bloomington’s city council took a couple of steps, on 8–1 votes, as a part of a potential deal to get high-speed internet connections built for most of the city.

The pending agreement would be inked between Paris-based Meridiam and Bloomington.

Under the arrangement, Meridiam would construct a fiber-to-the-home open-access network offering symmetric 1-Gigabit service. Meridiam would offer symmetric 250-Megabit service to low-income residents at zero net cost.

The arrangement would add another competitor to Bloomington’s market by giving an as-yet-unnamed internet service provider (ISP) exclusive access to the new network for at least five years. The initial ISP would also have exclusive access to the roughly 17 miles of conduit and fiber—the Bloomington Digital Underground—which has already been constructed by the city.

The agreement has been analyzed by the Indiana Cable & Broadband Association as “unfairly favoring one provider over others,” which ICBA says conflicts with the federal Telecommunications Act of 1996. ICBA’s legal objections got no mention during deliberations by Bloomington public officials this week.

Wednesday was the third day in a row that three different public bodies took required steps for the deal to go through. All of the votes were unanimous except for those by the city council.

Dave Rollo was the sole dissenting voice in the whole mix. Rollo asked several questions about the possibility that Bloomington could create a municipally-owned utility for a fiber-based internet service—instead of pursuing a model where ownership control goes to a private entity. Rollo questioned whether the public-utility model had been given adequate consideration.

Rollo also questioned the required coverage commitment of just 85 percent of the city that is recorded in the pending agreement .

On Monday, the city’s plan commission found the deal to be consistent with the city’s comprehensive plan.

On Tuesday, the city’s economic development commission approved an expenditure agreement that, among other things, green-lighted an expenditure agreement that reimburses to Meridiam 95 percent of the roughly $10.9 million in personal property taxes that Meridiam will pay over a 20-year period. The legal tool that’s to be used is a tax increment finance (TIF) area.

On Wednesday, the city council approved the expenditure agreement, like the EDC did. In a separate vote, the city council approved and issued the finding of the Bloomington plan commission.

What kicked off the three-day flurry of action was a vote by Bloomington’s redevelopment commission (RDC) in the first week of June, to pass a declaratory resolution for an economic development area, designating it as a TIF (tax increment finance) area, and approving an economic development plan.

It’s the RDC that will bookend the process, with a confirmatory resolution that is set for a vote on July 5.

The recent activity related to a fiber-to-the-home network follows an announcement in November last year that a letter of intent had been signed between Bloomington and Meridiam. But that stemmed from a request for information (RFI) that was issued much earlier by the city, in 2016. That’s the year John Hamilton took office, having been first elected in 2015.

A report by the Herald-Times at the time described Hamilton’s intent to create a “community-owned, city-wide fiber internet network.” The issuance of an RFI to potential private partners reflected somewhat of a departure from the idea that the fiber internet network would be “community-owned.”

On Wednesday, Rollo’s question about a publicly-owned model drew a two-part answer from Bloomington IT director Rick Dietz. First, those municipalities that have undertaken construction of their own fiber internet systems generally operate their own electric utilities.

One example is Palo Alto, California, which is Bloomington’s “sibling city.” Another example, closer to home, is Richmond, Indiana.

Bloomington does not operate its own electric utility.

A municipality that operates its own electric utility also controls the utility poles. That means it does not need to negotiate with a separate electric company to string fiber between poles, in places where installing conduit underground is not feasible.

A second part of the answer Dietz gave was based on the politics of the state of Indiana. Dietz said he thinks if Bloomington were to pursue a municipally-owned model for internet fiber, the General Assembly would kill the project.

Another challenge that the city would need to meet is the capital investment required to install the network. Meridiam says it’s putting $50 million into the project. Rollo indicated he thinks an incremental approach, possibly slower than the three-year build-out that Meridiam has planned, could be workable if Bloomington pursued a municipally-owned model.

Rollo pointed to the 35-percent target for the initial, exclusive ISP’s market share, and used it as the basis of some “back of the napkin” calculations. Rollo said that’s about 14,000 dwellings, and if they each pay $80 in fees a month, over 20 years, that’s around $300 million. It’s a very “lucrative” proposition, Rollo said.

Rollo said, “This presents essentially a tremendous revenue stream that we are not pursuing.” Rollo wanted to know if a cost-benefit analysis of the public option had been done. Dietz told Rollo such an analysis had been done and that the public option was very “risky”—because Bloomington does not own its own electric utility and because of the political climate in Indiana.

Another point pressed by Rollo on Wednesday was that, under the draft agreement, Meridiam has to provide coverage to 85-percent of the city, not 100 percent. Rollo noted that a representative from Comcast had indicated that they reach 98 percent of the city. Rollo wanted to know: Why doesn’t the city demand that Meridiam provide coverage to more than 85 percent?

Dietz responded by saying the city was able to require Comcast to provide complete coverage under a franchise agreement—but such franchise agreements are no longer legally possible.

Rollo followed up by saying about the 85 percent: “I feel it is insufficient. It doesn’t meet my idea of equity. It’s not internet for all.” Rollo added, that if Comcast was able to overcome whatever obstacles exist for extending service everywhere, the same should be asked of Meridiam.

On Wednesday, other councilmembers were satisfied that the public option was not feasible. They were also satisfied that 85-percent coverage was a high enough number for the written agreement, given that Meridiam’s representative indicated an intent to achieve better than 85-percent coverage.

Another point that appeared to be persuasive for councilmembers is the $85,000 annual contribution that Meridiam has to make to the city’s digital equity fund, under the terms of the agreement. That money will likely go towards ensuring that lower-income households have adequate devices to take advantage of a high-speed fiber connection and training on the use of the equipment.

If all goes as planned, construction of the new network will begin later this year and the first customers will be connected be connected before the end of the year.

Comments ()