Denied by Bloomington: Request to vacate two strips of right-of-way where parts of buildings stand

If a property owner asks the city of Bloomington to give up some public-right-of-way, the city’s default answer is no.

On Wednesday, Bloomington’s city council hewed to that basic standard, when eight of nine councilmembers voted against Solomon Lowenstein’s request for vacation of two strips of land.

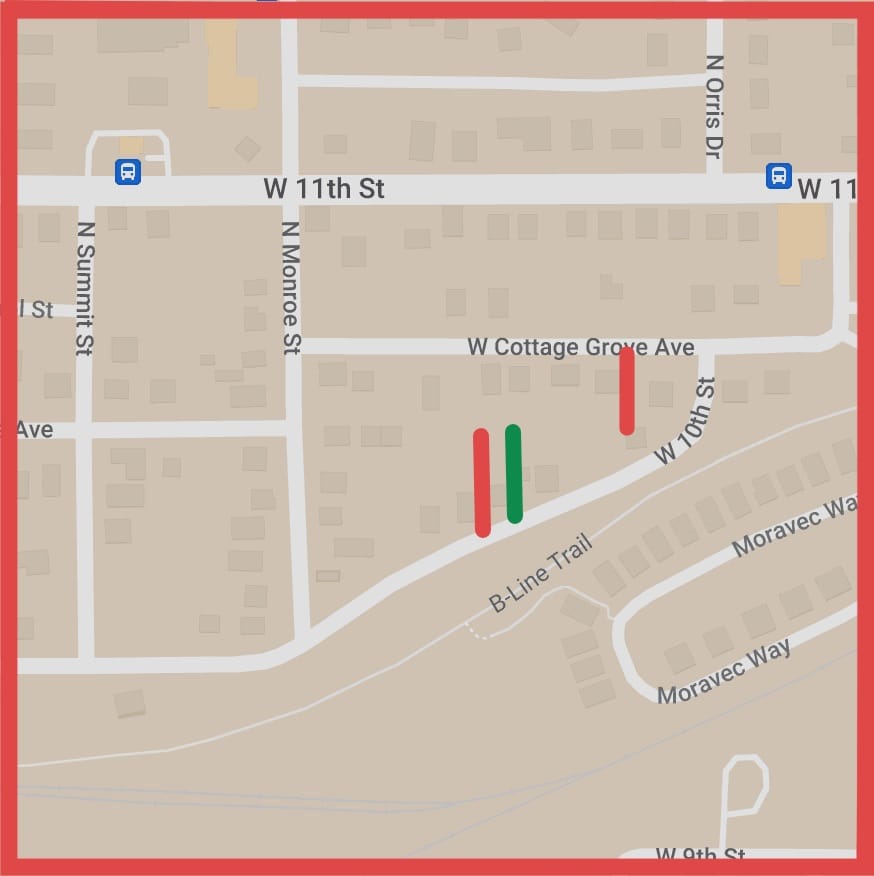

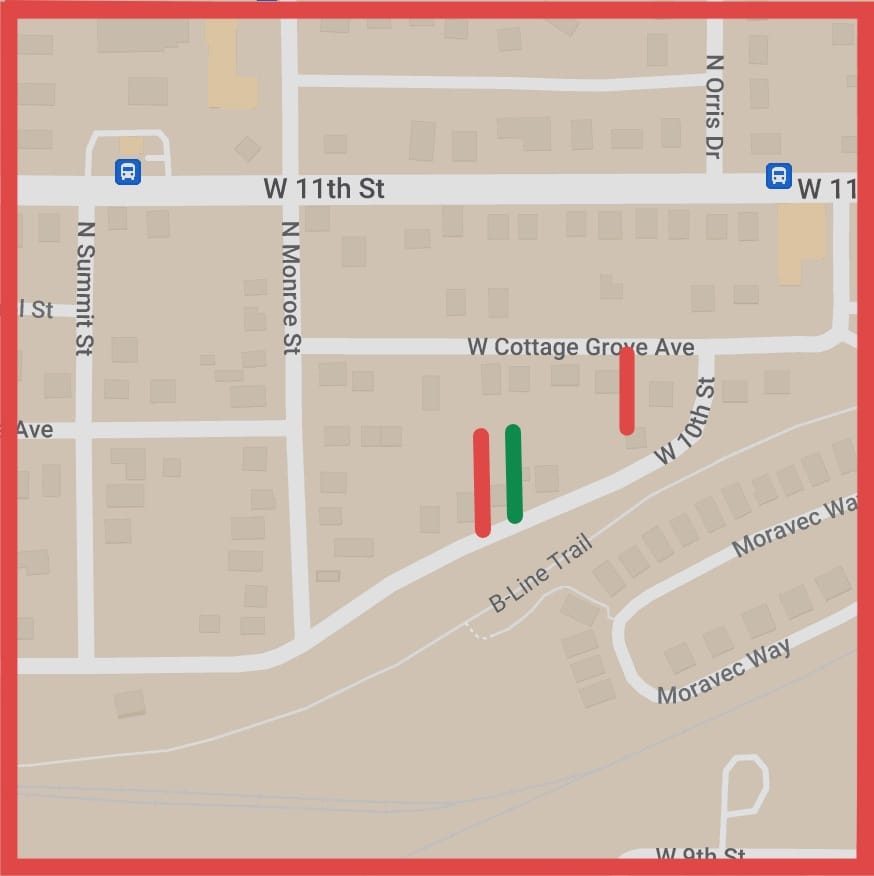

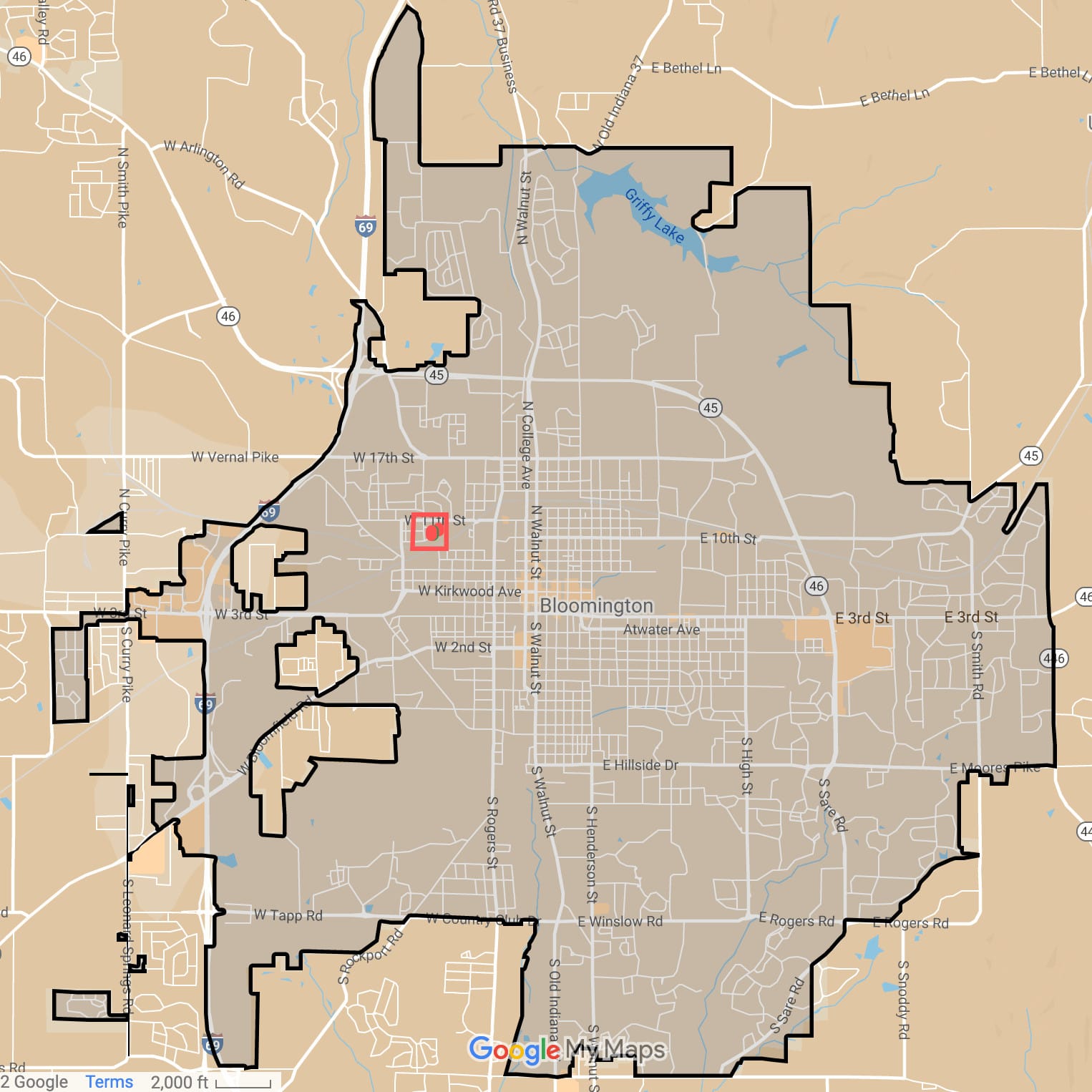

The property is in the northeast part of the city, just south of 11th Street near the B-Line Trail.

The proposal got just one vote of support, from Ron Smith.

The historical background goes back around 100 years. More recently, in 2014, the city council considered, but ultimately denied ,a package of vacation requests, that also included Lowenstein’s. The vote eight years ago was 3–4, with two councilmembers absent—Steve Volan and Dave Rollo.

Why did Lowenstein, then as now, want the city to give up some land that is owned by the public?

Some of the context includes the fact that Lowenstein owns more than one parcel on the block. They’re relatively small houses, one of them around 1,000 square feet.

A house and a garage owned by Lowenstein actually encroach on the two strips of right-of-way—for reasons that appear to be around a hundred years old, when that part of the city was platted.

So from Lowenstein’s perspective, the fact that parts of the buildings he owns sit partly in the public right-of-way puts them in jeopardy—because the city could insist that he take down the encroaching parts of the buildings. Lowenstein says that makes him disinclined to make further investments to improve the properties.

As a kind of horse trade, in exchange for the right-of-way vacation, Lowenstein offered to grant the city an easement, so that the city of Bloomington utilities (CBU) can access the east-west running waterline that cuts across the properties.

As a practical matter, the proposed strip for an easement is the typical way CBU gets access to the water line, Lowenstein says. On Wednesday, Lowenstein’s attorney, David Ferguson showed the city council photographs in support of that position.

That is, when CBU needs to get access to the water line, CBU does not use the existing strips of public right-of-way—which are impractical due to overgrowth and the steep slope—but rather the strip that Lowenstein owns.

But the wording of that easement had not yet been worked out. Smith’s vote in favor of Lowenstein’s request reflected Smith’s perspective that with more time, Lowenstein and CBU might be able to reach agreement on the wording.

The council’s inclination not to grant the vacation was supported not just by the city’s general default position, but the objections from several different city organs to Lowenstein’s specific request.

On Wednesday, Bloomington zoning compliance planner Liz Carter ticked through the objections, which came from the city’s engineering department, city of Bloomington utilities (CBU), the board of public works, and Bloomington’s planning and transportation department.

At the council’s committee-of-the-whole meeting the week before, councilmember Jim Sims noted that the way the objections from various entities within the city had stacked up made it difficult for him to substitute his own judgment.

The objection from planning and transportation was conveyed to the city council by assistant director Beth Rosenbarger. (Councilmember Kate Rosenbarger is Beth Rosenbarger’s sister. Councilmember Matt Flaherty is Beth Rosenbarger’s husband.)

Councilmember Dave Rollo asked Beth Rosenbarger how the strips of land could actually be used by the city. Rollo phrased the question like this: “So is this just a matter of principle that we shouldn’t surrender right-of-ways? Or is there something I’m missing here in terms of the utility of the specific right-of-ways?”

Beth Rosenbarger told Rollo that platted alleys often do actually get built. As an example, she gave a redevelopment housing project at the intersection of East 12th Street and Fess Avenue, where the developer is improving the alley in order to access their property. From the city’s perspective, that is preferable to the alternative, which is to build a drive cut off 12th Street or Fess Avenue, Beth Rosenbarger said.

While Smith and councilmember Steve Volan indicated some interest in delaying to see if CBU and Lowenstein might be able to agree on the wording of the easement, Flaherty said even with agreed-upon easement wording, he would not support the right-of-way vacation.

On Wednesday, city attorney Mike Rouker weighed in with a full-throated objection to the vacation of the public right-of-way, citing an Indiana court of appeals case Sagarin v. City of Bloomington. Rouker cited the case in order to undercut any claim that the platting of the land nearly a hundred years ago to include buildings in the right-of-way followed by the city council’s decision to deny a right-of-way vacation would amount to a “taking.”

Rouker told the city council that based on Sagarin v. City of Bloomington, Lowenstein’s only “relief” in these circumstances would have been for Lowenstein to have negotiated a reduced purchase price, based on the fact that some of the structures stood in the right-of-way.

As Rouker put it, “When Mr. Lowenstein bought his properties in 2012 and 2016, he did so with the full ability to assess the relationship between the structures on that property and the alleyway and to procure the properties at a discounted value based on the relationship of those structures to the alleyway. That is his only relief.”

Rouker continued, “The fact that the structures on the property are improperly located in an alleyway is not a taking.” He added, “It wasn’t a taking when the council denied Mr. Lowenstein’s request in 2014. And there’s no taking in 2022. That’s all I have to say.”

Responding to Rouker’s argument that it would not amount to a taking for the council to deny the request for a right-of-way vacation, Lowenstein’s legal counsel David Ferguson said, “I don’t even know what the taking argument is talking about. It sounds emotional, but it’s not anything we’ve ever brought up.” Ferguson added, “I don’t even think it’s applicable.”

It was not the only occasion on Wednesday when Rouker brought up the 2014 request for a right-of-way vacation. Rouker said, “Staff, of course, also opposed the surrender of these alleys at that time in 2014.” Rouker told city councilmembers: “I know many of you were on the council at the time that that request was denied.”

In fact, of the current councilmembers, only Dave Rollo, Susan Sandberg, and Steve Volan were serving on the nine-member council in 2014. Other members that year were: Dorothy Granger; Marty Spechler; Darryl Neher; Andy Ruff; and Timothy Mayer.

When the request for an alley vacation got a vote on July 16, 2014, of the three, only Sandberg was present. Rollo and Volan were absent. Sandberg voted for vacating the alley. The meeting minutes for the council’s July 16, 2014 meeting minutes record the tally like this:

Ayes: 3 (Ruff, Sturbaum, Sandberg), Nays: 4 (Neher, Mayer, Spechler, Granger)

The 2014 request was part of a five-alley request including several other petitioners besides Lowenstein. Their 2014 petition also initially included the same east-west strip of land that was eventually withdrawn as a part of Lowenstein’s petition this time around.

The 2014 city council vote was taken on a petition that was amended by a vote of the council on July 16, 2014 to remove the east-west alley from consideration.

Even if Lowenstein’s requested vacation is now decided, still hanging in the balance for the city council is a request for an alley vacation from Peerless Development on the downtown parcel where the Johnson’s Creamery smokestack has now been partially demolished.

In July, the council tabled the Peerless Development request for an alley vacation. Possibly in the works is some arrangement that would effectively move the existing alley a bit to the south.

Comments ()