March 15: Oral arguments on Bloomington’s constitutional challenge to 2019 annexation law

Next Friday (March 15) at 8:30 a.m., oral arguments will be heard on Bloomington’s constitutional challenge to a state law about annexation waivers.

It’s part of a long court process to determine how big Bloomington will be in the next few years.

The hearing will take place in Monroe County circuit court at 7th Street and College Avenue.

The state law in question was enacted in 2019. It caused annexation remonstrance waivers to expire, if they were more than 15 years old.

A remonstrance waiver is a document that some landowners signed, agreeing to give up the right to remonstrate against annexation into the city, in exchange for connection to the city sewer system.

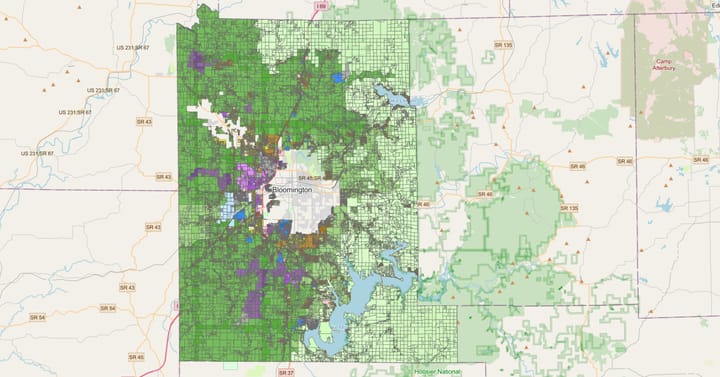

At least on the surface, Friday’s hearing on the constitutional question involves just five of the seven areas (Area 1C, Area 2, Area 3, Area 4, and Area 5) for which Bloomington’s city council passed annexation ordinances in 2021.

But a legal thicket involving the other two areas (Area 1A and Area 1B) could have an impact on the way the constitutional case is decided.

What is the constitutional question?

Bloomington claims that the 2019 law, which voids remonstrance waivers that are more than 15 years old, violates Indiana’s constitution, as well as the U.S. Constitution.

Article I, Section 24 of Indiana’s state constitution reads: “No ex post facto law, or law impairing the obligation of contracts, shall ever be passed.”

And Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution states, “No state shall … pass any … Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts.”

The idea is that because annexation waivers are contracts, the state legislature can’t make laws that cause them to expire. Of course, the state of Indiana, which is an intervenor in the case, contends that it’s not all that simple.

In addition to its constitutional claims, Bloomington argues that the 2017 start to the current annexation effort should factor into the application of the 2019 law.

In 2017, after Bloomington initiated its annexation effort, but before it was complete, Indiana’s General Assembly passed a new law that had the effect of stopping Bloomington’s annexation effort. That 2017 law was eventually found to be a violation of Indiana’s state constitution by a 3–2 vote of the Indiana Supreme Court. The ruling came in late 2020.

The 2019 law voiding old annexation waivers was passed while Bloomington was litigating its claims on the 2017 law. So Bloomington argues that the 2019 law, even if constitutional, should not be applied to Bloomington’s already in-progress annexation attempts.

How does the constitutional question impact annexation outcomes?

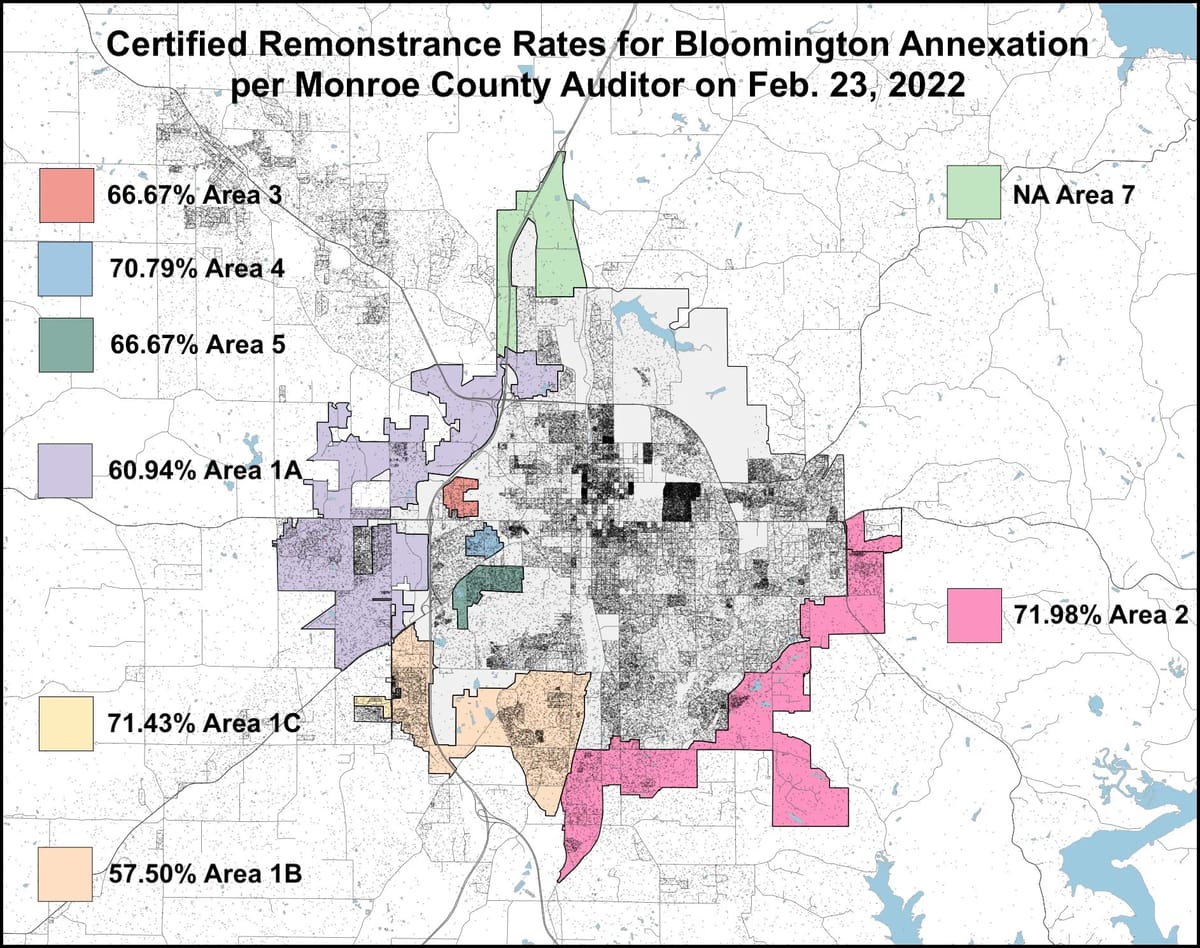

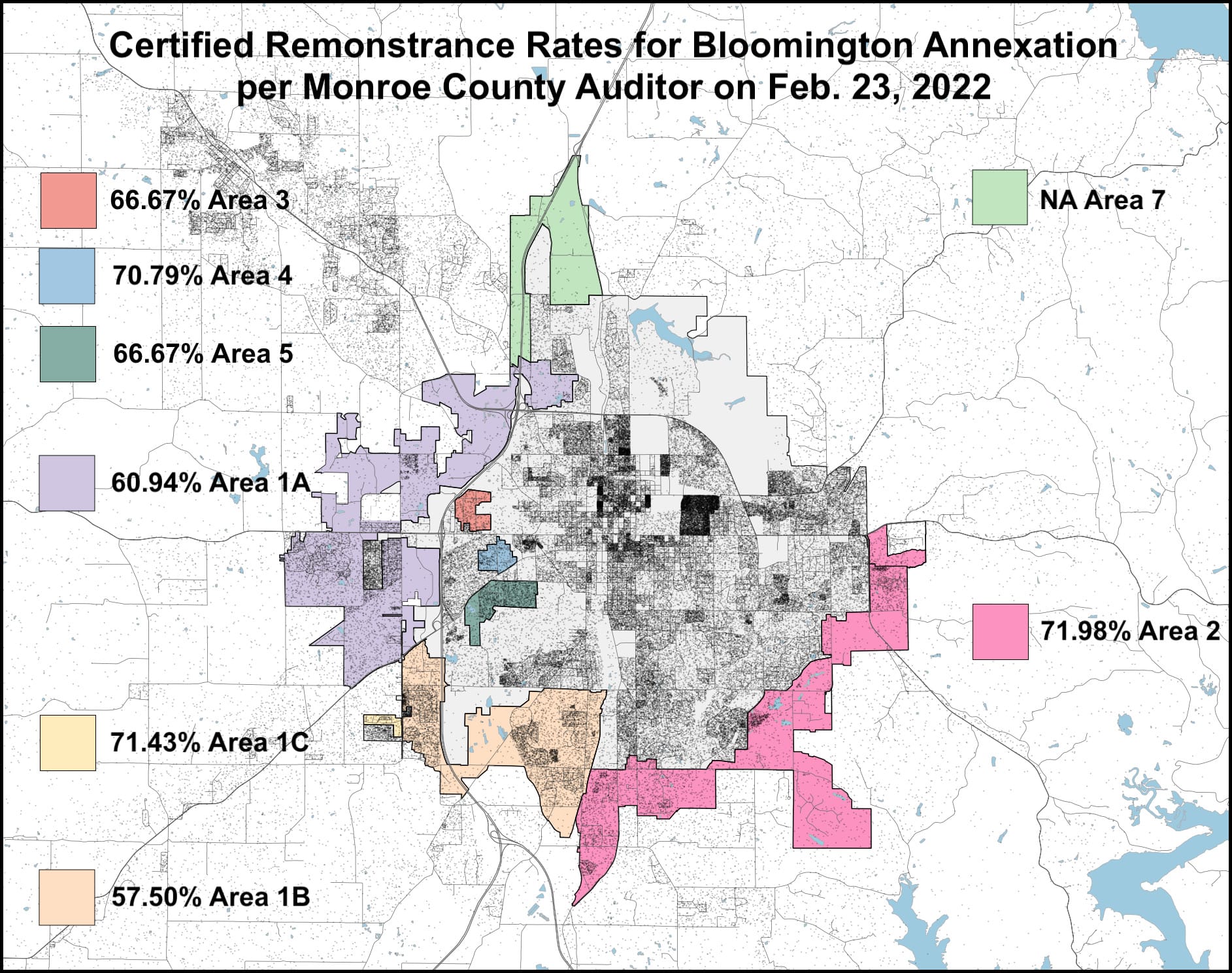

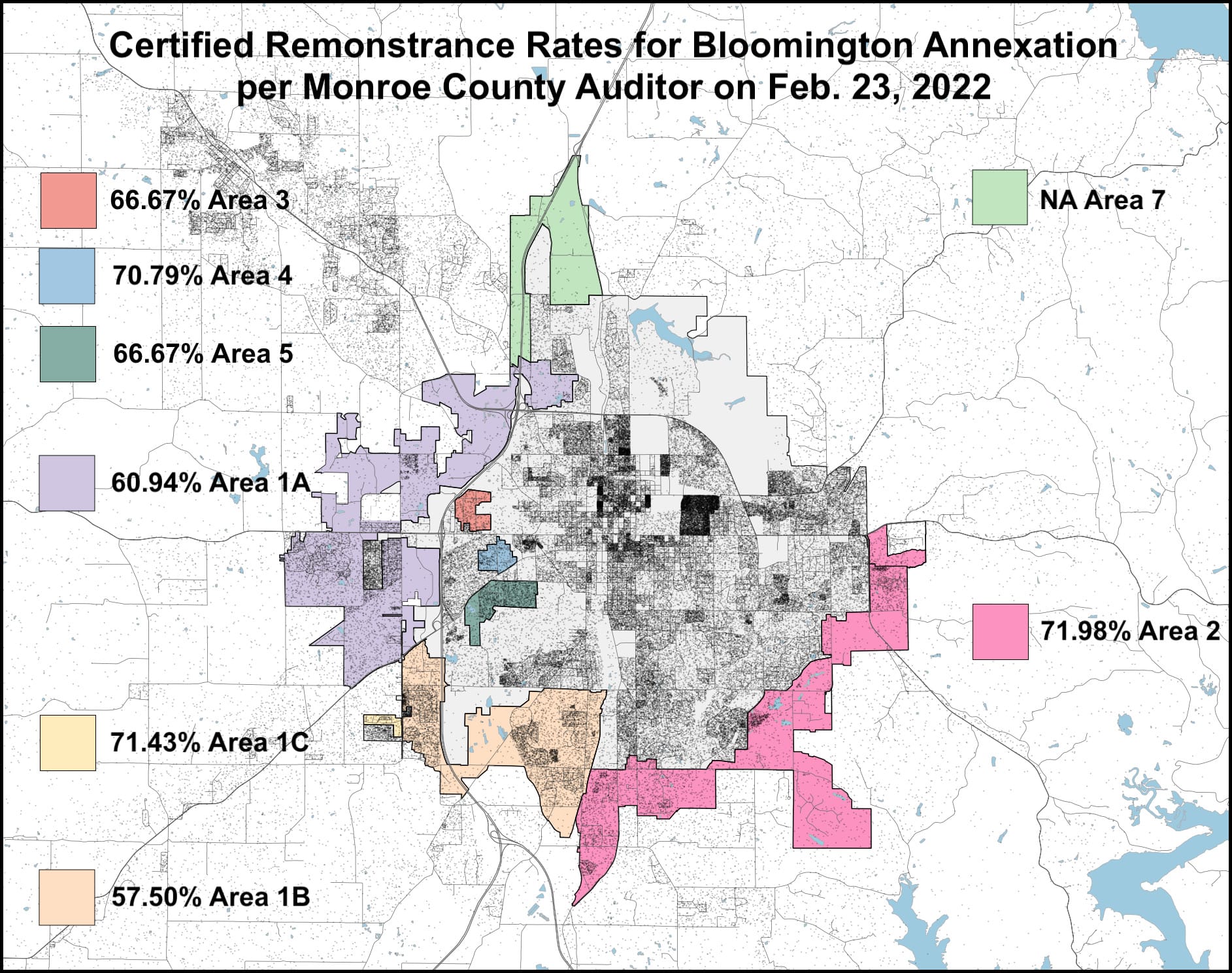

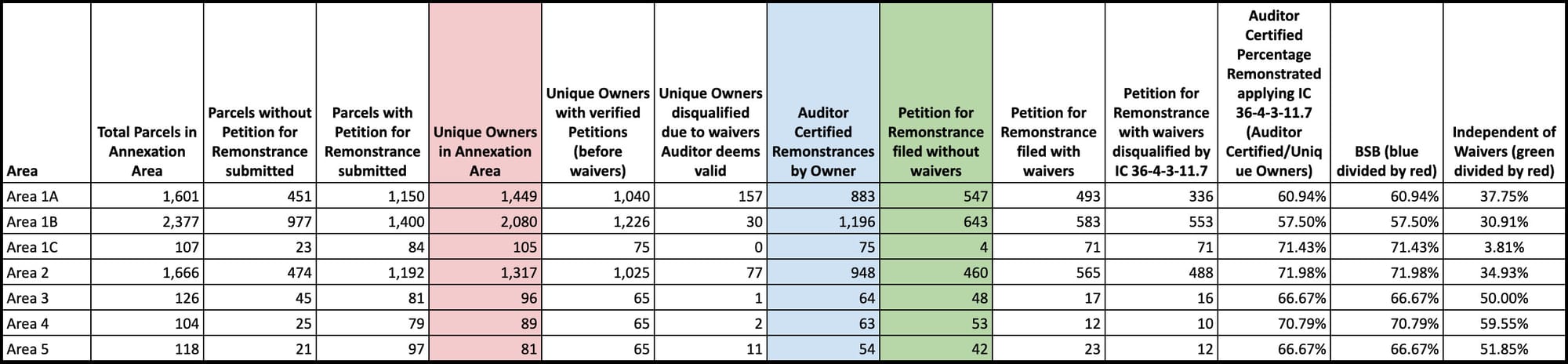

If Bloomington ultimately loses the constitutional case, and the 2019 state law is validated, then Bloomington’s annexation effort in all five areas (Area 1C, Area 2, Area 3, Area 4, and Area 5) will have automatically failed. That’s because more than 65 percent of landowners in those areas signed remonstrance petitions, which was enough to stop the annexation outright. (Left column in table below.)

But if Bloomington wins the constitutional case, the annexation in three of the five areas (Area 1C, Area 2, Area 3) will have succeeded without any further legal wrangling. (Right column in table above.) That’s because the number of valid remonstrance signatures in those areas would drop to 50 percent or less, if the law is found to be unconstitutional.

Bloomington’s annexation effort for the other two out of five areas (Area 4 and Area 5) would still be subject to a trial on the merits, even if Bloomington prevails in the constitutional lawsuit.

Why aren’t Area 1A and Area 1B included in the constitutional question?

Even though the case to be heard on Friday explicitly involves just five of the seven annexation areas, it began life as seven separate lawsuits, one for each annexation area. Those seven lawsuits were consolidated under one case. The cases were consolidated, because they involved exactly the same constitutional claims.

But the lawsuits for two of the areas (Area 1A and Area 1B) were eventually peeled out of the mix of seven.

They were already subject to separate legal action initiated by landowners, who had collected enough signatures, more than 50 percent, to force a trial on the merits of annexation in those areas. Landowners in Area 1A and Area 1B had not reached the 65-percent threshold, which would have been enough to stop annexation outright.

Area 1A and Area 1B were removed from the group of seven lawsuits, in connection with the separate legal action, which was, and still is, being heard by special judge from Lawrence County, Nathan Nikirk. The cases involving constitutional claims were initially assigned to a special judge from Owen County, Kelsey Hanlon.

For the trial on the merits for Area 1A and Area 1B, Nikirk had ruled that the trial would not take place until the litigation concerning the constitutional question was resolved. The logic behind that scheduling was that no trial on the merits would be necessary if Bloomington won the constitutional claims—because the signature count for both areas would fall under 50 percent.

But Bloomington wanted to go ahead with the trial on the merits for Area 1A and Area 1B as soon as possible. So Bloomington decided to forego any constitutional claims, just for Area 1A and Area 1B. In order to resolve the constitutional litigation for Area 1A and Area 1B, Bloomington voluntarily dismissed those two cases, with prejudice. That left just five in the set of consolidated cases to be heard on Friday.

The dismissals also cleared the way for Nikirk to schedule a trial on the merits for Area 1A and Area 1B, which are set to begin April 29.

What’s the connection of dismissed claims to Friday’s hearing?

The fact that Bloomington dismissed the two cases factors into a subsequent argument made by the state of Indiana, which is an intervenor in the case, and represented by attorney general Todd Rokita.

The idea is that by dismissing two of the lawsuits with prejudice, Bloomington deprived itself of the chance to litigate the constitutional claims for the remaining five areas—because it is the same legal issue, the same plaintiff, and the same defendant in each case. (The defendant is the county auditor, because it is the auditor who has the statutory task of counting remonstrance signatures.)

Bloomington’s counter argument includes the exact reasons for its voluntary dismissal of the two cases. The city simply wanted to comply with Nikirk’s insistence that the constitutional litigation for Area 1B and Area 1B be resolved, before proceeding with a trial on the merits.

The judge on Friday will be fully briefed on the way Nikirk ruled on that situation, and the logic that Nikirk applied, because it will be Nikirk himself who presides over Friday’s hearing.

Kelsey Hanlon, the special judge out of Owen County, who had previously been presiding over the constitutional cases, recused herself on the day of the scheduled hearing on Feb. 8.

Nikirk was assigned the constitutional case last month.

- 2022-03-29 Complaint filed by city of Bloomington.pdf

- 2022-05-18 Answer filed by intervener to Bloomington lawsuit.pdf

- 2023-10-10 Bloomington’s Response to motion for summary judgement.pdf

- 2023-10-30 Intervenor’s reply on cross motion for summary judgement.pdf

- 2024-01-03 Motion by Bloomington for Leave to File Sur Reply.pdf

Comments ()