Bloomington asks judge for ‘magic language’ so adverse annexation ruling can be appealed

Bloomington is looking to appeal the ruling that judge Nathan Nikirk made in mid-June, which found that a 2019 state law about annexation remonstrance waivers was not unconstitutional, as the city had argued.

Last Tuesday (July 2), the city of Bloomington filed a motion asking Nikirk to do one of two things.

The city wants Nikirk either to clarify that his ruling on the constitutional question was a final, appealable ruling, or else certify the city’s motion for an interlocutory appeal. An interlocutory appeal is one that is made on a ruling before the trial is over.

It’s a technical motion, but the takeaway is that Bloomington wants to appeal Nikirk’s ruling, one way or another. [Updated July 10, 2024: Nikirk has granted Bloomington’s motion to amend his ruling to include the “magic language” that the city had requested. That sets the stage for Bloomington to make its appeal as a matter of right to the court of appeals.]

The city’s motion does not appear to have been posted to the online docket until Monday (July 8), which is likely due to the week-long Monroe County government shutdown due to a cyberattack.

The reason for the city’s motion stems from the fact that there are still outstanding issues involved in the lawsuit, besides the constitutional question on which Nikirk ruled.

The outstanding issues relate to whether there were any defective remonstrance petitions that should not have been counted, that were nevertheless counted by the Monroe County auditor.

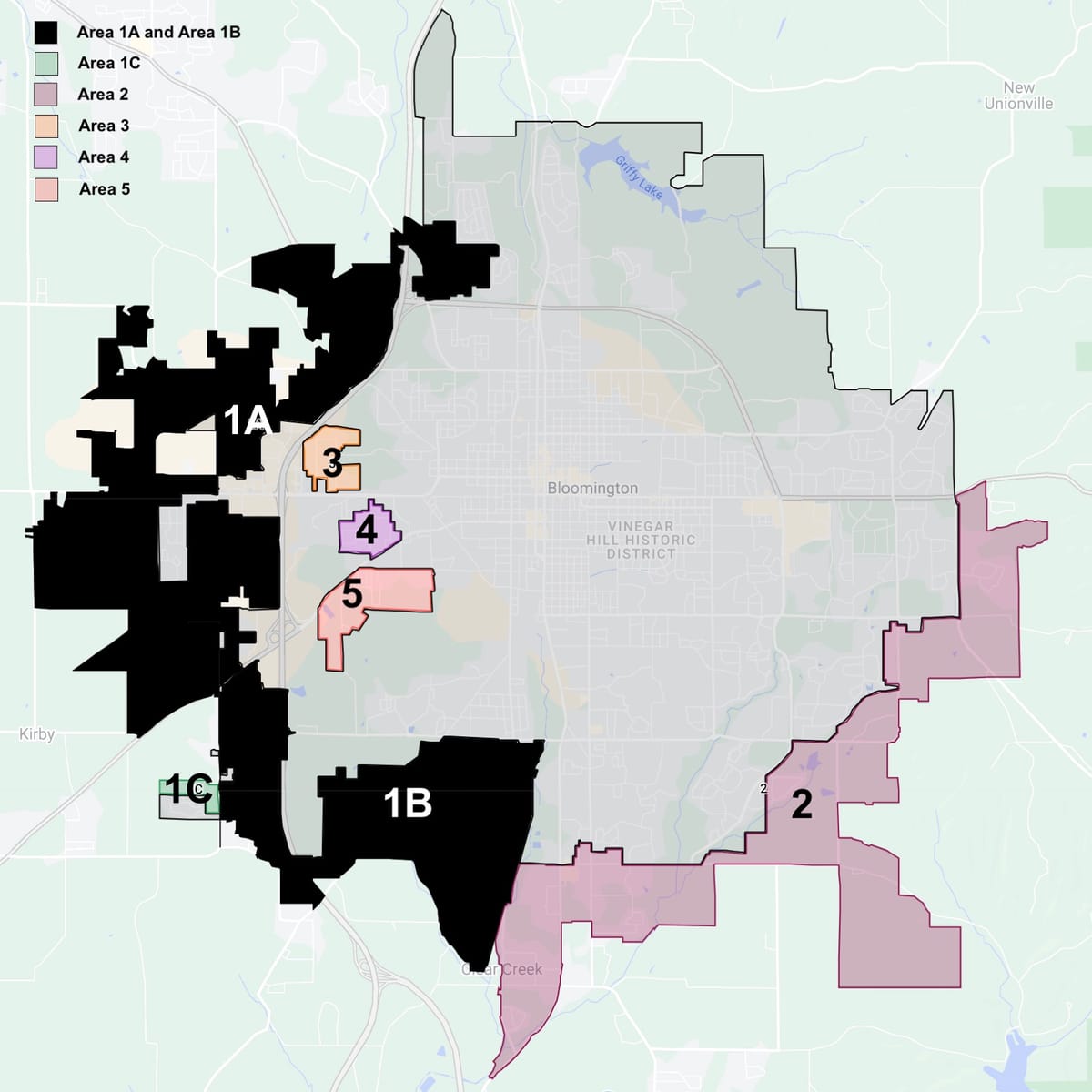

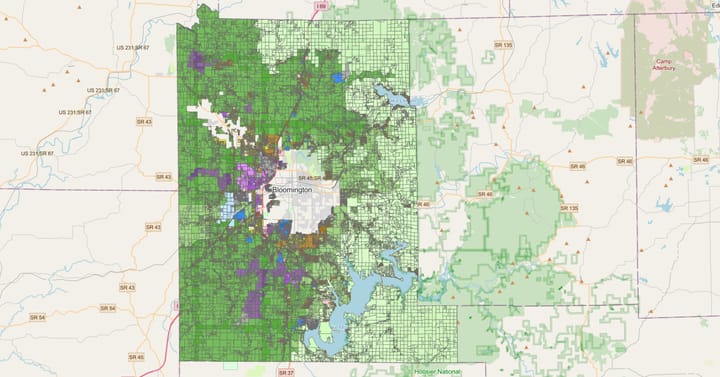

The same issue of potentially defective petitions was raised in the lawsuits for all five of the annexation territories—Area 3, Area 4, Area 5, Area 1C and Area 2. The city’s lawsuits for those five territories were consolidated into a single cause.

With its July 2 motion, Bloomington is basically asking Nikirk to add to his mid-June ruling what the Indiana Supreme Court has called “magic language,” to ensure that the ruling can be treated as a final ruling, which the city would have a right to appeal.

If Nikirk does not do that, then Bloomington wants Nikirk to let the city ask the court of appeals to hear an appeal before a final ruling is issued, that is, to hear an interlocutory appeal.

One difference between the appeal of a final ruling and an interlocutory appeal is that the court of appeals does not have to accept jurisdiction over an interlocutory appeal.

The “magic language” would come from a couple of trial rules, one of which is Trial Rule 54(C), which reads in part (emphasis added): “A summary judgment upon less than all the issues involved in a claim or with respect to less than all the claims or parties shall be interlocutory unless the court in writing expressly determines that there is no just reason for delay and in writing expressly directs entry of judgment as to less than all the issues, claims or parties.”

Nikirk’s mid-June order does note that his ruling does not dispose of one of the issues, but it does not include the exact wording, aka the “magic language,” saying there’s “no just reason for delay.”

Nikirk’s mid-June ruling on the constitutional claim came in connection with annexation ordinances enacted by Bloomington’s city council in fall 2021.

By the third week of February 2022, remonstrators in five of the seven areas that Bloomington wanted to annex had gathered enough signatures—from more than 65 percent of landowners—to block Bloomington’s annexation effort.

But the signatures depended crucially on the 2019 law, which affects the status of waivers of the right to remonstrate—which were signed by many property owners in exchange for a city sewer connection.

The 2019 law says that such waivers of the right to remonstrate are good only for 15 years. After 15 years, a property owner is free to sign a remonstrance petition.

Bloomington filed its lawsuits based on the idea that the 2019 law is a violation of the contracts clause of Indiana’s state constitution and the U.S. Constitution.

Without the 2019 law, many of the signatures of remonstrators would not have counted. In fact, without the 2019 law, none of the five areas would have had valid remonstrance signatures from more than 65 percent of landowners.

Bloomington’s July 2 motion is not related to separate litigation for two other areas (Area 1A and Area 1B) about which a bench trial was held in early May. A ruling on the merits of annexation in those areas could be expected towards August.

Comments ()