5–4 Bloomington council vote: 3 more stops, not just Dunn, OK’d for reinstallation on 7-Line bicycle route

“Wow. Just wow.”

That was how Bloomington city council president Sue Sgambelluri summarized the contentious debate that had just concluded on the question of reinstalling stop signs at three intersections, along the route of the 7-Line separated bicycle lane.

The intersections in question—Morton, Washington, and Lincoln—were not included in the ordinance that city engineer Andrew Cibor had asked the council to approve at its Wednesday meeting.

What Cibor had requested was enactment of an ordinance to make permanent just the stop signs that have already been reinstalled at 7th and Dunn streets, based on a 180-day order that he had issued.

By the end of the meeting, the reinstallation of stop signs at a total of four intersections had been approved by the city council.

About five hours before the start of the meeting, an amendment, which had been put forward by councilmember Dave Rollo, was posted in a meeting packet addendum. Rollo’s amendment added three more intersections where stop signs would be reinstalled on 7th Street—at Morton, Washington, and Lincoln streets.

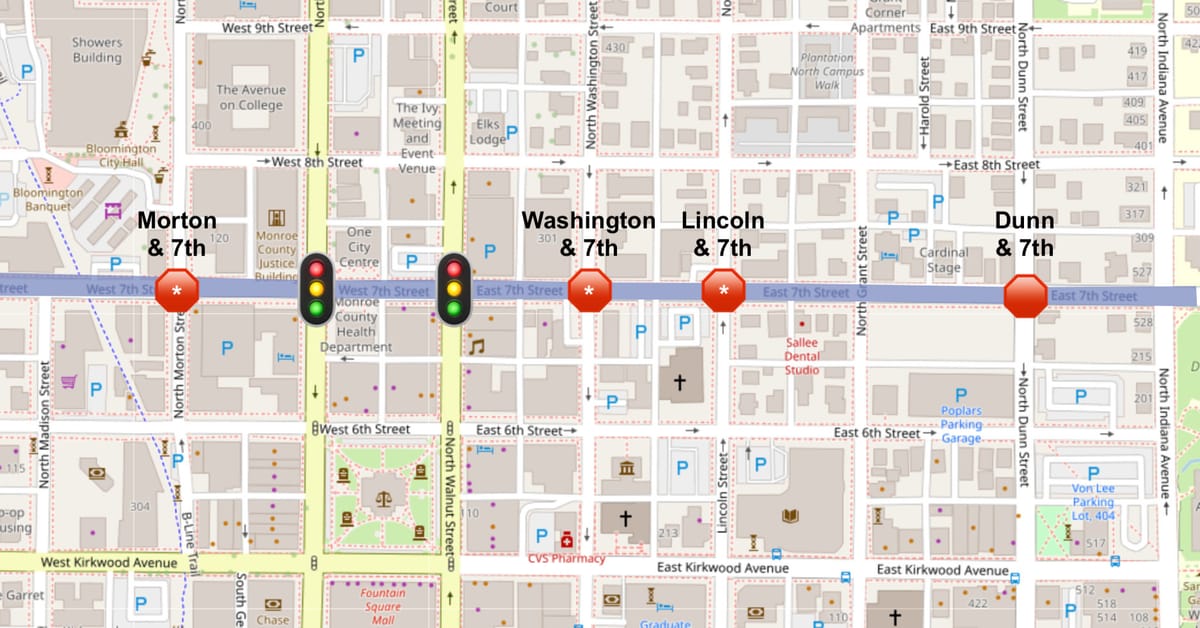

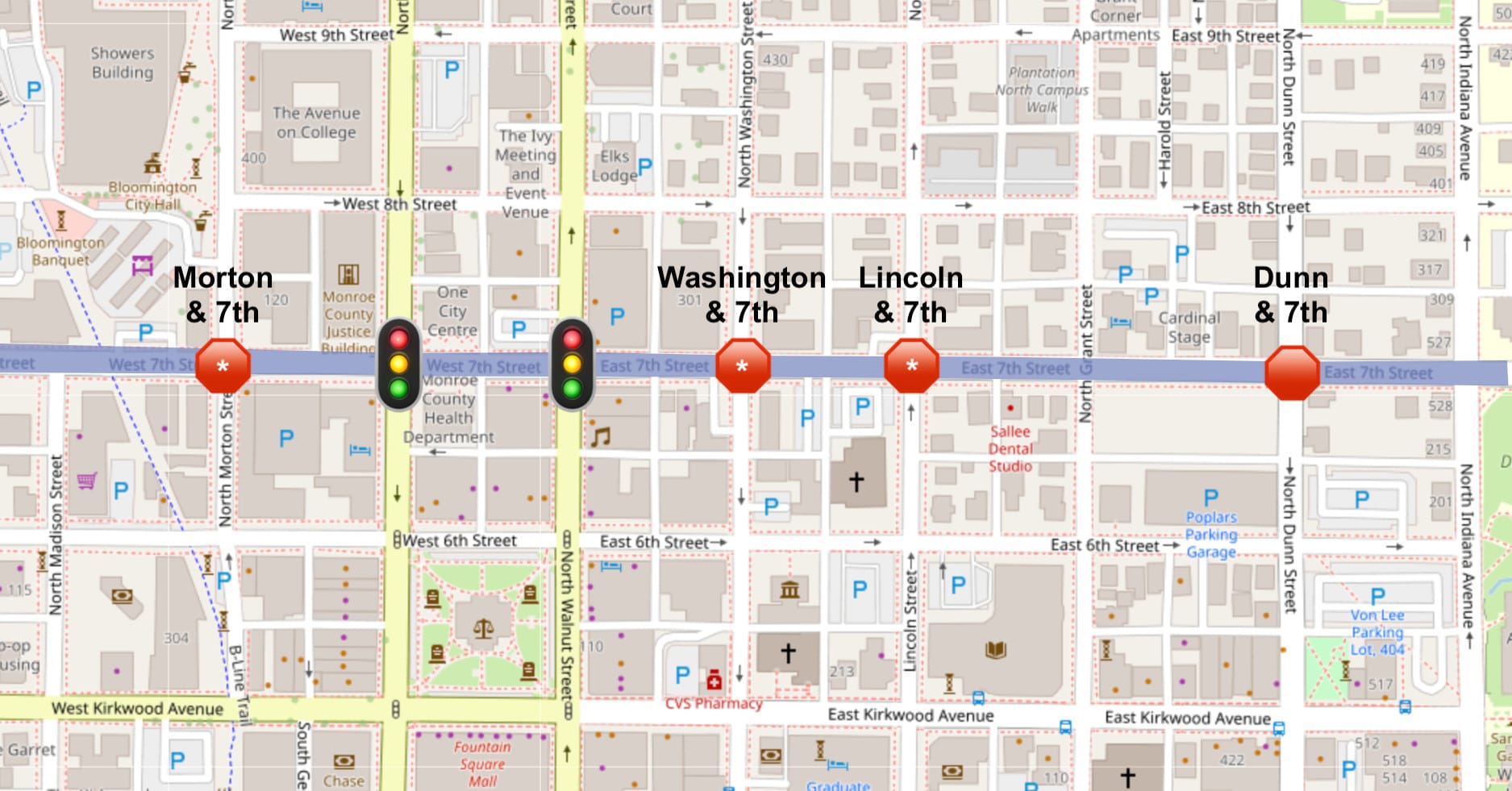

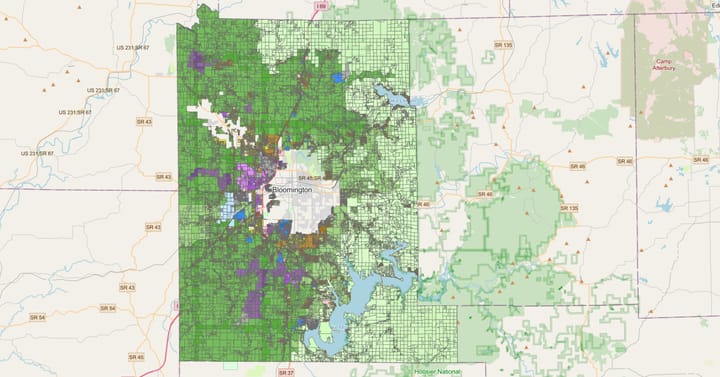

The operative word is “reinstalled” because the stop signs that previously stood at the intersections were removed in connection with the construction of the 7-Line separated bicycle lane on 7th Street. That’s a two-way bicycle lane that runs from The B-Line Trail near Morton Street past Indiana Avenue to the Indiana University campus.

In concert with the separated bicycle lane, the removal of the stop signs was meant to make the corridor, without a legal requirement to stop at each intersection, a more attractive option for cyclists.

Rollo’s amendment passed 5–4 along a familiar split on the all-Democrat council, between four self-described “progressives” and the others. Voting against Rollo’s amendment were Steve Volan, Kate Rosenbarger, Isabel Piedmont-Smith and Matt Flaherty.

Volan said the impact of the reinstallation of the stop signs would be “just to ruin the 7-Line.”

The ordinance, as amended, passed with the same 5–4 split.

The historical backdrop to Wednesday’s meeting included the city council’s unanimous approval to remove stop signs at all of the planned 7-Line intersections. That was about three years ago, in August of 2020.

A year after that (two years ago) in October 2021, when the 7-Line was completed and opened, the stop signs were removed.

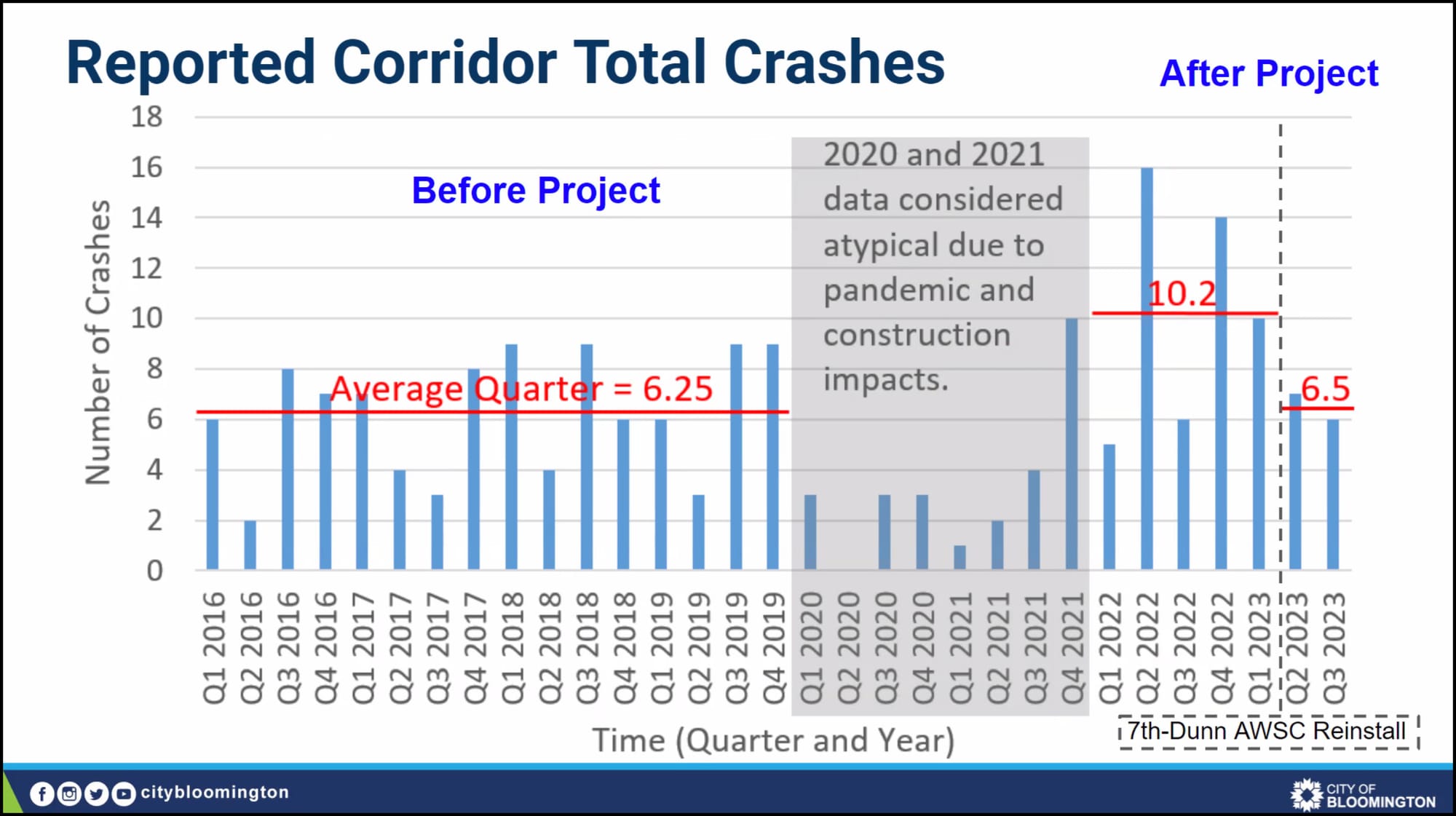

Earlier this year, city engineer Andrew Cibor reviewed the crash data along the corridor. Crashes were up compared to the pre-project numbers. He concluded that the stop signs should be reinstalled at all the places where they’d been removed—Morton, Washington, Lincoln, Grant, and Dunn.

Cibor ticked through some key conclusions: Pre-project crash numbers in the 7th Street corridor averaged around 6.25 crashes per quarter; but after the project was built and stop signs were removed, crashes averaged around 10.2 per quarter. After the stop signs were reinstalled at Dunn and 7th, the average crashes per quarter dropped to around 6.5 per quarter.

Cibor told the council on Wednesday that if all the stop signs were reinstalled, he believed that crashes would likely be further reduced.

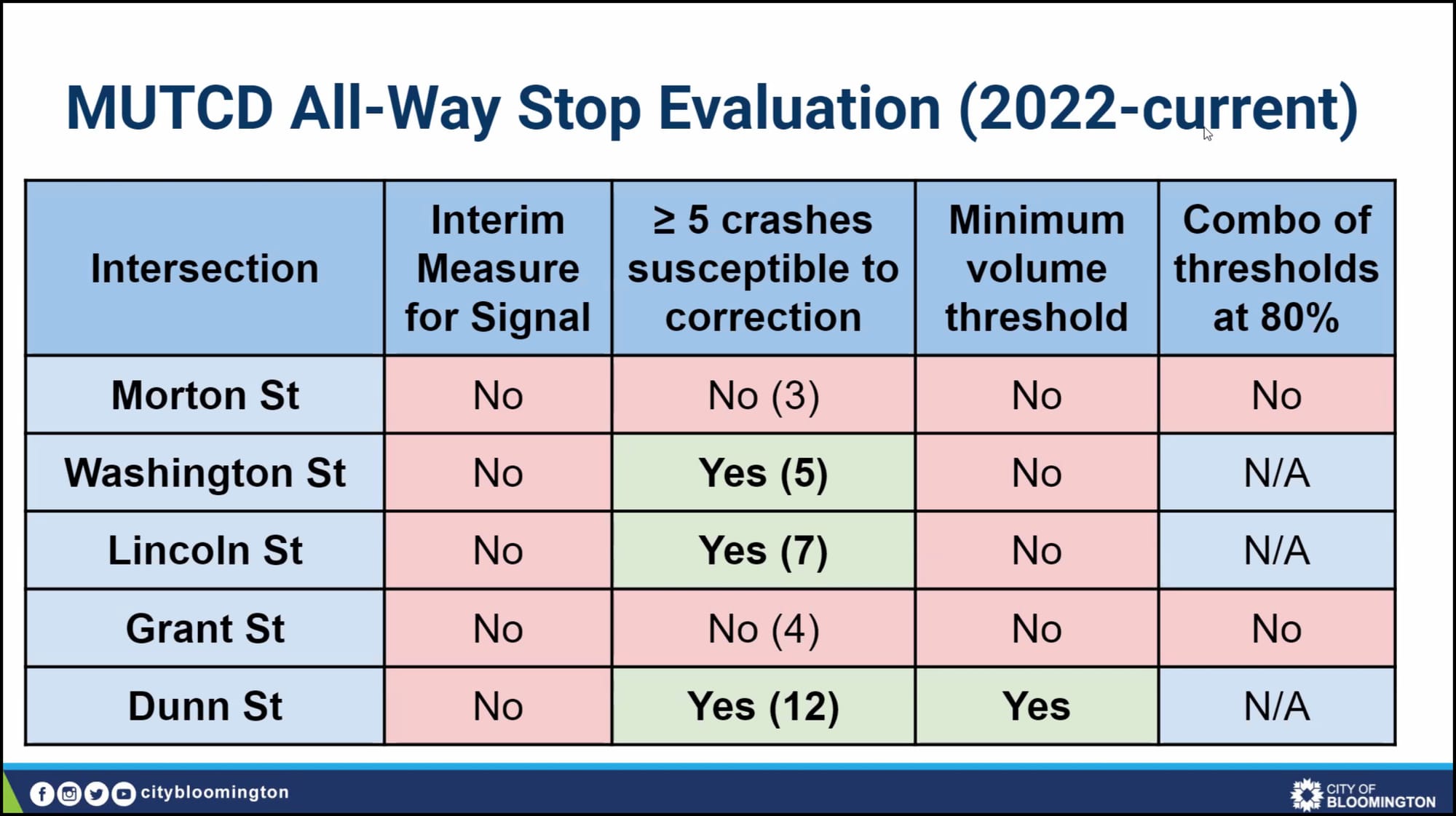

Another set of data presented by Cibor broke down crashes by intersection. The standards in the MUTCD (Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices) set a threshold for installation of stop signs at 5 crashes a year, if they were susceptible to correction by a stop sign.

Since 2022, the intersections at Dunn, Lincoln and Washington met that threshold for installation of a stop sign. The intersections at Morton and Grant did not. Rollo’s amendment did not reinstall a stop sign at Grant.

A proposed amendment to Rollo’s amendment, put forward by Isabel Piedmont-Smith, would have removed Morton from the mix, leaving a stop sign there. Piedmont-Smith’s proposal failed, on a vote that split along the same lines as the others.

When Cibor presented his findings to the traffic commission and the bicycle and pedestrian safety commission earlier this year, both groups supported the idea that only the stop sign at Dunn Street should be reinstalled.

Both groups rejected Cibor’s recommendation that the other stop signs be removed. Cibor then used his authority under city code to impose a 180-day order to reinstall a stop sign only at 7th and Dunn streets. The 180-day order on the Dunn stop sign installation was set to expire on Oct. 9.

On Wednesday, Cibor said that the response from the traffic commission and the bicycle and pedestrian safety commission factored into his decision to ask the council to enact an ordinance that reinstalled a stop sign only at 7th and Dunn. Responding to a question from Piedmont-Smith, Cibor said the ordinance he had proposed was “very much reflecting and wanting to respect the opinions of our bicycle pedestrian safety commission and our traffic commission.”

Cibor also said his decision not to ask the council to reinstall stop signs at the other intersections was his effort to be “mindful of the reason the stop signs were removed in the first place—to help encourage and facilitate an east-west corridor.” Cibor also said there was merit in the crash data to consider reinstalling stops at other intersections besides Dunn and 7th streets.

Tackling the 7th and Dunn intersection now doesn’t preclude additional action again in the future, Cibor said.

Councilmember Kate Rosenbarger asked Cibor about Rollo’s proposal: “Does the administration recommend this amendment?” Cibor did not respond directly, but his answer added up to a no: “The administration brought forward an ordinance that we are advocating for.”

Rollo sketched out the reasoning behind his proposed amendment. For the whole stretch between Walnut and Dunn there are no stop signs that would allow for ease of pedestrian crossing, Rollo said.

Rollo also pointed to Cibor’s initial recommendation for reinstallation of all the stop signs that had been removed.

Rollo summed up by saying, “My principle aim is for safe pedestrian crossing, but it also addresses the crash hazard at Washington and Lincoln.” Rollo said he added Morton Street, because of the heavy pedestrian uses, especially during events like the city farmers market. Rollo added “It’s also been requested by a number of constituents.”

Over the course of the deliberations, it emerged that among those who had advocated for reinstallation of stop signs at Morton was someone Rollo described as “a judge who asked that Morton be a priority because of court personnel that needed to cross at that intersection.”

Speaking from the public mic on the Zoom platform against the reinstallation of stop signs at Lincoln and Washington was Hopi Stosberg, who is the Democratic Party nominee for District 3 city council on the Nov. 7 ballot. She’s competing with Republican Brett Heinisch for that seat.

Stosberg pointed to the reasoning used by the bicycle and pedestrian safety commission in rejecting the engineer’s recommendation at those two intersections—they’re in the middle of a hill. Stopping causes bicyclists to lose momentum.

As for the Morton Street intersection, Stosberg said, “Honestly I have no concern with reinstituting a stop sign at Morton… because Morton is not in the middle of a hill.” Stosberg added, “And I do agree anecdotally that that intersection does get, especially on farmers market days, really dicey with cars.”

During public commentary, Pauly Tarricone spoke against Rollo’s amendment, because it undercuts the goal of promoting cycling as a transportation option. Tarricone serves on the bicycle and pedestrian safety commission. Also speaking during public commentary against Rollo’s amendment was Ben Fulton.

Rollo’s mention of constituents drew a sharp question from councilmember Steve Volan: “Well, how many constituents would you say caused you to create this amendment?”

Rollo replied, “Oh, probably less than 10.” Rollo added that he and councilmember Susan Sandberg, who hold joint constituent meetings, had heard from older residents that crossing 7th Street is a challenge without stop signs.

There’s a bit of history that forms the backdrop of the exchange between Rollo and Volan. Rollo represents District 4. Volan represents District 6. They have both served on the council for about 20 years. The result of redistricting put both of them in District 4 for this year’s city council elections. Rather than face Rollo, Volan ran for one of the three at-large seats and came sixth in a Democratic Party primary field of seven. Rollo will return to the council in 2024, but Volan will not.

Volan responded to Rollo by saying, “Last I checked, the 7-Line was in District 6. I’ve had no constituent complaints about it.” Volan then drew into the discussion a traffic calming project in Rollo’s district. He asked Rollo: “If your constituents can complain about the 7-Line, why is it that people outside of the Hawthorne-Weatherstone Greenway shouldn’t be able to complain about that green space?”

Volan called Rollo’s proposal “an amendment inspired entirely by constituents who are not from District 6… What should I think?”

Later in the meeting, Volan pointed to the fact that no one from the public had spoken in support of Rollo’s amendment. “I think that the utter lack of testimony from anyone other than councilmembers for this amendment, and the testimony by those who are against this amendment, illustrate that those who had supported are out of step with Bloomington, out of step with the pedestrians and bicyclists who benefit from this.”

Volan added, “To say that restoring the stop signs is for the sake of pedestrians crossing is, I find, to be an unfortunate excuse for continuing to allow cars to cross.”

Flaherty responded to Volan by cautioning against drawing any conclusions based on who speaks at public commentary: “I wouldn’t go so far as to say that we can draw any conclusions from who shows up and doesn’t at a meeting necessarily, and who’s able to weigh in.”

Flaherty continued, “There are all sorts of barriers to doing so.” Flaherty added, “And I certainly believe my colleagues who support this amendment…who they’ve heard from, and what they think about it. I respect that opinion. I think it’s fine.”

Flaherty landed on the side of the ordinance as proposed by Cibor, which would authorize the permanent reinstallation of stop signs just at the one intersection of Dunn and 7th Street.

Councilmember Jim Sims responded to Volan’s characterization of those who supported Rollo’s amendment (as Sims did) as “out of step.” Sims did not think it was appropriate to characterize a council colleague as “out of step” just because they have a difference of opinion.

Councilmember Kate Rosenbarger gave commentary along the lines of Volan’s “out of step” remark by citing the remarks of an unnamed councilmember who had sought reelection this year, but had not won in their primary. That councilmember had said, “We’ve done enough for bike and ped,” according to Rosenbarger. “I feel like the voters disagreed with that,” Rosenbarger said.

Redistricting put Rosenbarger and Sgambelluri both in District 2. Rosenbarger prevailed in that primary race between the two incumbents.

Rosenbarger noted that there would be a new city council taking office in 2024. Five of nine will be new. Rosenbarger guessed there would be priorities on the new council that are different from the current council.

Volan picked up on the theme of the next council, even though he will not be a part of it. About that night’s vote, Volan said, “I’m expecting a majority is going to rule to put the stop signs back.” But he added, “I’m also expecting that come 2024, a majority is going to rule to undo it.”

Volan said he expects the next council to undo the reinstallation of stop signs on 7th Street because “It’s clear that it’s reactionary. It’s clear that the data support leaving the design as it is.” Volan continued, “And it’s clear that my colleagues have not thought enough about putting stop signs in other places, or stopping cars in other places. They’re only focused on the 7-Line.”

Volan then responded to remarks from councilmember Susan Sandberg who had earlier said, “Data is important. Yes, it is. But so are the feelings of the people who put you in office—the people who are expecting you to fight for them.”

Volan said, “We should not let people’s feelings be the final—or why bother to put together a transportation plan? Why bother to have a comprehensive plan, if we’re just going to shrug it off and ignore it?”

Volan continued in a sarcastic vein: “Let’s just rule everything by anecdote. Well, if the people I talked to at the farmers market feel like maybe it’s not working, maybe I don’t really care about the expertise of our chief engineer. What are his qualifications anyway? What does he know? My feelings are what matter.”

Comments ()