$6.25 paid, $120 fined: User error with parking payment app means pricey farewell 'gift' from Bloomington to recent IU grad

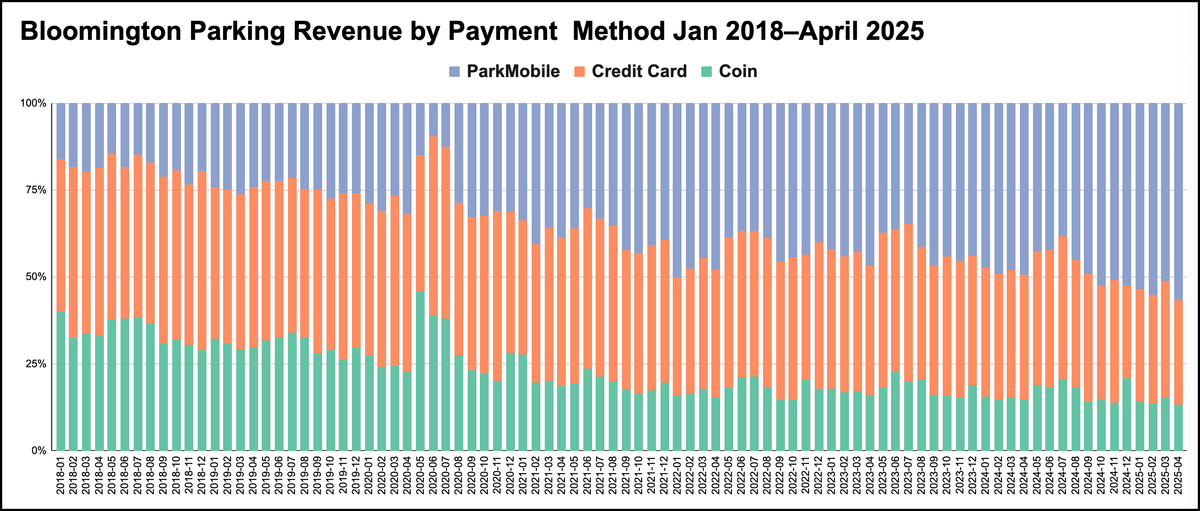

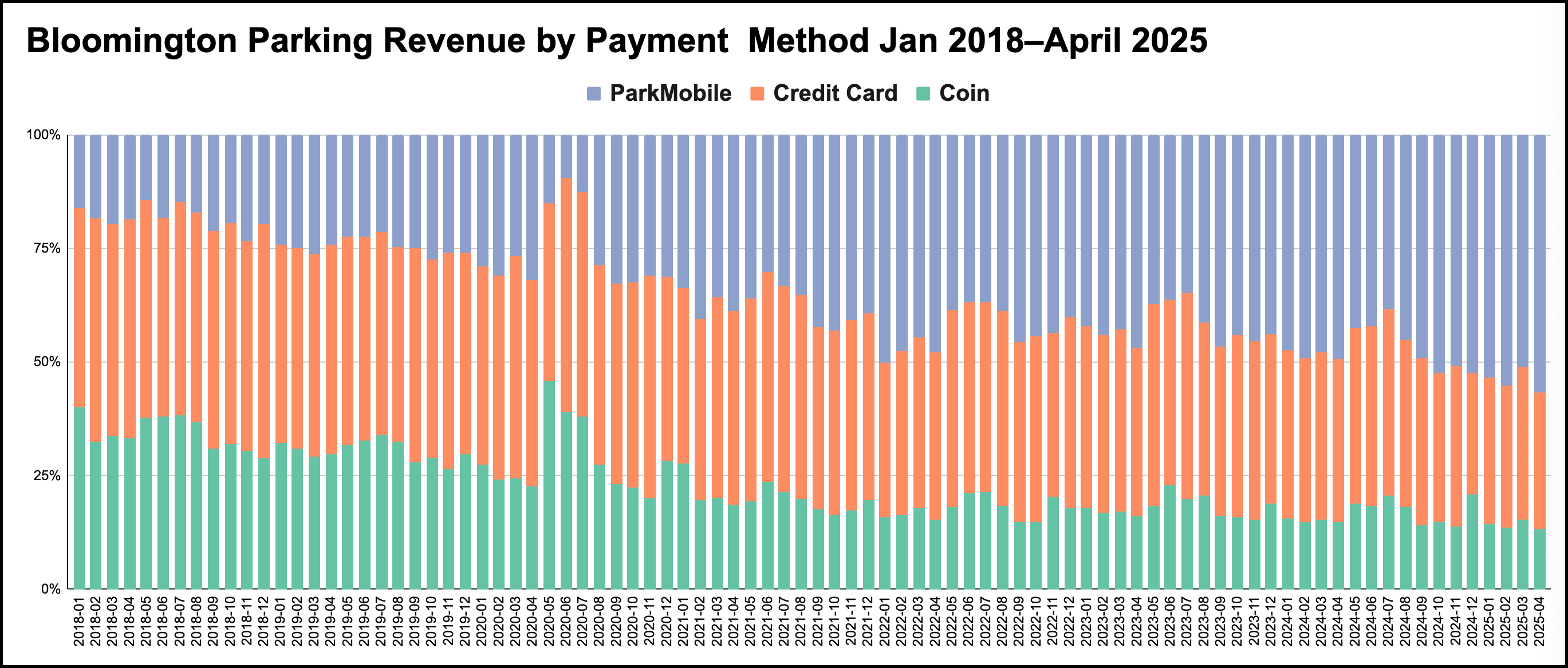

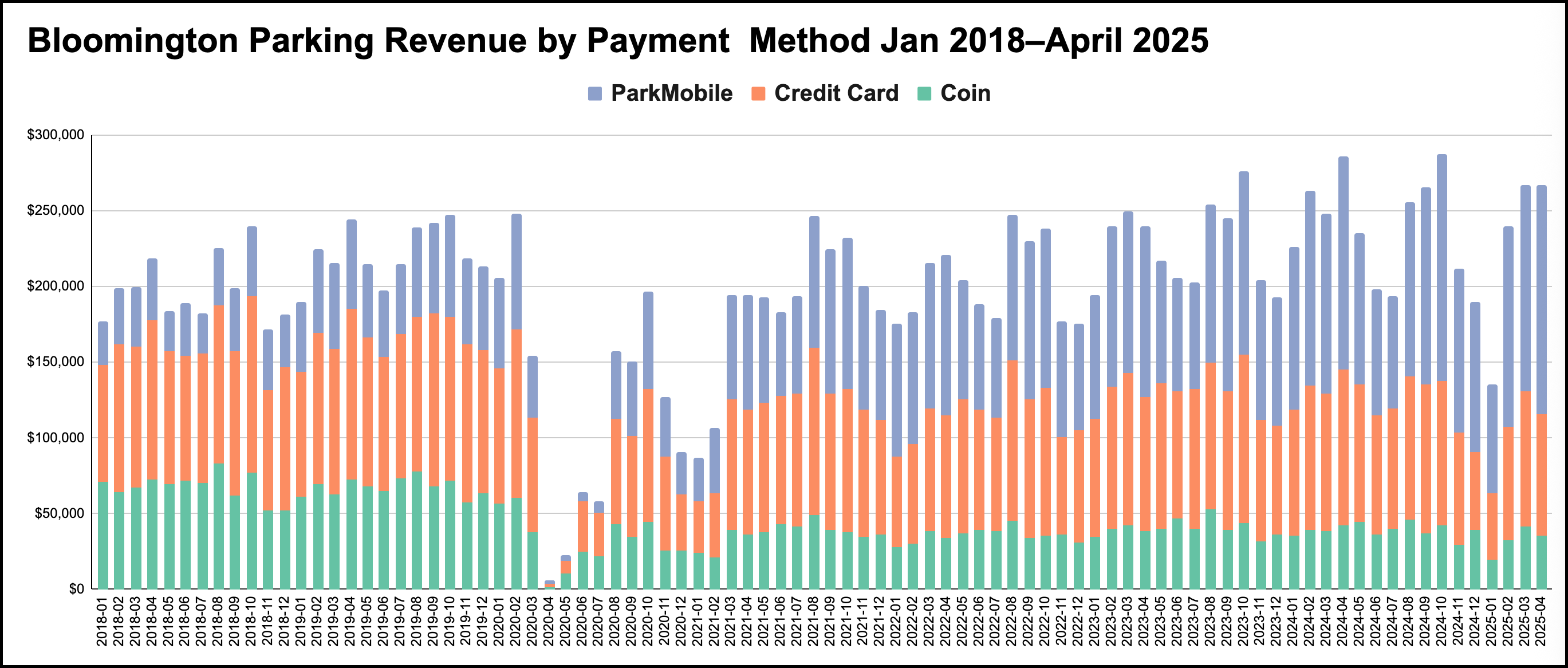

In 2024, about $470,000 worth of coins were fed into Bloomington's roughly 1,450 parking meters in the downtown area. That's about 17% of the $2.85 million in total revenue the city received from parking meters.

The other two methods of payment are swiping a credit card at the meter and the ParkMobile app, which in 2024 accounted for 36% and 47% of revenue, respectively.

This year, the city's parking meter revenue looks like it's on pace to hit a total similar to last year—that is, around $3 million. But through April 2025, the relative share of the city's parking meter money that is collected through the ParkMobile app has grown to about 59%.

All those numbers are based on a B Square analysis of data provided by the city through a records request.

One of the selling points for the ParkMobile app is that it can help motorists avoid parking tickets, because they can add time to the meter from their smartphone, wherever they happen to be. That means an interesting conversation over coffee or a stronger drink doesn't have to get interrupted by going outside to feed the meter.

Despite the usage of ParkMobile, based on information in the city's online financial system, Bloomington has collected at least $175,000 in parking fines so far this year.

Adding $6.25 to this year's ParkMobile total on April 15 was Abhishek Murli who was at the time a student at the Indiana University's Kelley School of Business. But Murli also added $120 to the city's total of fines for that same parking session, which lasted 6 hours and 15 minutes. (The city's parking rate is $1 per hour.)

The amount of $120 is easy enough to understand—two $30-tickets were issued during the six-hour period, which then doubled to $60 apiece after they were not paid or appealed within 14 days.

But why were two tickets issued for non-payment of the parking session? That's because under Bloomington city code, non-payment at a parking meter can be treated as a separate violation every two hours.

So if Bloomington parking enforcement officials had enforced the code with maximum efficiency, Murli could have received three tickets.

The part of the story that is harder to understand is why Murli was given even one ticket, when he could document that he paid for his parking with the ParkMobile app. He sent The B Square the receipt showing he paid.

But in Bloomington, unlike in some other cities where ParkMobile is used, the payment is connected not to the parking space, but rather to the vehicle, through the license plate number. Murli had previously been using a different car when he parked in Bloomington, and when he switched to a different vehicle, did not update the license plate number for his ParkMobile account.

When Murli reached out to The B Square, he put it like this: "I had a loaner rental vehicle with Alabama license plates which I just returned and came back to Bloomington with my IL [Illinois] license plates car. Unfortunately I forgot to update the tag in the Parkmobile app."

That meant even though he paid for the 6 hours of parking, when Bloomington parking enforcement officers checked his license plate for a current ParkMobile payment, they could not find one. And that meant they wrote a ticket. And at least 2 hours after that, another ticket was written.

Murli added, "I just graduated from Kelley School of Business and have called Bloomington home for the last 4 years so this parting gift from the City stuck like a lump in my throat."

The chance for appealing the tickets expired at the same time the fines doubled—at the 14-day mark. The scenario Murli described is a common one for the Bloomington's city clerk's office, which handles the appeals for parking tickets.

Given that the window for an appeal has closed, it does not help Murli's cause, but according to the clerk's office staff, a simple mismatch between the license tag for the vehicle and the tag in a ParkMobile account can be grounds for dismissal of a ticket. They call it a "user error." That's as long as the ParkMobile payment was made before the ticket was issued.

Better than half of all parking ticket appeals are successful, according to the city clerk's office records.

Reached by The B Square, city clerk Nicole Bolden said that when a policy choice was made to accept parking meter fees through the ParkMobile app, a conscious decision was made to tie the payments to the vehicle, not the parking space. It's the difference between paying for the specific space, and paying for the vehicle to park in some space. The city of Indianapolis also uses ParkMobile, but ties the payments to spaces, Bolden said.

When she visits Indianapolis, she uses ParkMobile to pay for parking—by entering the specific zone she's parking in, Bolden said. Here in Bloomington, the ParkMobile app is tied to the license plate number in her account.

But Bolden is sometimes also part of the gradually shrinking number of motorists—generating 13% of revenue so far this year—who put metal currency into the parking meters. She told The B Square that whenever she is parking for just a short while, she uses coins.

Comments ()