Activist tests right to write “vote” on Bloomington street, protests policy on art in public right-of-way

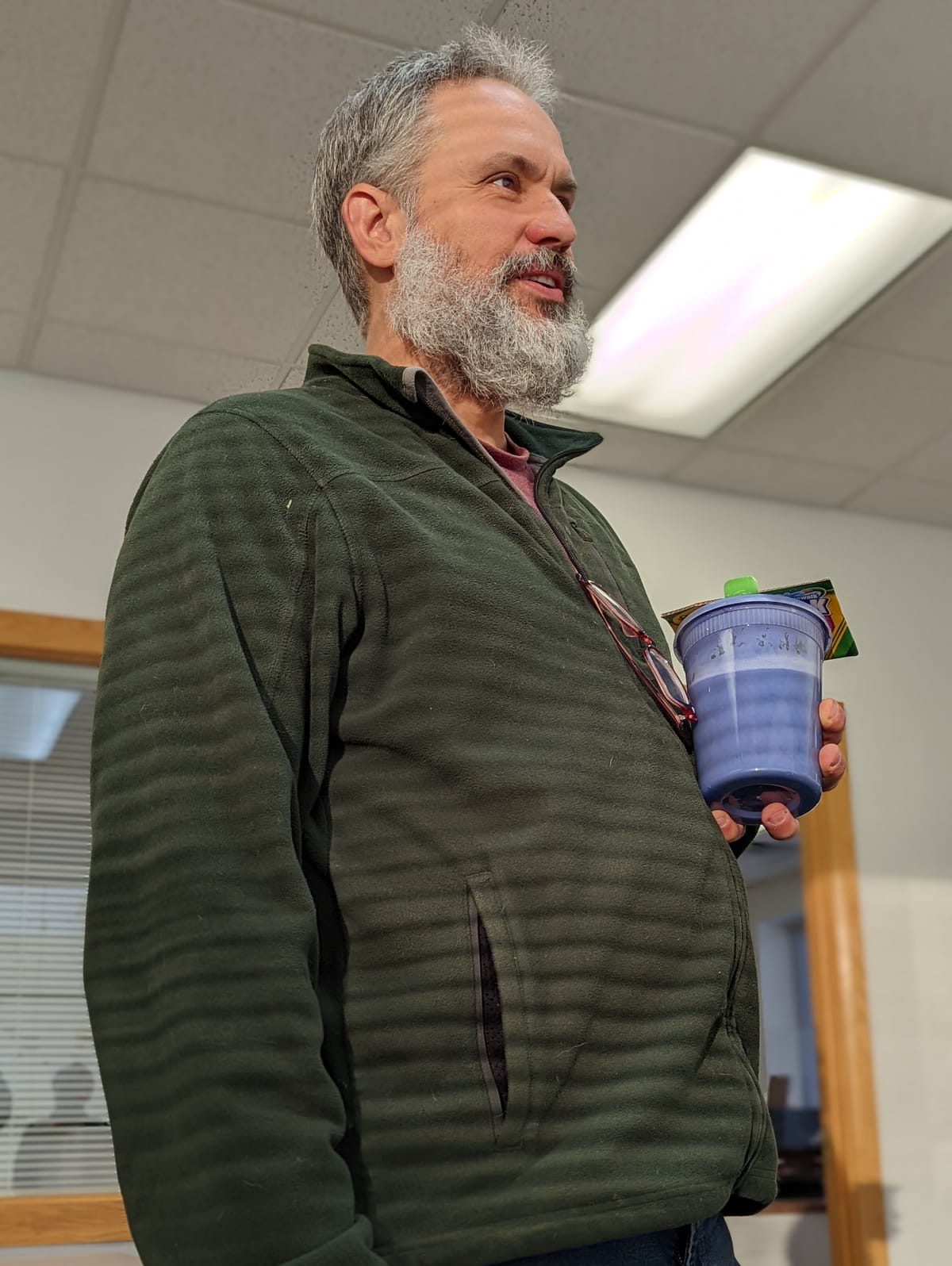

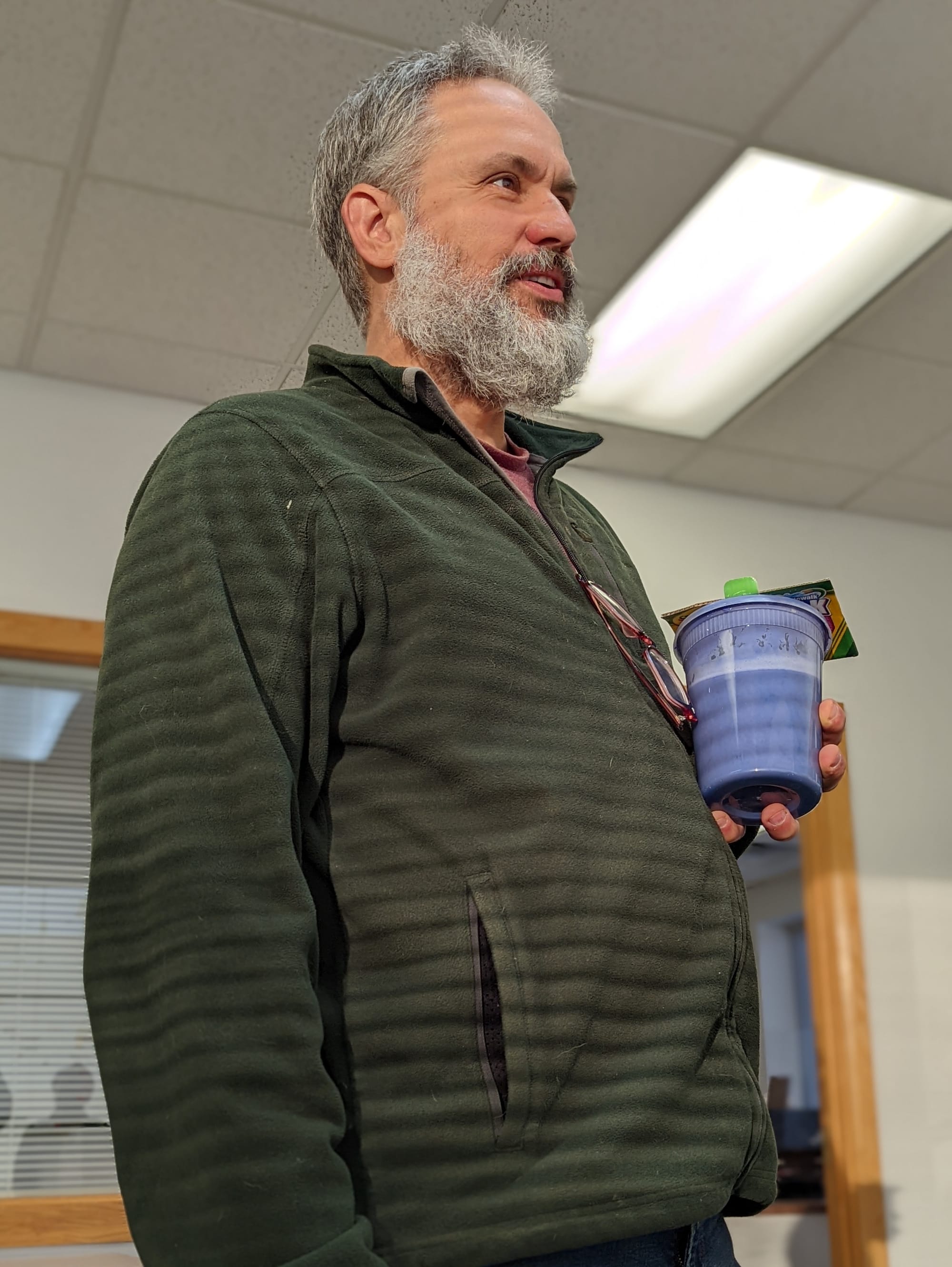

Around 9 a.m. on Wednesday morning, Bloomington area resident Thomas Westgård started dolloping a purple compound onto the asphalt at 7th and Madison streets near Monroe County’s Election Central.

After a few minutes, the word “vote” was spelled out in purple on the pavement.

It was a coincidence that Wednesday was also the first day when candidates in Bloomington’s city elections could file their official paperwork.

For Westgård, it was the right time and day to write “vote” on the street, because a status conference was on a federal court calendar for about an hour later, for a case that involves the right of private individuals to install art in Bloomington’s public right-of-way.

In November 2022, the judge issued a preliminary injunction against Bloomington, ordering the city to establish criteria for applications by private individuals to install art in the public right of way.

The deadline for the city to set the policy was Jan. 2. Bloomington’s board of public works adopted the policy at its final meeting last year, on Dec. 20, 2022.

The city is required to allow the plaintiffs in the case—Kyle Reynolds and the Indiana University Chapter of Turning Point USA—to apply for installation of an “All Lives Matter” mural under the new policy. The phrase is associated with opposition to the “Black Lives Matter” movement.

The lawsuit stemmed from the city’s denial of a request in 2021 by Reynolds to paint his mural on Kirkwood Avenue.

According to the plaintiff’s legal council, on Dec. 19 Reynolds again requested that he be allowed to paint an “All Lives Mural” on a Bloomington street. That renewed request came after the city’s new art policy was released in the board of public works meeting information packet, but before the vote to adopt it the following day.

Reynolds has not yet received a response from the board of public works, according to his legal counsel. There’s not another date on the case calendar, but the status conference scheduled for Wednesday might have charted out some kind of expected course for the two sides.

Westgård spoke against the new art policy at the Dec. 20 board of public works meeting, criticizing it for going beyond the “time, place and manner” restrictions on free speech that courts have long since settled as permissible.

Westgård introduced himself to the board of public works as someone who’d been involved in the free speech issues surrounding Bloomington’s farmers market a few years ago.

The city farmers market episode is part of what Westgård describes as a history of Bloomington’s inconsistent approach to speech in public places.

On Wednesday morning, Westgård chatted with Monroe County clerk Nicole Browne inside Election Central—assuring her that his protest was not against the clerk’s office.

He summarized for Browne what he was up to that morning—to highlight what he analyzes as Bloomington’s pattern of viewpoint discrimination for speech in public spaces. The new art policy continues that pattern, Westgård says.

Westgård told Browne he’d been arrested in 2019 for holding a sign protesting a farmers market vendor for its ties to white supremacists. But he had not been arrested for holding a sign in support of legalizing abortion and walking through the city’s farmers market, after the Roe v. Wade decision was overturned in June 2022, Westgård said.

Westgård put it like this: “So when I’m saying something that they like, they let me do it. When I’m saying something they don’t like, they arrest me. ”

For permanent art, expected to last longer than a week, Bloomington’s new policy on private art in the public right-of-way bans “speech”—defined as letters, words, and other universally recognized symbols. So writing the word “vote” on the street would violate the policy on permanent art, but might be allowed as temporary art, depending on how another part of the policy is analyzed.

For any art, temporary or permanent, the policy forbids the depictions of “activities, materials, images, or products that are not legally available to all ages.” Voting is an activity that is not available to people under 18 years old. So a mural depicting someone casting a ballot would not be allowed under the policy.

But it’s not clear if Bloomington’s new policy against “depicting” age-restricted activity would be violated by writing the word “vote” on a street—if it were temporary, and escaped the prohibition against words,

Parked at the Election Central parking lot on Wednesday morning, monitoring Westgård’s work was a Monroe County sheriff’s deputy.

Westgård had said he was hoping to be arrested for his art that morning.

But the deputy did not move to arrest Westgård, saying that he did not have jurisdiction over the street.

After Westgård departed the scene, Bloomington police officer arrived and visited with the sheriff’s deputy to confirm there was not an issue that needed followup.

Comments ()