Amid shift in Bloomington street oversight, Flaherty gets city council nod for new transportation group

Bloomington's new transportation commission got its first seat filled on Wednesday night (March 26), when Matt Flaherty prevailed over Andy Ruff in a 5–4 vote on the city council, to become the appointment from the council's own membership.

The new commission, which was established by the city council in February, came at the same time three other commissions were dissolved: traffic commission; bicycle and pedestrian safety commission; and the parking commission.

The purpose of the transportation commission is to guide "the city's transportation endeavors through a comprehensive framework which seeks to provide adequate and safe access to all right-of-way users while prioritizing nonautomotive modes and sustainability."

In the two-person race for the appointment, Flaherty and Ruff each nominated and voted for themselves. Ruff had support from: Dave Rollo, Courtney Daily, and Isak Asare. Flaherty got votes from: Kate Rosenbarger, Isabel Piedmont-Smith, Hopi Stosberg, and Sydney Zulich.

Wednesday's discussion about the transportation commission appointment highlighted a recent big shift in the way the council's potential role in deciding permanent changes in city roadways has been analyzed. Bloomington's corporation counsel, Margie Rice, has pointed to the statutory authority of the city's traffic engineer, as opposed to the city council, to decide questions of permanent changes to roadway infrastructure.

The new nine-member transportation commission will also get appointments from the mayor (2), the plan commission (1), board of Bloomington Transit (1), and board of public works (1).

The council has three other appointments to make, two of which have to be "residents living within city limits who have experience using forms of travel other than personal motor vehicles as their primary method of transportation." Both Ruff and Flaherty ticked through their credentials as people with experience using forms of travel other than personal cars.

Flaherty cited his personal experience using all four main transportation modes—transit, automobile, bicycling, and walking—as his primary means of getting around at different times in his life. He currently mostly walks to get around, he said.

Ruff said he'd lived for 50 years as a commuting cyclist in Bloomington, and living in an urban setting means he is a frequent pedestrian. Ruff said he had firsthand knowledge of transportation safety concerns from raising two children, using walking and bicycling for transportation.

Decisions about the permanent changes in the roadway

The choice the council made between Flaherty and Ruff—who sit next to each other on the south end of the table—came after remarks that Dave Rollo made during council report time at the start of the meeting. Those remarks set the stage for a topic that was a highlight for Ruff's remarks about why he wanted to serve on the commission.

Rollo reported that corporation council Margie Rice—who serves as head of the city's legal department—had notified councilmembers that permanent changes in the roadways like stop signs, bike lanes, greenways, speed bumps and the like, are under the control of the administration, according to state statute. Rollo said, "Now that is new to me, but apparently, that's how they're interpreting the code."

Rollo observed that such matters had previously been left to the council's discretion "as recently as just a couple of months ago, actually, when we were asked to approve the closure of Kirkwood." As a result, Rollo said, the council should no longer accept legislation about road closures. Rollo said he's happy that the 7th Street stop signs have been reinstalled, but said that the mayoral administration's interpretation of state law comes with the idea that it has to accept responsibility to make those changes. Kerry Thomson has served as Bloomington's mayor since the start of 2024.

Effort to put city council in control of greenway decisions

In his statement in support of his appointment to the transportation commission, Ruff connected to Rollo's earlier mention of the council's statutory authority. Ruff cited an effort he had made in late 2024, to amend the proposed ordinance establishing the new transportation commission. That amendment would have modified the general approach of replacing in city code all instances of "Traffic Commission, Bicycle Pedestrian," "Safety Commission," and "Parking Commission" with references to the "Transportation Commission."

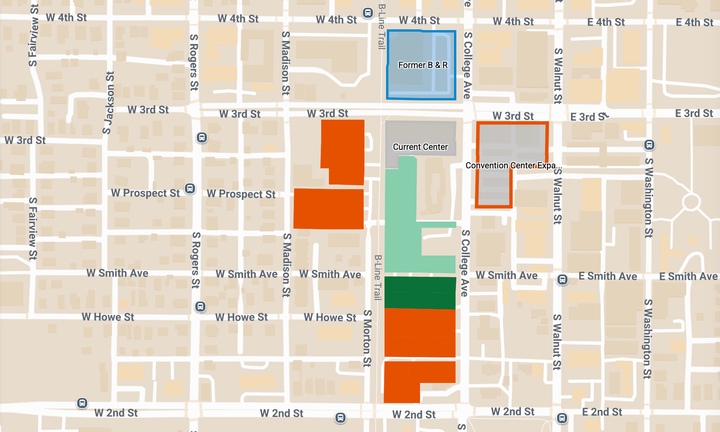

The specific place where Ruff had wanted to amend that approach was the traffic calming and greenways program. Rollo was a cosponsor of that amendment. Bloomington's city code had previously given the bicycle and pedestrian safety commission a role for the program's administration. Prompted by neighborhood opposition to the Hawthorne-Weatherstone greenway project, which was nevertheless constructed after some modifications, Ruff and Rollo were keen to give the city council final say for such projects.

The ordinance as enacted by the council had the effect of modifying code like this (emphasis added in bold):

15.26.020 Traffic calming and greenways program. The traffic calming and greenways program administered by the planning and transportation department and the transportation commission shall be incorporated by reference into this chapter and includes any amendments to the program, as approved by the common council by ordinance.

But the consideration of the transportation commission ordinance in late 2024 got postponed indefinitely, when the council ran out of time during its final meeting of the year. This year, when the ordinance to establish the transportation commission was again put in front of the council, Ruff did not try to amend the ordinance in the same way.

Apparent concession: Executive branch has control of streets

In a Jan. 30, 2025 email to other councilmembers, Ruff explained why he was not going to try to put forward the same amendment (emphasis added in bold): "You probably know that the current Administration has taken a position that Title 15 of BMC [Bloomington Municipal Code] has in the past and in certain parts likely still does include Council roles and powers that are not supported by state law." Title 15 is called "Vehicles and Traffic."

Ruff's Jan. 30 email message says that the Thomson administration's reading of state law is consistent with the council's own attorney, Lisa Lehner's—specifically in connection with the approval of traffic calming and neighborhood greenway projects. Namely, state law does not give the city council the authority to decide permanent changes to the roadway.

Given the uncertainty about the city council's role in other parts of Title 15, which includes the installation of stop signs, Ruff was not interested in pursuing the same kind of amendment that he put forward last year. Ruff wrote: "If this is in fact the case then it seems to me that the legislation coming to us that creates the [transportation commission] should not include anything that conveys approvals or oversight authority to the [transportation commission] unless and until we understand exactly what is wrong with our Title 15 and what changes need to be made to correct Title 15." Ruff voted against the enactment of the ordinance that established the transportation commission. Rollo also dissented, but it passed 7–2.

On Wednesday, before the council took its vote, Ruff faced a pointed question from his colleague, Isabel Piedmont-Smith, who asked: "How do you reconcile your desire to serve on this commission with your vote against creating the commission?"

In responding to Piedmont-Smith, Ruff essentially echoed the same sentiments expressed in his email message from two months earlier. Ruff said, "My vote was not against creating the commission at all. My vote was against creating a commission at a time when there was still this confusion about exactly what powers were being conveyed from the existing ordinance, the existing code related to Title 15, and particularly the powers of the bike safety commission."

Statutory basis for the executive as decision maker on streets

On Feb. 5, the night the council voted to establish the transportation commission, corporation counsel Margie Rice cited IC 36-9-7-5 as the basis for her conclusion that it's the city's traffic engineer, not the city council, who has legal control over what happens in the city's roadways:

Powers and duties of traffic engineer

Sec. 5. The traffic engineer shall:

(1) conduct all research relating to the engineering aspects of the planning of:

(A) public ways;

(B) lands abutting public ways; and

(C) traffic operation on public ways; for the safe, convenient, and economical transportation of persons and goods;

(2) advise the city executive in the formulation and execution of plans and policies resulting from the traffic engineer's research under subdivision (1);

(3) study all accident records, to which the traffic engineer has access at all times, in order to reduce accidents;

(4) direct the use of all traffic signs, traffic signals, and paint markings, except on streets traversed by state highways;

(5) recommend all necessary parking regulations;

(6) recommend the proper control of traffic movement; and

(7) if directed to do so by ordinance, supervise all employees engaged in activities described by subdivisions (3) through (6).

A Bloomington ordinance amendment on departmental organization was approved in 2020, and created a "Department of Engineering," without the word "traffic." The title of the state code chapter that allows a city council to create such a department is: "City Department of Traffic Engineering." And Bloomington's ordinance includes a specific reference to the chapter that allows a city council to establish a department of traffic engineering.

Bloomington city code explicitly assigns the city engineer, as director of the city's engineering department, the authority of the traffic engineer as described in the state code chapter: "The director of engineering shall possess the qualifications and shall have the authority and responsibility set forth in Indiana Code § 36-9-7." It's the same kind of authority that was given to the engineer, in Bloomington's previous departmental organization, where the city engineer was a staff member of the planning and transportation department, and reported to the planning director.

That means there's a long history of a disconnect, between the apparently limited statutory authority of the city council, and the way the council has actually exercised authority.

Remembering West 3rd Street in 2012

At the Feb. 5 city council meeting when the transportation commission was established, corporation counsel Margie Rice alluded to a controversial episode from 2012, when a stretch of West 3rd Street, between South Jackson and South Buckner, was considered for installation of speed bumps. In that case, it was not the city engineer who superseded the council's action, but rather the board of public works.

After considerable controversy, the city council finally approved the speed bumps on a 5–4 vote. But after that, the board of public works rejected the project. The Herald-Times coverage included this:

Council member Chris Sturbaum, a champion of the speed bumps, said West Third Street residents who attended the board of public works meeting were "crushed," even crying, after the board denied the petition. The neighbors, he said, believed the debate had ended with the council vote.

But the speed bumps got installed anyway, because then-mayor Mark Kruzan wanted to avoid the expense of litigation. From the Herald-Times coverage:

"There are some on the city council who had been looking at litigation, and the thought of the taxpayers paying to litigate each side of the issue didn't make sense to me," Kruzan said. "For $800 worth of speed bumps versus thousands of dollars of litigation, it just didn't make sense."

At Wednesday's meeting, Bloomington city council members Matt Flaherty (left) and Andy Ruff vie for the city council's appointment to the newly formed, nine-member transportation commission. The "New Traffic Pattern Ahead" sign alerts southbound traffic on Morton Street that the upcoming 7th Street intersection is now an all-way stop. (March 26, 2025)

Comments ()