Analysis | From transit, to climate, to basic services: A changing trajectory for Bloomington’s income tax proposal

An op-ed written by Bloomington’s mayor, Democrat John Hamilton, published Friday morning in The Herald-Times, tries to make a case for Bloomington’s city council to enact a quarter-point increase to the local income tax.

The Friday morning op-ed by the mayor resurfaced the idea of a quarter-point local income tax increase, after a six-week period of public silence on the part of city councilmembers.

That six weeks is measured from July 16, when Hamilton re-introduced the topic of a local income tax increase, after first announcing the idea on New Year’s Day—as a half-point increase.

Even if the headline to Hamilton’s op-ed reads, “We all have a decision to make,” it’s elected representatives, like city councilmembers, who will take the deciding votes.

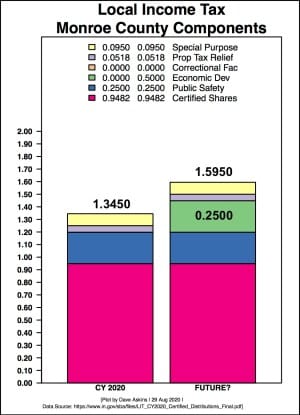

Adding a quarter point (0.25) to the local income tax rate would generate about $4 million for Bloomington and a little more than $4 million for Monroe County and Ellettsville governments.

Possible timing for the city council’s action would include a first reading at a special meeting on Sept. 9. That could be followed a week later by a second reading and final vote on Sept. 16.

Hamilton’s op-ed attempts an argument for quick city council action by raising the specter of possible future moves by Indiana’s Republican-dominated General Assembly: “The state legislature may well reduce or eliminate our ability to accomplish new revenues by next spring (they already changed the voting requirements earlier this year).”

For Hamilton, the preservation of essential government functions is an important reason for the tax rate increase. That’s based on the final sentence of his op-ed: “This prudent, proposed investment is needed to meet the daunting challenges that we face in common, and to sustain the basic services on which we all depend.”

The timing issue, when combined with one stated purposes for the tax increase, makes for a pitch that goes something like this: The city council needs to act now, in case the state legislature takes away Bloomington’s ability to pay for basic services.

Two separate issues stand out as dubious in connection with that pitch. One is the question of urgency. The other is the question of purpose.

Urgency: Statutory timeline for enactment

If the city council acts by the end of October this year, the new income tax would be effective starting Jan. 1, 2021: “An ordinance adopted after August 31 and before November 1 of the current year takes effect on January 1 of the following year.” [IC 6-3.6-3-3]

Based on the process outlined in the statute, once a majority of votes on the tax council have been cast in favor of or against a proposed ordinance, the other governing bodies on the tax council don’t need to vote on the question. The three governing bodies involved are the Bloomington city council, the Monroe County council, and the Ellettsville town council.

There are 100 votes at stake. In round numbers, the seven county councilors get 5.29 vote apiece. The nine city councilmembers get 6.44 votes. And the five Ellettsville town council members get 1 vote apiece.

If Bloomington were to vote first, and achieve the required 50+ votes, that’s where the process could stop. If Bloomington did not achieve the required majority, and it needed support from the county council or the town council, then the ordinance would go to those governing bodies for a vote.

Under the statute, if the question is not settled by the Bloomington city council, the county auditor has to give copies of Bloomington’s proposed ordinance to the county council and the Ellettsville town council. The county auditor has 10 days to deliver the copies. After getting the proposed ordinance from the auditor, the county council and the town council are required to vote on the question within 30 days.

By planning a final vote for Sept. 16, it looks like the city council would be hedging its bet, in case it does not achieve at least an 8–1 majority. If the question is still open after the Bloomington city council votes, the 40-day time span would force the other two governing bodies at least to vote on the question before the end of October. That would provide a chance for Bloomington to lobby county councilors and town councilors so that a majority could be achieved.

The statutory process looks like it prevents a scenario where there’s a 7–2 vote on the city council, and there’s one county councilor who would support it, but the other six county councilors won’t allow a vote to be put on the agenda. Under the statute, that vote has to be taken, and it has to come within 40 days of the city council’s vote.

The planned legislative pace hedges against an unlikely scenario. If the proposal doesn’t get at least an 8–1 majority on the city council, it’s not clear who on the county council might throw support behind the proposal.

The two-week timing, after city councilmembers have been quiet on the mayor’s newest proposal for six weeks, invites the criticism that the proposal is now being rushed through without any substantial public discussion.

The longer period of public engagement that was planned for the earlier half-point proposal was a casualty of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Urgency: What’s Ellington up to?

Why does Hamilton think that the 2021 legislative session could include a bill to eliminate the ability of local units to increase local income tax revenues?

According to the mayor’s communications director, Yael Ksander, that line of thinking is based on the expectations that state representative Jeff Ellington, a Republican, has for the 2021 legislative session, as described in The Herald-Times.

An Aug. 2 H-T piece by Ernest Rollins reported, “[Ellington] added the legislature will be examining how the local option income tax levies are set up, their impact on other levies and who is in charge of passing them.” The piece quotes Ellington saying, “The changes in the new tax bill didn’t go far enough to protect county residents from cities, but it did take away the block of votes as one total to dividing it down amongst city council seats.”

Ksander concluded from that news article: “That seems like a pretty significant spoiler alert re: the possibility of the legislature taking away this prerogative.”

Urgency: Sunset on voting allocations, how weights work

One objective signal of legislative intent for the 2021 legislative session is the fact that the change made this year to the individual voting allocations has a sunset clause for May 2021. It was intended to be a temporary fix, and was widely regarded as an improvement to the law, even if it’s portrayed in a negative light by Hamilton’s op-ed.

Here’s why the revision to voting allocations was acknowledged by many as a positive step. Under both the old law and the new law, the assignment of voting weights for two, but not all three, of the governing bodies in the tax council is based the proportion of the county’s population they represent.

About 58 percent of the county’s residents live in Bloomington, so Bloomington is assigned 58 out of 100 votes on the tax council. About 5 percent of the county’s residents live in Ellettsville, so Ellettsville is assigned 5 out of 100 votes.

But for the county council, the other member of the tax council, it’s not the proportion of the county’s population that is key—if it were, then all 100 votes on the tax council would belong to the county council. Instead, the county council is assigned those votes that are left over from Bloomington and Ellettsville: 37 = 100-58-5.

If each governing body’s allotment of votes is made as a bloc—that’s how it worked under the old law—then a simple majority on the Bloomington city council, five of nine city councilmembers, is enough to impose an income tax on every resident of Monroe County.

The change made during this year’s session, which sunsets in May 2021, allocates the votes to each individual member of a governing body. In round numbers, county councilors get 5.29 vote apiece. City councilmembers get 6.44 votes. And Ellettsville town council members get 1 vote apiece.

A unanimous city council can still impose a tax on all county residents. But if a proposal gets just a 7-2 majority on the Bloomington city council, then in order to pass, it would need support from at least one county councilor, or all five Ellettsville town councilors.

In sum, the change to the voting allocations mediates somewhat against the ability of a city council to impose a tax on all of the county’s residents.

Even though the legislative change came after Bloomington’s initial discussions of raising the income tax at the beginning of the year, it was not a reaction to Bloomington’s proposal. That’s according to state representative Peggy Mayfield, assistant majority floor leader for the Republicans, who represents part of the eastern side of Monroe County.

Mayfield told The Square Beacon in an interview over the weekend that the question of vote allocations had not been a “one-session issue.” Breaking up blocs of votes by assigning weights to individuals was something considered and discussed in previous sessions dating back to 2015, Mayfield said. Mayfield is a member of the ways and means committee, which would handle revisions to the statutes on local income tax.

Urgency: What’s possible, likely in 2021’s session?

As long as the county council is just part of the mix with other jurisdictions on a tax council, the county council’s share of votes won’t be commensurate with the population it represents.

The Square Beacon asked Mayfield about the idea of making the county council the one governing body that decides issues for countywide local income taxes. That would be consistent with the way countywide food and beverage taxes are decided—by the county council.

Mayfield said while anything is possible, she did not think that was likely—because there is such a long legacy of inclusion of city government in the mix. The idea is to “mitigate”—not to eliminate—the power of cities to impose a countywide income tax, Mayfield said.

The Square Beacon also asked state representative Jeff Ellington, who represents part of the southwestern corner of Monroe County, about the idea of the county council as the decision-making governing body for countywide income taxes. The representation would be equitable, he said. But about possible legislative action in 2021, Ellington said, “The likelihood is: not likely.” He added, “Cities and towns have a lot of influence,” Ellington said.

Indiana local income taxes are currently all countywide. A city does not have the option of imposing an income tax just on residents of the city. A different approach would be to provide a city with the ability to impose an income tax just for residents of a city.

It’s that possibility for the 2021 state legislative session that Monroe County councilor Geoff McKim sees as a reason for Bloomington to wait until the 2021 session is over, before voting on an income tax. A bit later the same day in mid-July when Hamilton renewed talk of an income tax increase, McKim, who’s a Democrat, wrote on his Facebook page: “I do not support an additional county-wide income tax at this time, under the existing local income tax rules (where the Bloomington city council can unilaterally impose a county-wide income tax).”

At the time, McKim pointed to possible reforms the state legislature could make that would allow a city council to impose a local income tax just for city residents, not including other residents of the county. McKim said that in the past it has not been possible, because the software used by the state does not allow for allocations to be made based on the jurisdiction inside the county where the local income tax payer lives. Local income tax distributions are currently made to the jurisdictions using property taxes as a kind of proxy, through a “property tax footprint” formula.

McKim said the state’s software is being upgraded to allow for a city layer of income tax.

Mayfield confirmed McKim’s description of the software situation. She said she is not certain if the incremental process of upgrading the software had reached a point where a cities could be separated out as a separate layer. By 2022, if not before, the system is supposed to be able to handle that, Mayfield said.

As for the likelihood that a city-only income tax could be a part of the 2021 session, Mayfield said she’s not sure. Given the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on revenues, Mayfield said, legislators will be focussed on “survival.”

Asked by The Square Beacon for his perspective, former Bloomington mayor John Fernandez (1995-2003) said, “I think the smartest, most effective policy is to enable taxing jurisdictions (whether a city, town or county) to establish rates for their jurisdiction. I don’t believe cities should be controlled by county officials any more than I think the city should be able to impose taxes on county residents simply because they have the majority vote on the income tax council.”

Fernandez’s advice for Bloomington electeds: “[Hamilton should] get out in front of this and demand that the legislature enact this legislative fix. He could get county officials on his side for once!”

County officials generally are not on Hamilton’s side with his proposal to raise the income tax. In a July 24 press release from county councilors and county commissioners, they wrote: “[W]e are concerned that [Hamilton’s] proposed 0.25 percent local income tax increase is neither necessary nor expedient given the current economic circumstances.”

One task that county officials would face is how to spend the extra money that potential city council action would generate for county government. They’d need to decide what, if anything, to spend it on.

That’s connected to some of the specific reforms for local income tax laws, that Ellington said he’s mulling for 2021. He’s thinking about ways to make explicit and list out what revenues can be spent on.

Currently the “economic development” category [IC 6-3.6-10-2] has a catch-all on the list: “any lawful purpose for which money in any of [a fiscal body’s] other funds may be used.”

What taxpayers want, Ellington said, is something they can “see, feel, touch, that they will get a benefit from.”

Purpose: Transit

The general idea of increasing Bloomington’s local income tax predates Hamilton’s New Year’s Day proposal.

Transit advocates had previously pushed the idea of expanded public transportation service, funded by an increase to the local income tax.

Hamilton’s New Year’s Day announcement described a focus broader than transit. Hamilton called for “a new annual funding source for a sustainability fund, focused on supporting mitigation and adaptation in the face of climate change, as well as climate justice and inclusion for all.”

But transit was still a key component to the plan. In Hamilton’s “state of the city” address, which came in the third week of February, he sketched out one possibility, which was to increase the annual operating budget of Bloomington Transit by 40 percent.

Leaving out the capital expenses, in round numbers BT’s annual budget can be pegged at about $9 million for the last few years. So Hamilton was proposing to spend around $3.6 million on public transit, or the better part of half of the $8 million that the half-point increase would have generated.

Besides transit, other components of the possible sketch from the “state of the city” address included affordable housing investments, clean energy supports, and local food support.

During the city council’s budget hearings in the third week of August, BT general manager Lew May talked about the possibility of increased transit funding. It came up in response to a question from councilmember Kate Rosenbarger about the possibility that BT would in the future adopt a fare-free approach to ridership.

May said, “Over the years, there’s been a lot of discussion about that, especially at council budget meetings just like this one. We’re very open to the possibility of going fare-free. All we need is for somebody to step to the plate and provide the funding to replace the funding that we would lose.”

In his budget presentation, May said, “There have been discussions in the past year about the possibility of a climate LIT [local income tax], …a portion of which could be used for expanding public transit service in our community.”

May added, “I know those conversations have taken a backseat in response with the onset of the pandemic, but we’re hoping that those conversations will resume at some point and that there’ll be some serious consideration given to using a climate LIT to possibly expand public transportation and grow it and improve service in our community.”

Purpose: Not transit

With Hamilton’s proposed reduction of the rate increase—from a half to a quarter point—came the virtual elimination of increased transit funding.

During WFIU’s Noon Edition on Friday, Hamilton said, “I have to say the transit system is in such tumultuous times that—how many people are riding it in their future?… So if you pull that half out [that would have gone to public transit], that leaves 0.25, which I still believe is a very important investment to move us in these directions.”

As a reason not to include funding for public transit in the 0.25 proposal Hamilton also cited the $7.8 million CARES Act grant that BT had received from the federal government. Those grants are meant to make up for the impact of COVID-19 on public transit.

The mayor’s communication’s director, Yael Ksander, confirmed to The Square Beacon, that public transit is not a significant part of the new 0.25 local income tax proposal: “[T]he new reduced LIT would not include much transit funding, except a small amount for bus stops.”

It’s not clear what specifically would still be in the mix for the 0.25 proposal.

On New Year’s Day, Hamilton called for the creation of a “green ribbon panel” that would help “identify and support local efforts to address climate change, to mitigate and adapt.” It’s not clear if the panel was ever created or what recommendations it made.

Purpose: Basic services?

The kick-out to Hamilton’s Friday op-ed in the Herald-Times puts “basic services” into the mix of things the tax increase was needed to pay for.

A local income tax increase was not a part of the 2021 budget proposal put forward by Hamilton two weeks ago. Councilmembers did not discuss the possibility of a local income tax increase during their budget hearings.

The 2021 budget proposal included drawing down reserves, as part of a two-year plan. Over two years, the idea is to reduce the city’s reserve level from the current level of four months’ worth of operating reserves. By the end of 2022, the city would have to three months’ worth of operating reserves. That means using a total of $8 million in reserves, spread across two years, according to Hamilton’s plan.

Of the $8 million in reserves, $4 million—$2 million each year—is supposed to be used to avoid lay-offs and sustain essential operations. The other $4 million—also split evenly over two years—would be used to help accelerate community and household recovery and to “reduce the pain and damage of the pandemic,” according to Hamilton.

Given the wording of Hamilton’s op-ed, it’s not clear if reserves alone are thought to be adequate to sustain basic services, or if the increased local income tax will at least in part be tapped for that purpose.

What’s next?

Reportedly, Hamilton will address the city council at its Sept. 2 meeting. And he’ll ask that councilmembers schedule a special meeting for Sept. 9 to hear a first reading of the ordinance that would increase the local income tax by 0.25 points.

Comments ()