Appeals judges press attorneys in Bloomington annexation on “urbanized” test, property owner best interests

Bloomington’s effort that began in 2017 to annex several territories into the city continued on Tuesday in front of Indiana’s court of appeals. For a total of about 40 minutes on Tuesday morning, a three-judge panel quizzed the attorneys for Bloomington and for annexation opponents.

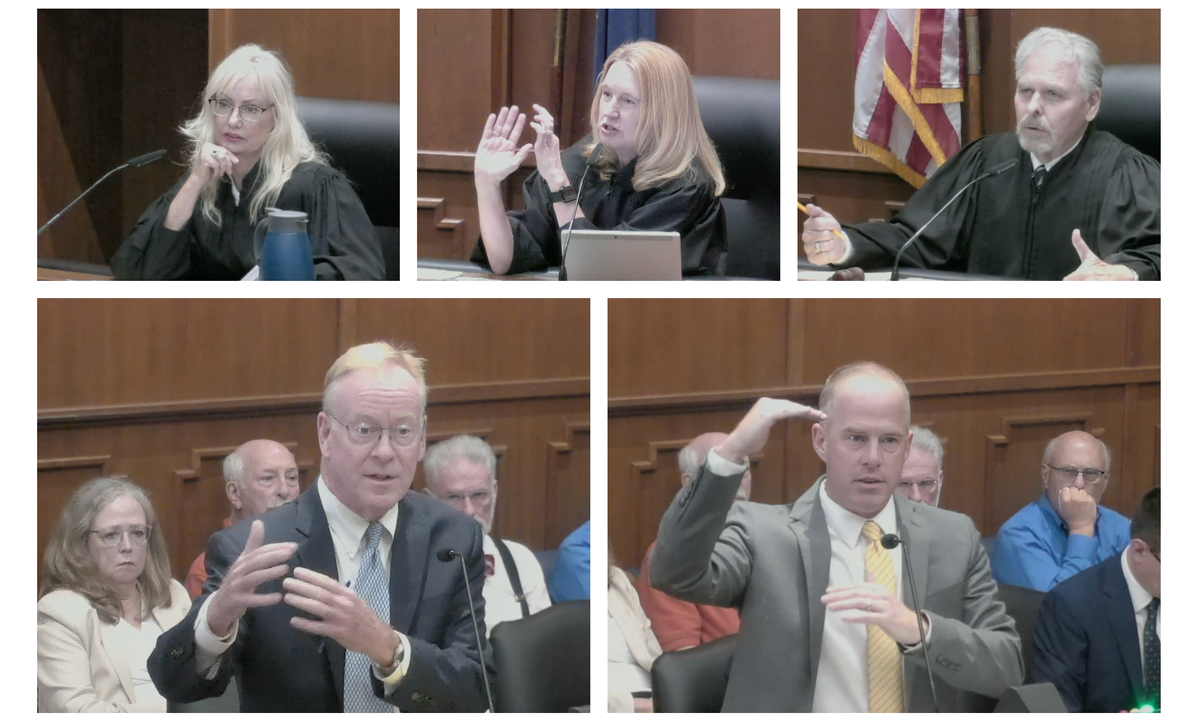

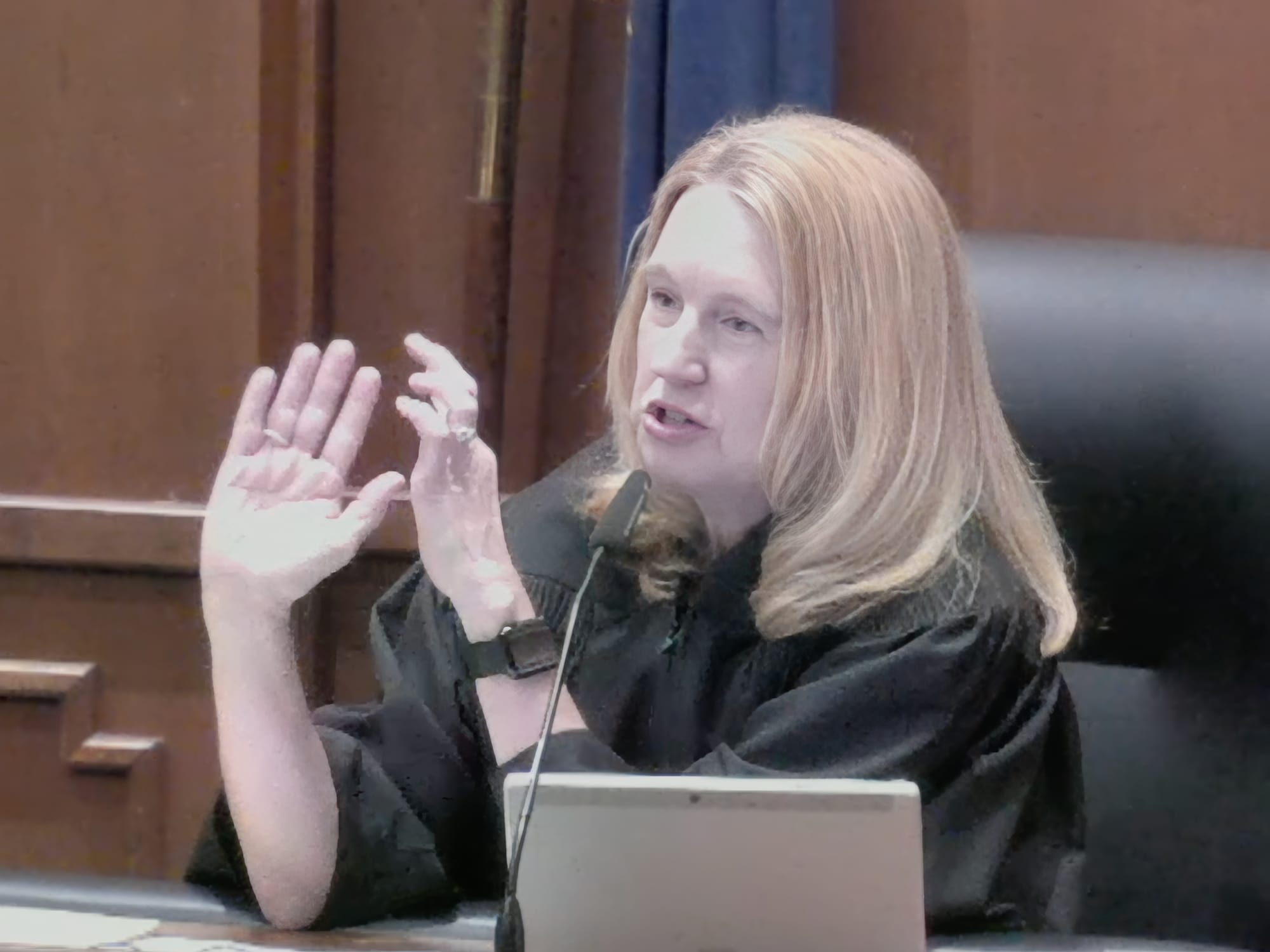

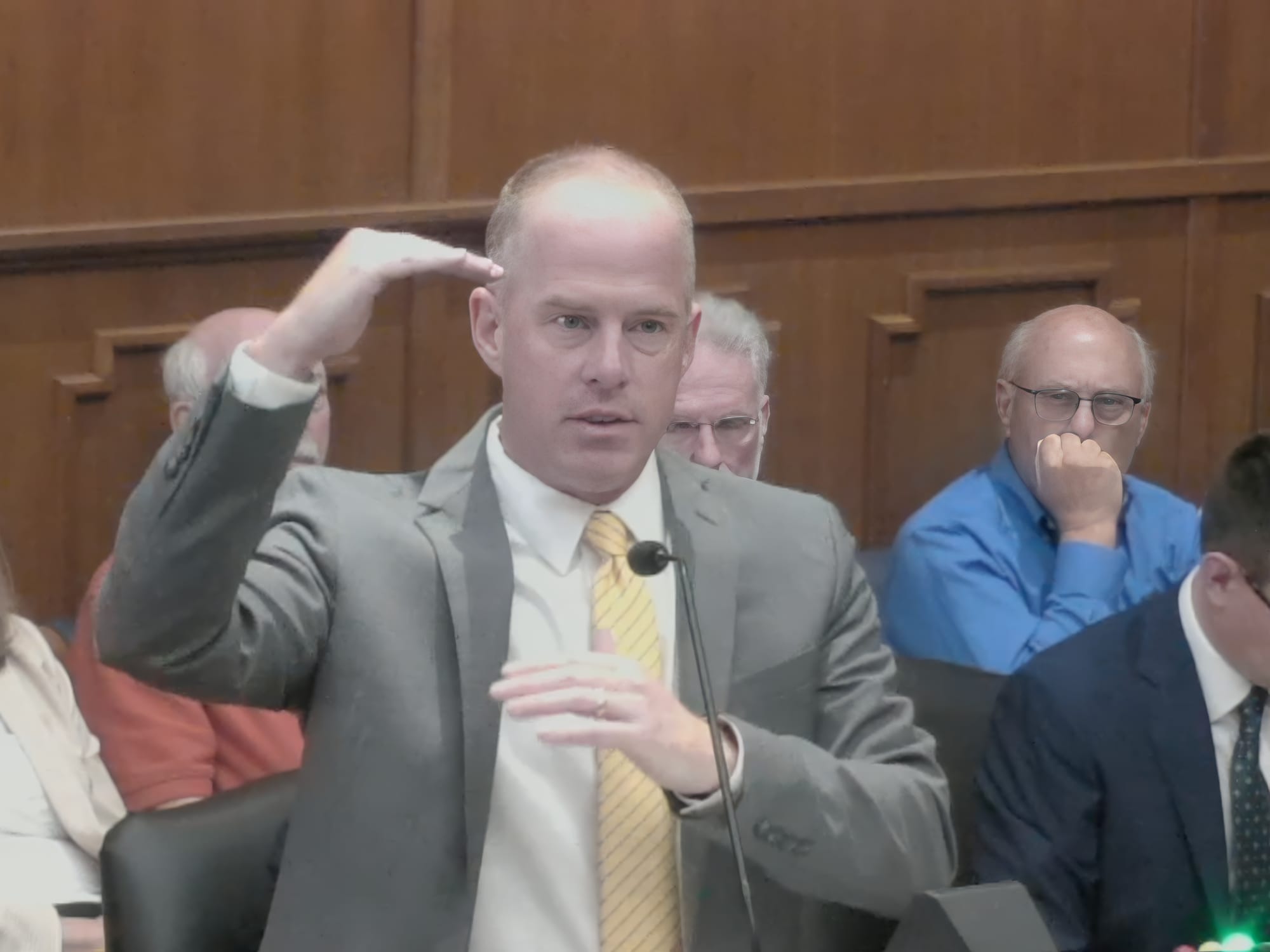

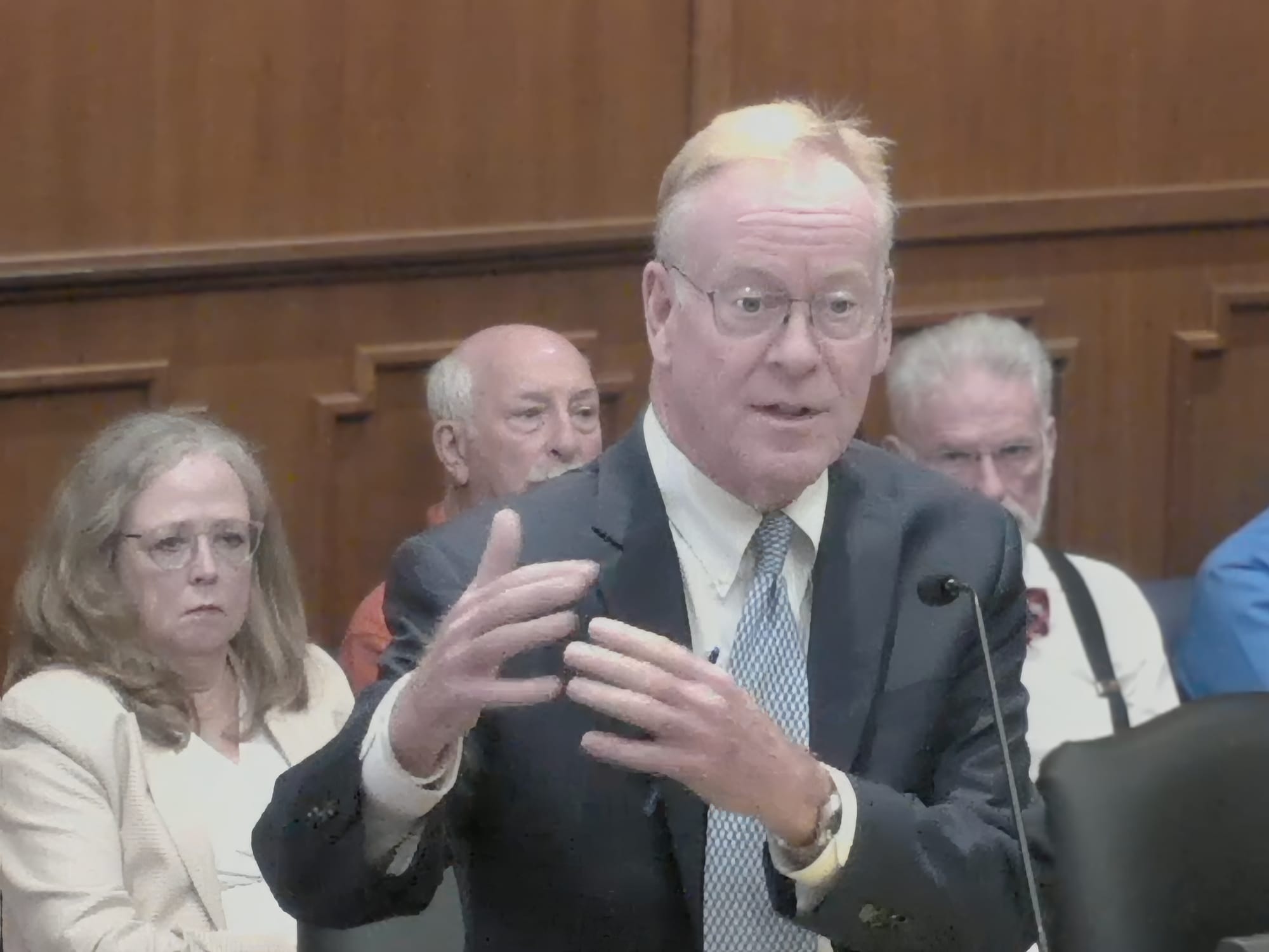

Top row from left: Judges Elaine Brown, Mark Bailey, and Leanna Weissmann. Bottom row: Outside counsel for Bloomington, Stephen Unger, and attorney for the remonstrators, William Beggs. (The screen grabs are from court of appeals video.)

Bloomington’s effort that began in 2017 to annex several territories into the city continued on Tuesday in front of Indiana’s court of appeals.

For a total of about 40 minutes on Tuesday morning, a three-judge panel quizzed the attorneys for Bloomington and for annexation opponents.

The areas of focus for this case are known as Area 1A and Area 1B.

The three judges were hearing oral arguments in Bloomington’s appeal of the lower court’s ruling, about a year ago, that Bloomington had not met the statutory requirements to annex the two areas.

It’s a trial on the merits of annexation, a proceeding made possible by the fact that more than half of property owners in the areas formally protested the city’s annexation. But the percentage of property owners who remonstrated fell short of 65%, which would have stopped the city’s annexation outright.

Arguing the city’s side on Tuesday was Stephen Unger with Bose McKinney & Evans. The city’s online financial records show that in connection with annexation issues, the law firm has been paid about $1.9 million since 2017, when the city’s annexation efforts started. That includes about $960,000 since January 2024, when current Bloomington mayor Kerry Thomson took office.

Arguing the side of remonstrators was William Beggs, with Bunger & Robertson, which has submitted legal fees in connection with the favorable ruling that was given by the lower court amounting to about $275,000.

The judges hearing the case were Elaine Brown, Mark Bailey, and Leanna Weissmann.

The basic issues in front of the court were whether the area to be annexed met one of the statutory requirements for: population density; percentage of area that has been subdivided; or zoning for commercial, business, or industrial uses.

The other big issue that will confront the three-judge panel is whether the annexation is in the “best interest” of the property owners.

Hybrid approach to criteria?

Leading off was Unger in support of the city’s position, that judge Nathan Nikirk’s ruling was wrong—because he had generally misinterpreted Indiana’s annexation law. Unger said the lower court had “strictly construed” the state law against Bloomington, in a way that contradicted the whole point of the statute and subsequent interpretations by the courts, which was to allow the annexation of areas adjacent to cities that are urbanized.

Interrupting Unger almost immediately was Weissmann, who asked him how it is known that the lower court “strictly construed the statue against the city.” Unger replied: “It says it right in the order,” and gave the paragraph number.

Here’s the part of Nikirk’s order to which Unger objected (bold added for clarity):

143. The words “urban” and “urbanized” do not appear in I.C. 36-4-3-13. Thus, the focus of the Court’s analysis is not on a subjective determination of whether a territory proposed for annexation is “urban” or “urbanized.” Rather, the analysis focuses on the objective criteria outlined in I.C. 36-4-3-13(b).

144. Further, the legislature did not direct the Court to parse between “urban” and “suburban.” Only elements constituting “urban” are contained within the statute.

145. The statute is clear on its face that the territory proposed for annexation must satisfy one of the specified conditions. The statute does not authorize a “hybrid approach” for satisfying these conditions and must be strictly construed. This Court may not ignore the requirements of the statute.

Unger said that the way the lower court had interpreted the statute is contrary to the “goal” of the state’s law on annexation. Unger said, “[T]he purpose or the goal or the object of Indiana’s annexation statutes is to permit the annexation of adjacent urban territory. That’s how we’re supposed to read and apply the statute.”

Weissmann told Unger: “You advocate a position where we should do a hybrid approach, or we should adopt a hybrid approach.” She asked him: “How do we square that with what the statute actually says?”

Uger replied: “The statute doesn’t say we have to read these [three criteria] in isolation. … The statute gives three different alternatives, but it doesn’t say we have to read those in silos.”

For his part, Beggs, arguing for the remonstrators, was in agreement with the lower court, that the phrase “the territory” had to be understood to mean the whole territory to be annexed, not just part of it. Beggs put it like this: “We can’t do any … amount of mental gymnastics to make ‘the territory’ actually mean ‘a portion of the territory,, ‘a section of the territory,’ ‘some of the territory.’ That’s what the city argues and urges you to adopt here.”

Best interest of property owners?

Even though the issue of remonstrance waivers was not in front of the court for a decision on Tuesday, they did come up in the context of the question of what is in the best interest of the property owners.

Several of the property owners, either current or past owners, had signed waivers of their right to remonstrate against annexation, in exchange for city sewer service. But a 2019 law passed by the state legislature voided older waivers.

The city of Bloomington filed a lawsuit arguing that the 2019 law was unconstitutional, and that case is now set for oral arguments in front of the Indiana Supreme Court in late October.

Judge Nathan Nikirk had originally put off conducting the trial on the merits of annexation, until the constitutional question was settled. That was because if the city prevailed in the constitutional lawsuit, the trial on the merits would have been moot. There would not have been enough remonstrance signatures in Area 1A and Area 1B to meet the threshold for a trial on the merits of Bloomington’s annexation. The city of Bloomington decided to waive the constitutionality argument for Area 1A and Area 1B, in order to move ahead with the trial on the merits.

On Tuesday, judge Mark Bailey asked Beggs about the number of remonstrance waivers that had been signed, independent of whether they would be determined valid by Indiana’s supreme court.

Baily’s question for Beggs came after Beggs pointed to the fact that several property owners had testified during last year’s trial on the merits—saying that annexation was not in their best interest. Beggs characterized the city of Bloomington’s position as meaning that “competent adults should not be listened to by trial judges when they … go to court and testify in an annexation case.”

Responding to that statement from Beggs, Bailey said: “I want to know how we should take the fact that a lot of these land owners did sign waivers in order to get the services that they now don’t want to pay for. How does that weigh into the best interest?” Bailey added, “Because it seems to me that if you’re signing a waiver in exchange for sewers, you feel it’s in the best interest that you have these services from the city.”

Joining in Bailey’s basic point was Weissmann, who put it like this: “Like my grandma used to say, you want to have your cake and eat it, too.”

By way of response, Beggs pointed out that sewer service is, in fact, funded by rate payers themselves. The cost of sewer service for non-city residents is 12% more than for city residents, Beggs noted. He told the three-judge panel: “The court heard that evidence, knew that evidence, and still concluded that is in their best interest not to be annexed by the city of Bloomington.”

Bailey wrapped up Tuesday’s hearing by saying “We’ll have an opinion for you as soon as we can.”

Comments ()