Bethel AME church now historic district, more Bloomington sites key to Black history could be next

On a unanimous vote by Bloomington’s city council on Wednesday, the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal church was designated as a historic district.

The 1922 church, which sits on the northeast corner of 7th and Rogers streets on the western edge of downtown, was designed in the classical revival Tudor style by John Nichols.

But the church qualifies for historical designation based on more than just its architectural significance. It also qualifies under criteria that include the cultural and historical significance of a site.

During public comment time, Elizabeth Mitchell told the city council, “This is just the beginning for me—a personal journey to make sure that we don’t forget African American sites. This is just one of them.”

Mitchell introduced herself as a historian for Monroe County on African American experience. She also serves on the city’s historic preservation commission.

Giving the presentation to the city council on the proposed district was Bloomington historic preservation program manager Gloria Colom Braña.

According to Colom Braña’s written report, the church has served as one of the main religious institutions for Bloomington’s Black community since the time the congregation was founded. Colom Braña’s report says, “[T]he church doubled as a social cultural unifier, providing a space for creativity, social cohesion, and a place where Indiana University’s Black students could find community as well.”

Confirmation that the church continues to provide a sense of community came during public commentary from Nicole Bolden, who is familiar to the council in her role as the elected city clerk. “Bethel AME and Second Baptist have been a big part of my life in Bloomington,” Bolden said.

Bolden described to the council how she’d attended an event that same evening for incoming Indiana University students. At that event, the importance of Bethel AME and Second Baptist to the Black community had been described, Bolden said. Incoming students had been reminded that they can go to those churches and find community there. Bolden wrapped up her remarks by saying, “So thank you for making sure that we will always have a place here.”

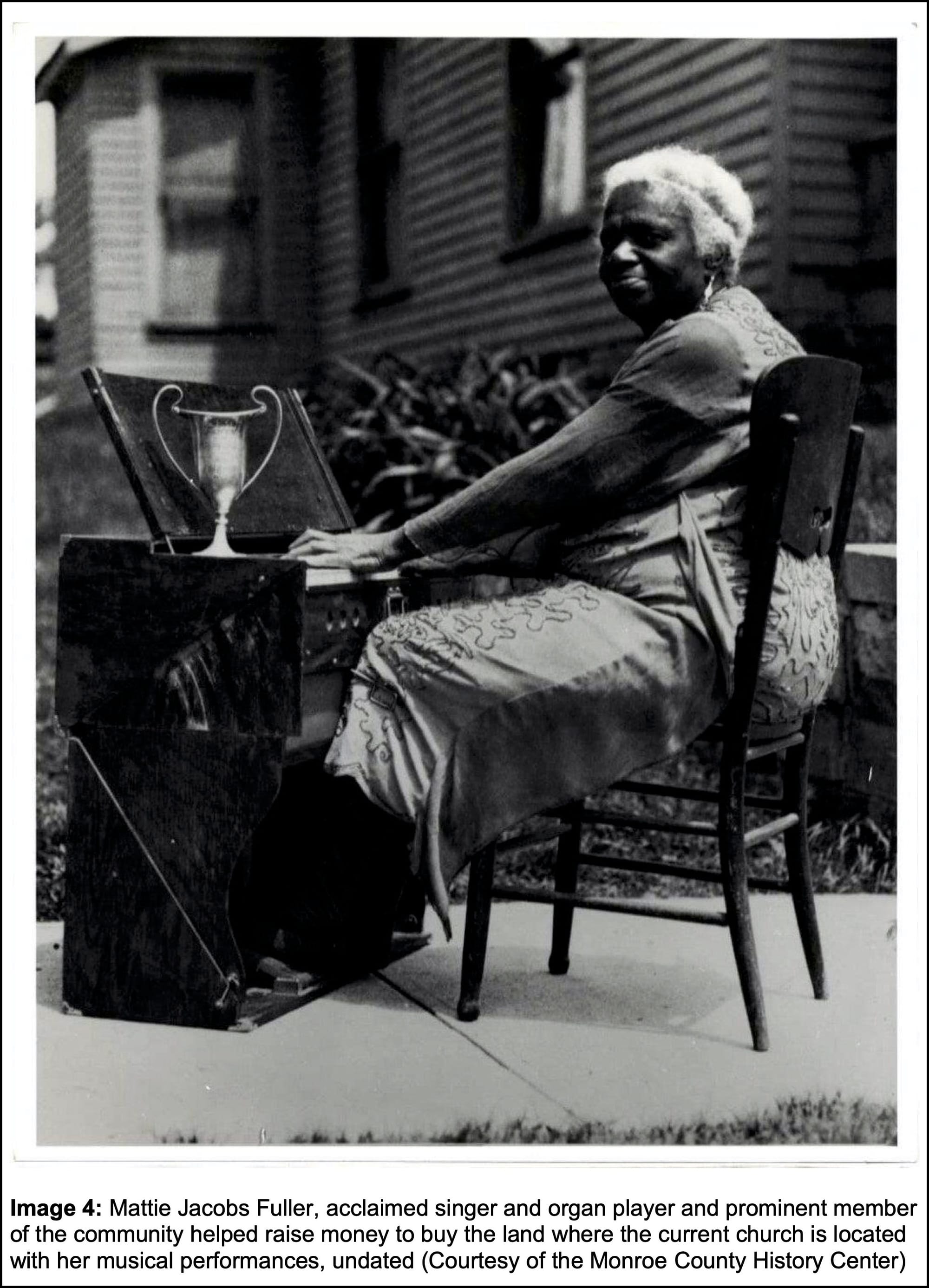

Piquing councilmember Dave Rollo’s interest on Wednesday was the possibility of tracking down an interview done in the 1930s with Mattie Jacobs Fuller, a founding member of Bloomington’s Bethel AME church. Fuller gave performances—singing and accompanying herself on a portable organ—that raised several thousand dollars to support the church’s building effort.

Colom Braña had mentioned in her remarks to the city council that she had not found a recording of Fuller’s singing voice. But Colom Braña said Fuller had been interviewed by a fieldworker with the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA’s) Federal Writers’ Project.

At least some of that interview appears to have been transcribed as part of a book published in 2000 by Indiana University Press: “Homeless, friendless, and penniless: the WPA interviews with former slaves living in Indiana”—a work compiled by Ronald L. Baker. The book is part of the Monroe County Public Library’s collection. The call number is IND R 975 Hom—the “IND R” stands for “Indiana Room.”

Fuller’s chapter in the book is called, “I have sang myself to death.” The full quote from Fuller goes like this:

I have lived in Bloomington forever. I have played and sang. I have sang myself to death. I have brought in $12,000 for my church. I would go places and play on my organ and sing. The white folks would crowd around and give me money for my church.”

The interview also gives a glimpse into Fuller’s character:

When anyone asks me my age, I say, “Never you mind,” and when they ask me how big a girl I was at the time of the Civil War, I say, “Never you mind.”

On Wednesday, Mitchell told the council that there are additional historical sites, important for the history of Bloomington’s Black community, that she wants to see formally designated.

At a mid-July city council work session, Mitchell had sketched out some of her projects, which include recording oral histories. One of the additional sites she mentioned for future historic designation was a rooming house run by John Mayes, at 418 E. 8th Street, which offered a place to live for Black students at Indiana University.

The count of Bloomington residents conducted by the US Census Bureau in 1950 reflects at least 16 “roomers” at the 8th Street address.

After Wednesday’s meeting, Mitchell told The B Square the Mayes rooming house was relatively better documented, because future NFL football player George Taliaferro had lived there. But there were several other rooming houses for Black students, she said, because they were not allowed to live on campus.

1950 US Census (Bloomington, Indiana)

Comments ()