Bloomington annexation trial a slog in first 2 days, judge warns he could require Saturday session

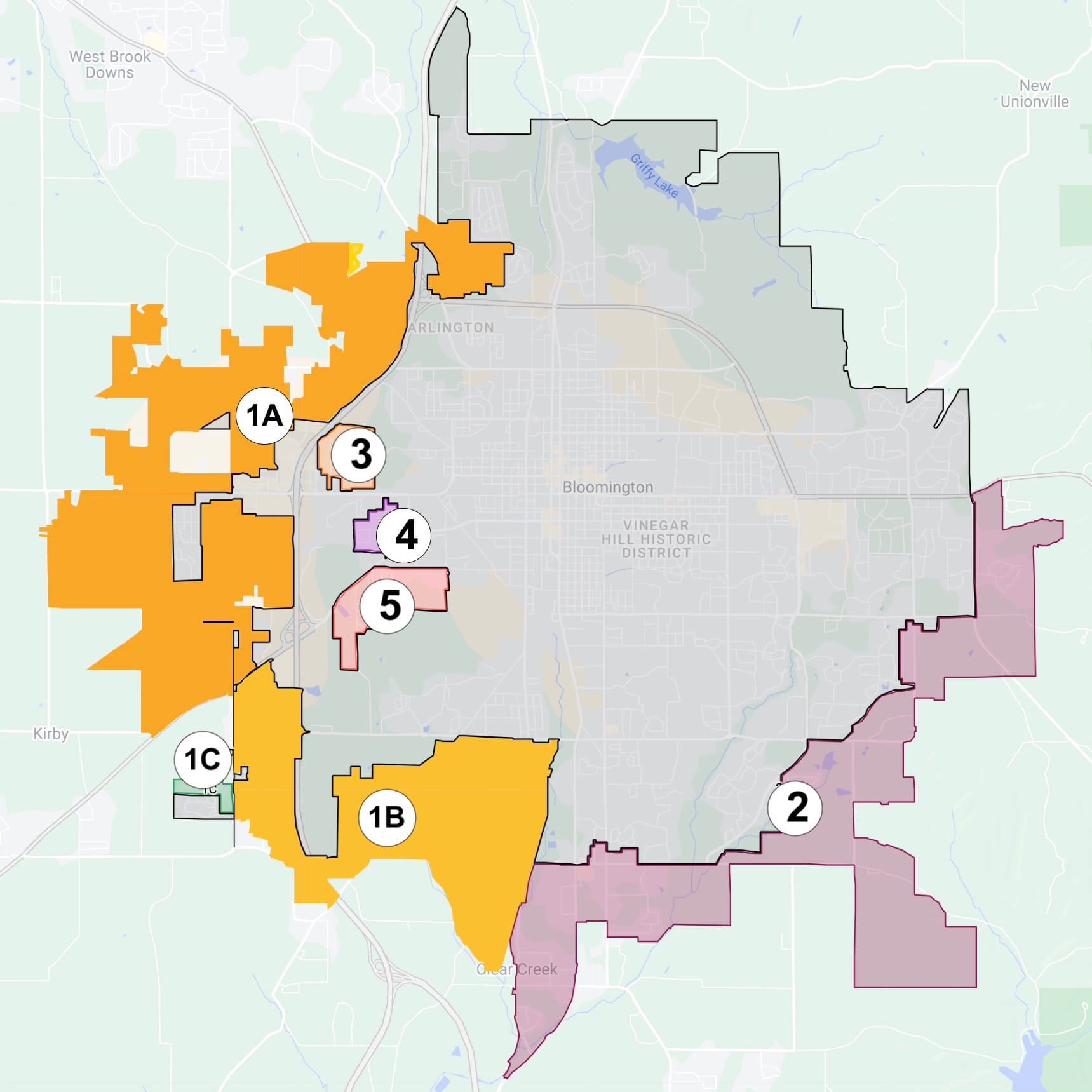

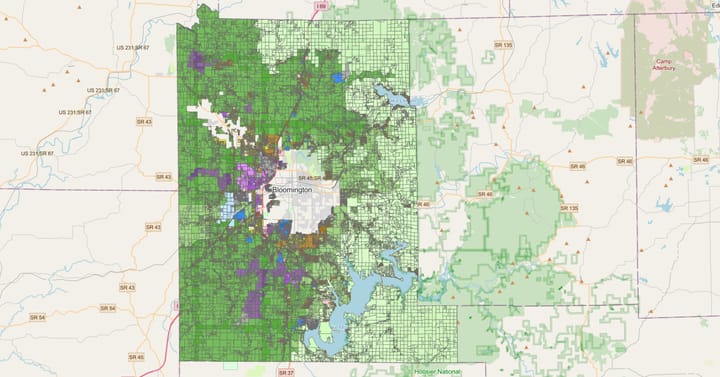

The trial on the merits of Bloomington’s plan to annex two areas on the west and southwest sides of the city has now completed two days worth of testimony.

Every day this week is scheduled for the trial. The pace so far looks like it’s slower than expected. It could be a challenge to complete the trial by the end of the week.

About the prospect that not all the witnesses on both sides might get their turn by the end of the day on Friday, judge Nathan Nikirk on Tuesday afternoon made clear that he is not keen to “bifurcate” the proceedings. He told the legal teams for both sides to be ready to come into court on Saturday to finish things off, if that’s what it takes.

On Monday, opening arguments were given on both sides, with Andrew McNeil of the Bose McKinney & Evans law firm making the presentation for the city of Bloomington, and William Beggs of Bunger & Robertson representing the remonstrators.

The proceeding is a judicial review, which was forced by remonstrators, when they achieved the threshold of at least 51 percent of landowner signatures in Area 1A and Area 1B, but fell short of the 65 percent that would have stopped Bloomington’s annexation outright.

The standards for the judge to consider in determining whether to let the annexation go ahead are laid out in IC 6-4-3-13, which is covered in Bloomington’s pre-trial brief.

The city of Bloomington is going first with its set of witnesses. Bloomington led off on Monday with former mayor John Hamilton, followed by former director of utilities, Vic Kelson, and current director of public works, Adam Wason. Monday concluded with partial testimony from GIS coordinator, Meghan Blair.

On Tuesday morning, it was not Blair but David Rusk who appeared on the witness stand. Rusk is a Washington, DC consultant and author of the popular book “Cities without Suburbs.”

The city’s examination of Rusk took most of the day on Tuesday. His biography took 45 minutes to introduce. That friendly interrogation revealed his service as mayor of Albuquerque, New Mexico, from 1977 to 1981, how he wooed his now wife of 62 years by minoring in Spanish at UC Berkeley, and the fact that he is the son of former United States Secretary of State Dean Rusk.

Rusk said under cross examination that he was being paid $30,500 for his work analyzing the history of Bloomington’s growth. Since 2017, when Bloomington launched its annexation effort, Bose McKinney has been paid more than $1.18 million for the firm’s annexation-related work.

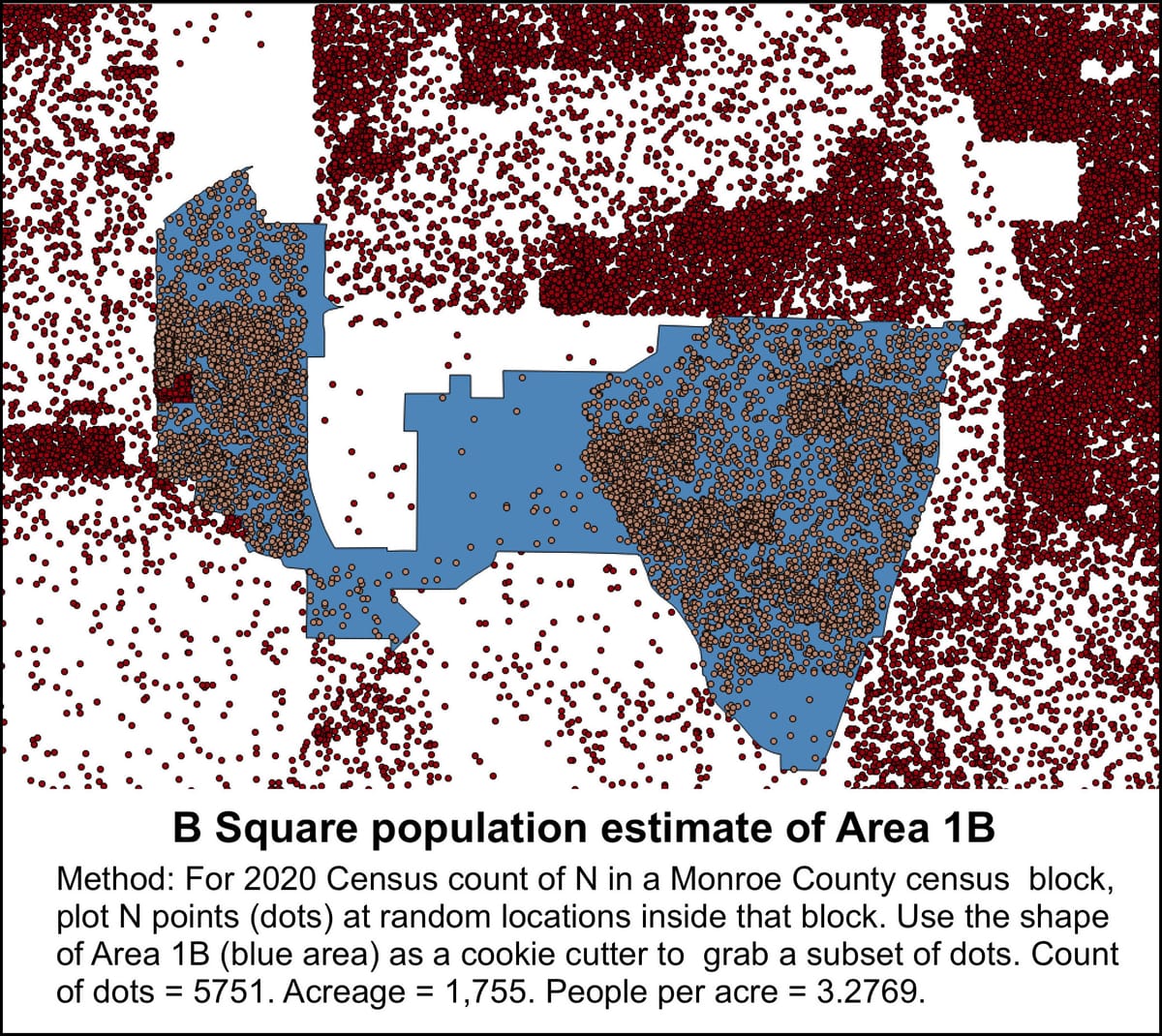

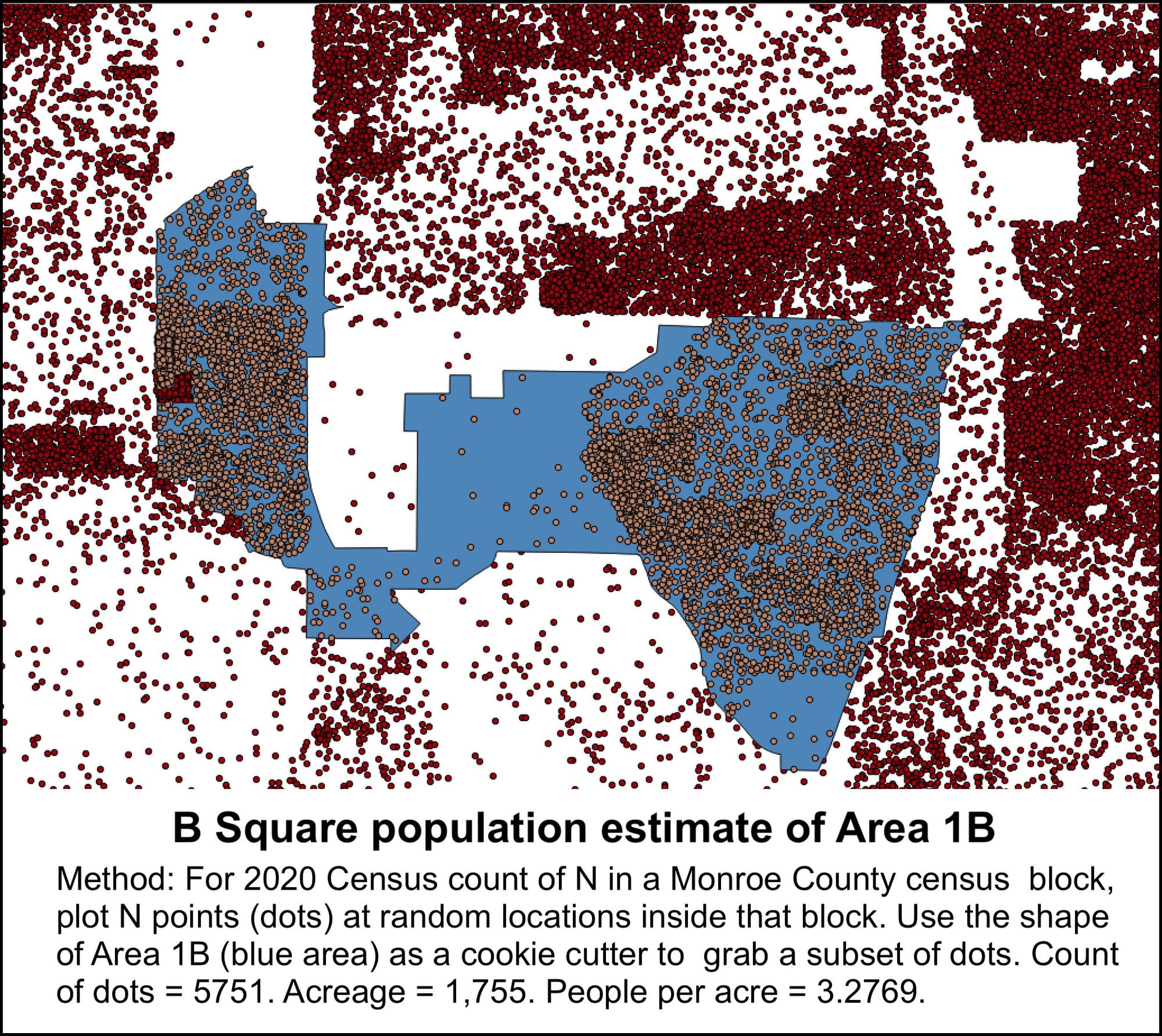

Finishing the witness lineup on Tuesday was Bloomington’s GIS coordinator Blair. She gave some testimony that was a bit of a surprise for anyone who has been tracking the annexation process since it got restarted in 2021: Blair pegged the population density of Area 1B as 3.28 people per acre.

That’s bigger than the 2.6 people per acre for Area 1B that can be calculated from a FAQ that was posted on the city’s website in 2021, as the city restarted its annexation effort. In the FAQ, the land area of Area 1B is listed as 1,755 acres, with an estimated population of 4,566, which works out to 2.6 people per acre.

Under state law, 3 people per acre is a population density for annexation territory that has special significance. If the density is greater than 3 people per acre, Bloomington can check one of the boxes that allows it to satisfy some of its burden of proof in the judicial review. The 3-person-per-acre density is not required—there are other ways to meet the burden of proof about urbanization. The 3-person-per-acre density is sufficient to satisfy part of the city’s burden, but does not end the trial.

Under state law, the key question that the judge will have to weigh is whether annexation is in the best interest of the owners of land in the territory to be annexed.

The acoustics in the courtroom make it a challenge to hear any of the key actors—judge, attorneys, or witnesses. But it sounds like the new number for the population density in Area 1B stems from the difference between American Community Survey data, which Blair’s predecessor might have used to compute the estimated population, and the actual 2020 census data.

On cross examination of Blair, Bunger & Robertson’s Ryan Heeb drew out the fact that the population in census blocks, which are the smallest geographic areas counted in the decennial census, do not necessarily have uniform population distributions.

The evenness of the population distribution in a census block is relevant to the challenge of calculating the population of Area 1B—because some census blocks are only partially included in Area 1B. For a census block that is half in Area 1B, but half outside of Area 1B, the question is how to allocate that block’s population to Area 1B.

One approach would be to assume uniformity of the population distribution and assign half of the block’s population to Area 1B. If one-third of the area of a census block is included in Area 1B, then on the same approach, one-third of the block’s population would be counted for Area 1B.

To check the city’s number, The B Square did not assume that the population distribution of a census block is perfectly uniform, but instead assigned everyone counted in a census block a random location within the block. For a 2020 census count of N in a Monroe County census block, N points (dots) were plotted at random locations inside that block.

The shape of Area 1B was used as a “cookie cutter” to grab a subset of dots. The count of dots was 5,751. When spread across 1,755 acres, that works out to an estimated population density of 3.2769 people per acre, which matches Bloomington’s number, when rounded to the nearest hundredth.

The B Square also considered just those census blocks that are wholly contained within Area 1B, without including any census blocks that are only partially included. On that approach, the population count was 5,497 people. That number, when spread across 1,755 acres, works out to 3.1322 people per acre. So the population of Area 1B looks like it’s at least 3 people per acre by a direct count of the census, with no assumptions required about evenness of population distribution in census blocks.

So far, Judge Nikirk has had to rule on several objections, from both sides. The most common kind of objection has been for “hearsay.”

The first objection came when attorney for the remonstrators, Beggs, wanted to get into the record the fact that a city consultant’s report had recommended adding sworn police officers.

Arguing for the city, McNeil said that the Novak report is not a business record of the city, because it had not been prepared by city of Bloomington personnel. Beggs, arguing for the remonstrators, said the report was commissioned by the city, which means that it is the city’s own document, a city report, and a public record. Beggs said that the report was relied upon by the city, and city taxpayer dollars had paid for it. Nikirk did not allow Beggs to pursue that line of questioning.

Beggs objected to some testimony from Rusk, who stated that “Annexation is in the socio-economic best interest of the region, including Area 1A and Area 1B …”

Beggs objected, based on the idea that Rusk was commenting on the “ultimate issue” in the case, which is for the judge to decide, namely whether the annexation is in the best interest of the landowners in Area 1A and Area 1B.

McNeil argued that Rusk could comment on the “ultimate issue” based on a rule of evidence that says: “Testimony in the form of an opinion or inference otherwise admissible is not objectionable just because it embraces an ultimate issue.”

Beggs countered that the rule has a second part that says (emphasis added in italics), “Witnesses may not testify to opinions concerning intent, guilt, or innocence in a criminal case; the truth or falsity of allegations; whether a witness has testified truthfully; or legal conclusions.” Both sides cited some cases that Nikirk said he would read over the lunch break.

When the trial resumed after lunch, Nikirk said that because it’s a bench trial—there is no jury—he would allow the kind of statement that Rusk had made, and weigh it as he deemed appropriate.

A ruling from Nikirk ended one answer that Rusk started to give, because he started talking about what a vice president of Indiana University had told him. When Beggs objected that it was hearsay, McNeil gave an argument that had been successful earlier in the day—that there’s a rule of evidence that says: “An expert may base an opinion on facts or data in the case that the expert has been made aware of or personally observed.”

But Nikirk told McNeil he needed to establish some foundation—Rusk had not named the vice president. McNeil was able to get Rusk to describe the vice president’s responsibilities—they were related to housing and facilities—but could not remember what the person’s name was. Nikirk sustained the objection.

Up for Wednesday are several more witnesses for the city of Bloomington, which will likely include current mayor Kerry Thomson at some point.

Comments ()