Bloomington annexation update: Briefs now filed by both sides in appeal of case on the merits

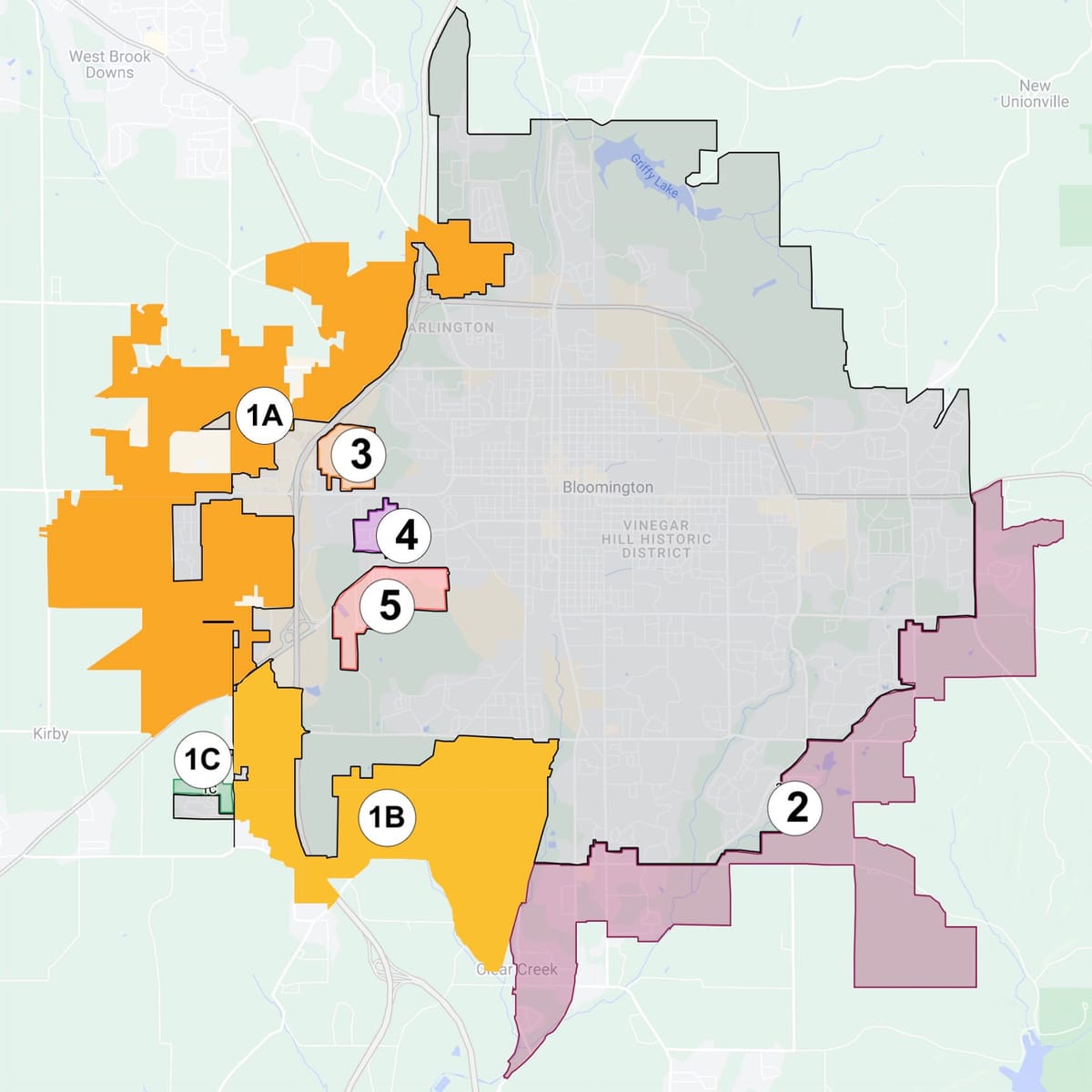

The initial briefs have now been filed by both sides in Bloomington's appeal of special judge Nathan Nikirk's ruling last August, that the city's attempted annexation of Area 1A and Area 1B could not go forward.

The case involves the merits of annexation in those two areas, not the constitutional question that has been raised for the other five areas that Bloomington wants to make a part of the city.

For Area 1A and Area 1B, remonstrators collected enough signatures from property owners to force a judicial review, but not enough to stop annexation outright.

Bloomington's brief was filed in mid-January. The response to Bloomington's brief came this past week. Both sides got extensions of time to file their arguments with the court. Under the rules of procedure for Indiana's Court of Appeals. Bloomington would have 15 days from March 19 to file a reply to the response from the remonstrators. After that, a date for oral arguments could be scheduled.

The basic arguments in the briefs don't offer any surprises. Bloomington says that the trial court made a mistake by not allowing the annexation of adjacent urban areas, because the territory is highly developed and already benefits from Bloomington's services. The remonstrators say that the trial court was right in deciding that Bloomington did not satisfy the legal requirements for annexation.

[copy of Bloomington's Jan. 17, 2025 brief]

[copy of remonstrators' March 19, 2025 brief]

What specifically do the briefs say?

Urban character

Bloomington says the annexation territories qualify as "urban" under IC 36-4-3-13(b)(2) because they have a mix of residential and commercial, business, or industrial (CBI) uses, reflecting their development as an extension of the city. Bloomington says that is the point of annexation law—to allow the annexation of urban land adjacent to a city into the city itself.

The remonstrators contend that Bloomington's "urban character" argument doesn't go through, because it did not meet the specific individual requirements of the state statute for: population density; subdivision; or CBI zoning. The statute requires meeting one of the individual conditions, not some "hybrid approach" to those conditions, according to the remonstrators' brief.

Urban character: Population density

Bloomington points to the population density of the territory to be annexed as meeting the three-people-per-acre standard, citing data from the 2020 census for Area 1B. For Area 1A, the city shows a table breaking down the territory's residential parcels, to arrive at a population density of 4.24 people per acre for such residential parcels. But the same table shows a population density of 1.38 for all of Area 1A.

The remonstrators' brief points to Bloomington's own information, published on its website and in the annexation fiscal plan, which showed that Area 1A did not meet the three-people-per-acre density requirement. For Area 1B, remonstrators say the trial court was not persuaded by Bloomington's GIS coordinator's new calculations, which showed a population density of 3.8 people per acre, which were based on the 2000 census numbers, but came about two years after the Bloomington's annexation ordinances were approved.

The newer calculations were not included in the information about annexation in public notices. In its published information about the annexation before the ordinances were passed, the population density for Area 1B was given by the city was 2.60 people per acre, remonstrators point out.

Urban character: Subdivisions, Zoning

Bloomington contends that at least 60% of the territory is subdivided, demonstrating its urban character. Bloomington also notes that a high percentage of parcels are smaller than one acre.

On this point, the remonstrators say that the precedent of a 2019 case involving the Town of Brownsburg requires the city to demonstrate that at least 60% of the acreage is within formally recorded residential subdivisions, not just 60% of the number of parcels. Bloomington did not provide evidence of the total acres in formally recorded residential subdivisions, according to the remonstrators.

The brief filed by Bloomington says that the significant commercial, business, and industrial (CBI) zoning in the annexation areas further supports its urban character under the state annexation law.

On this point, the remonstrators say that neither Area 1A (at 57.69% CBI) nor Area 1B (at 29.56% CBI) meets the statutory requirement, under a precedent established by a 1997 case involving the City of Elkhart. According to the remonstrators' brief, an "overwhelming majority" (over 93%) of the territory has to be zoned CBI. Remonstrators say the trial court correctly applied the plain language of the statute on the question of urban character and rejected Bloomington's "hybrid" approach to satisfying that part of state law.

Bloomington's 'need' for the areas proposed for annexation

Bloomington contends that the city needs and can use the annexation areas for its development in the reasonably near future, particularly to address the affordable housing crisis in Bloomington and Monroe County. The Monroe County government has rejected housing developments in the proposed annexation areas, according to the city's brief.

On this point, the remonstrators say that Bloomington did not demonstrate a genuine need for development in the annexation territories within the "reasonably near future." Remonstrators say the correct interpretation of that phrase means four years based on the precedent in the 2019 Brownsburg case. Remonstrators point out in their brief that Bloomington's own mayor, Kerry Thomson, testified that the areas were not "needed." Private developers, not the city government, are responsible for housing development, the remonstrators say in their brief, and Bloomington did not present specific future development projects in the annexation areas.

Financial Impact

Bloomington claims that Nikirk found in his order that every annexation results in a significant financial impact on landowners, which is counter to the annexation statute and to established case law. The claim looks like it is based on this paragraph from Nikirk's order:

- Ms. Sharp testified that in her opinion anytime someone is annexed there is a significant financial impact [Testimony of Sharp]. The Court concludes that, in this case, the owners and residents of property in Areas 1A and 1B will experience a significant financial impact.

Bloomington says in its brief that the financial impact of the city's annexation is not "beyond the norm," especially given Bloomington's relatively low municipal tax rate.

On this point, the brief filed by remonstrators says that Nikirk's finding of a significant financial impact is supported by evidence that landowners in the annexation areas will pay over $22 million in additional property taxes in the four years following annexation. Remonstrators say Nikirk relied on the fact that that Bloomington's estimated property tax increases were based on outdated property assessment values, which have risen. The brief from remonstrators says there is no "beyond the norm" requirement explicitly stated in state annexation law.

Best interest of landowners

Bloomington says that the question of the "best interest of the owners of land" should be based on objective factors, like the overall fiscal health and socioeconomic well-being of the municipality and the region, not just the subjective opposition of landowners.

During the weeklong benchtrial, Bloomington used the better part of a day to introduce testimony related to "best interest" of landowners, from what could be considered its star expert witness, David Rusk, who is a Washington, D.C. consultant, and author of the popular book "Cities without Suburbs."

In its brief, Bloomington cites Rusk's testimony, that the annexation of Areas 1A and 1B is essential to the continued fiscal health of Bloomington and the region, which in turn is in the long-term, objective best interest of the landowners in the annexation areas.

Rusk said that the region's socioeconomic well-being depends on this annexation, making it objectively beneficial for the landowners, despite their potential opposition.

On this point, the remonstrators say that answering the "best interest" question should include the opinions of landowners in the annexation areas, and their satisfaction with current government services. Remonstrators say the evidence presented to the trial court showed that landowners are overwhelmingly satisfied with their existing services and would not receive much different services from Bloomington, despite a significant tax increase.

Wording of Nikirk's order

In many court proceedings, the judge will ask both sides to submit a proposed order, and then use parts of each order to craft their final order.

Bloomington's brief says that Nikirk used for his order nearly verbatim some of the proposed findings and conclusions from the remonstrators—in fact, for some crucial parts of it. Bloomington says Nikirk's verbatim use of the wording from remonstrators in those sections raises questions about whether the order reflects Nikirk's "considered judgment." Because of that, Bloomington's brief calls for extra scrutiny of Nikirk's ruling by the Court of Appeals.

On this point, the remonstrators say that Nikirk did not adopt verbatim the remonstrators' proposed findings, but used portions from both the parties to write his own order. In their brief, remonstrators note that Nikirk personally inspected the proposed annexation areas, at the request of both sides, and thus reached a conclusion that reflected his own considered judgement.

Comments ()