Bloomington city council districts don’t guarantee geographic diversity (Or: Steve Volan is the center of the political Bloomiverse)

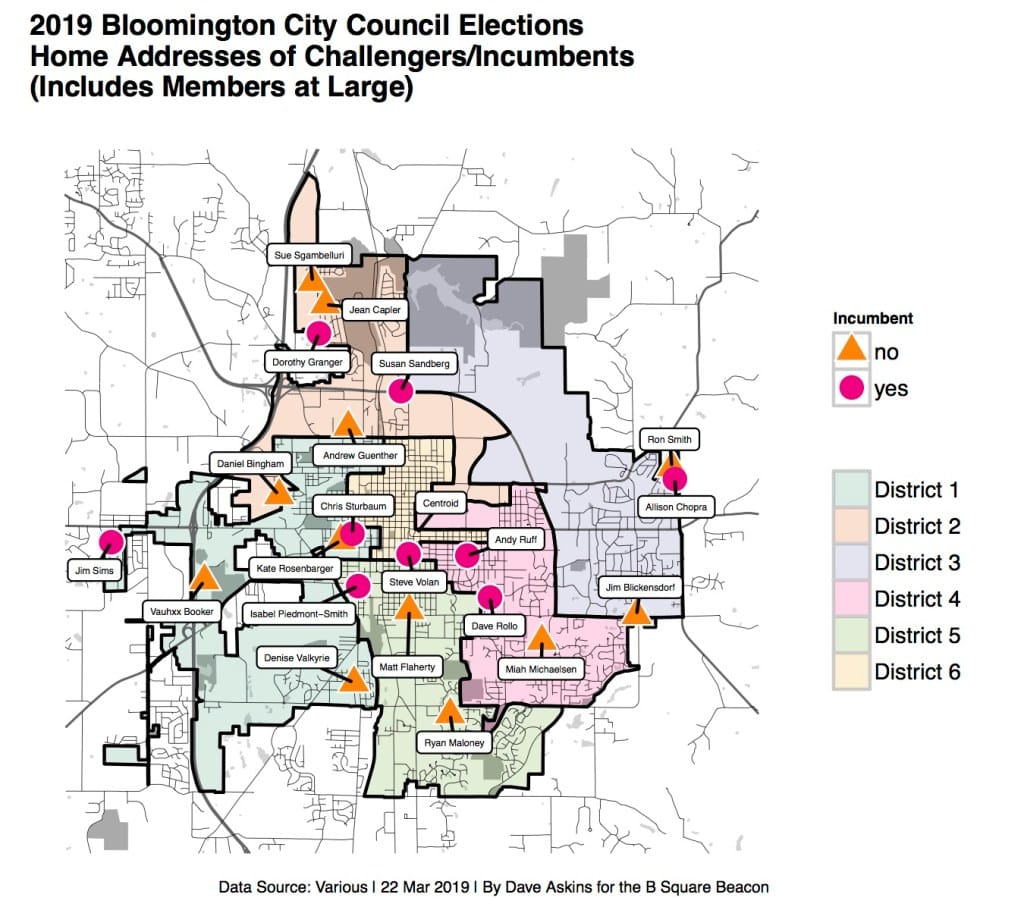

City Councilmember Steve Volan lives almost exactly in the middle of Bloomington.

The center of Bloomington’s area—the centroid calculated by a piece of geographic information software called QGIS—lies a few feet west of Indiana University’s Henderson Parking Garage on Atwater Avenue.

And of the nine people who represent Bloomington residents on the City Council, the one who lives closest to that exact geographic center of the city is Steve Volan. It’s about a quarter mile from the parking garage to his place.

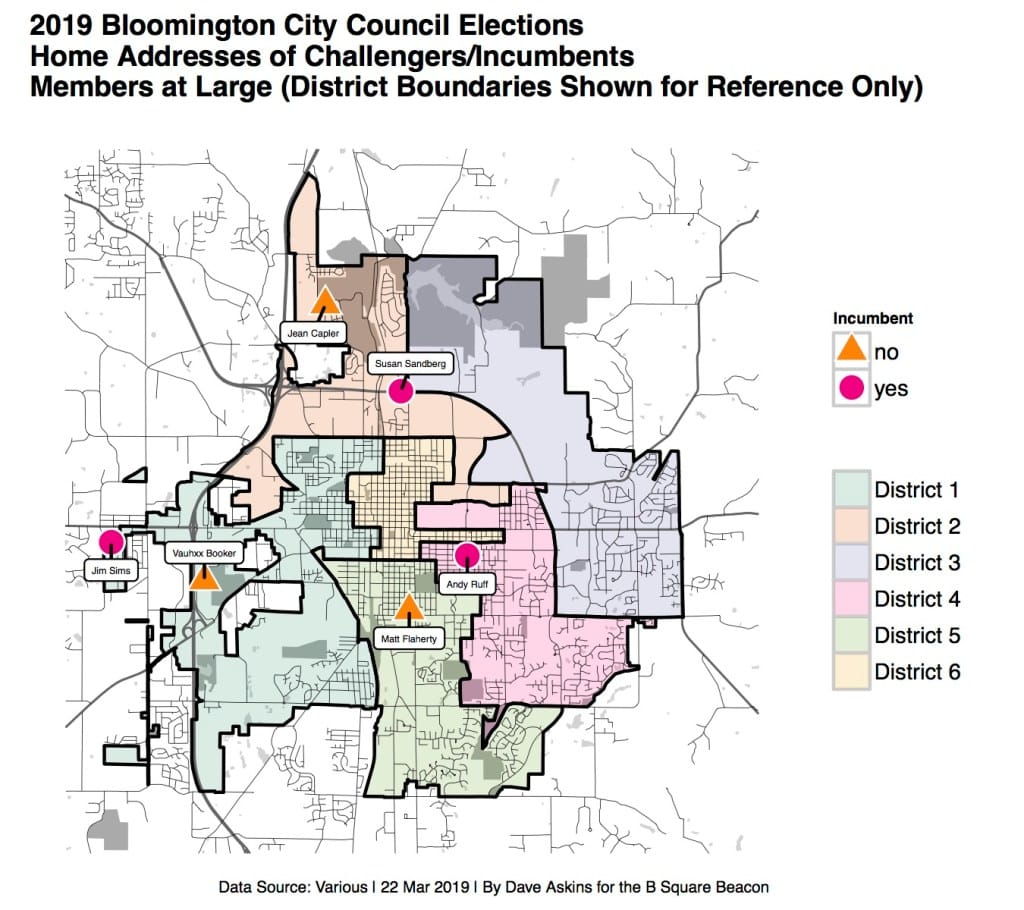

A few other councilmembers are clustered there with Volan in the middle of the city. If a circle with a 1-mile radius is drawn around Volan’s address, five out of the nine councilmembers, including Volan, live inside that circle.

That’s a point of contrast between incumbents and challengers in the upcoming May 7 primary election.

Only two of 12 challengers live inside that circle.

This year all city council seats are up for election to four-year terms, and eight of the nine councilmembers are seeking re-election. Not running is Allison Chopra, who represents District 3. And no one besides Volan is currently running for the District 6 seat.

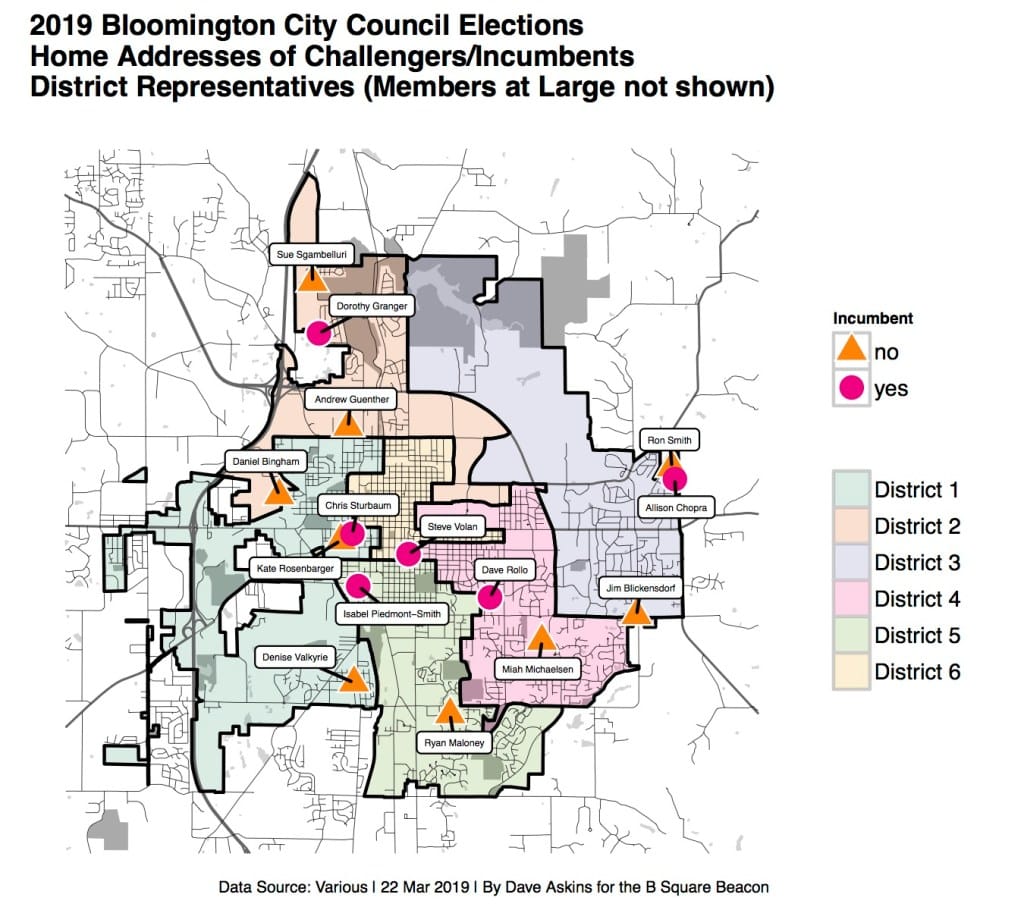

If the three at-large councilmembers are removed from the mix, the 1-mile circle still includes four of the six other councilmembers, who are each elected from a single district. But the circle includes just one of nine challengers for a district seat.

Certainly dividing a place like Bloomington into six city council districts, one representative per district, fosters a certain amount of geographic diversity for elected representation to the local legislature.

But the distribution of current councilmembers shows that the six districts, as they’re currently laid out, don’t guarantee a uniform geographic distribution of councilmembers across the city. A study of the population density of the city would probably show it isn’t uniformly dense. To the extent that the population might be clustered towards the middle of the city, it’s unlikely that a clever redistricting might prevent a similar clustering towards the middle for city council representatives.

Has the clustering of representation in the city’s geographic center caused the city council to pay inadequate attention to issues that matter to people who live in the city’s farther flung areas? To whatever extent that might be true, one possible remedy is reflected in the number of challengers this election cycle who live outside the city’s geographic core.

A different remedy, if a problem is perceived, could be pursued by those who are elected to the city council this year. They’ll be serving in 2022, the second year after the federal decennial census. That’s when the council districts for “second-class” cities in Indiana like Bloomington will be redrawn if necessary, according to state statute. (“Second-class” cities in Indiana are designated as those with a population of at least 35,000 and up to 600,000.)

The criteria that districts have to satisfy include: reasonable “compactness”; respect for precinct boundaries except in certain cases; and balanced population, among other things.

Here are some labeled versions of the maps showing the distribution of candidates and incumbents (click on any image to get a larger version presented as a slideshow):

Comments ()