Bloomington deer feeding ban starts Sept. 1

Starting on Sept. 1, Bloomington residents who feed deer could face a fine of $50.

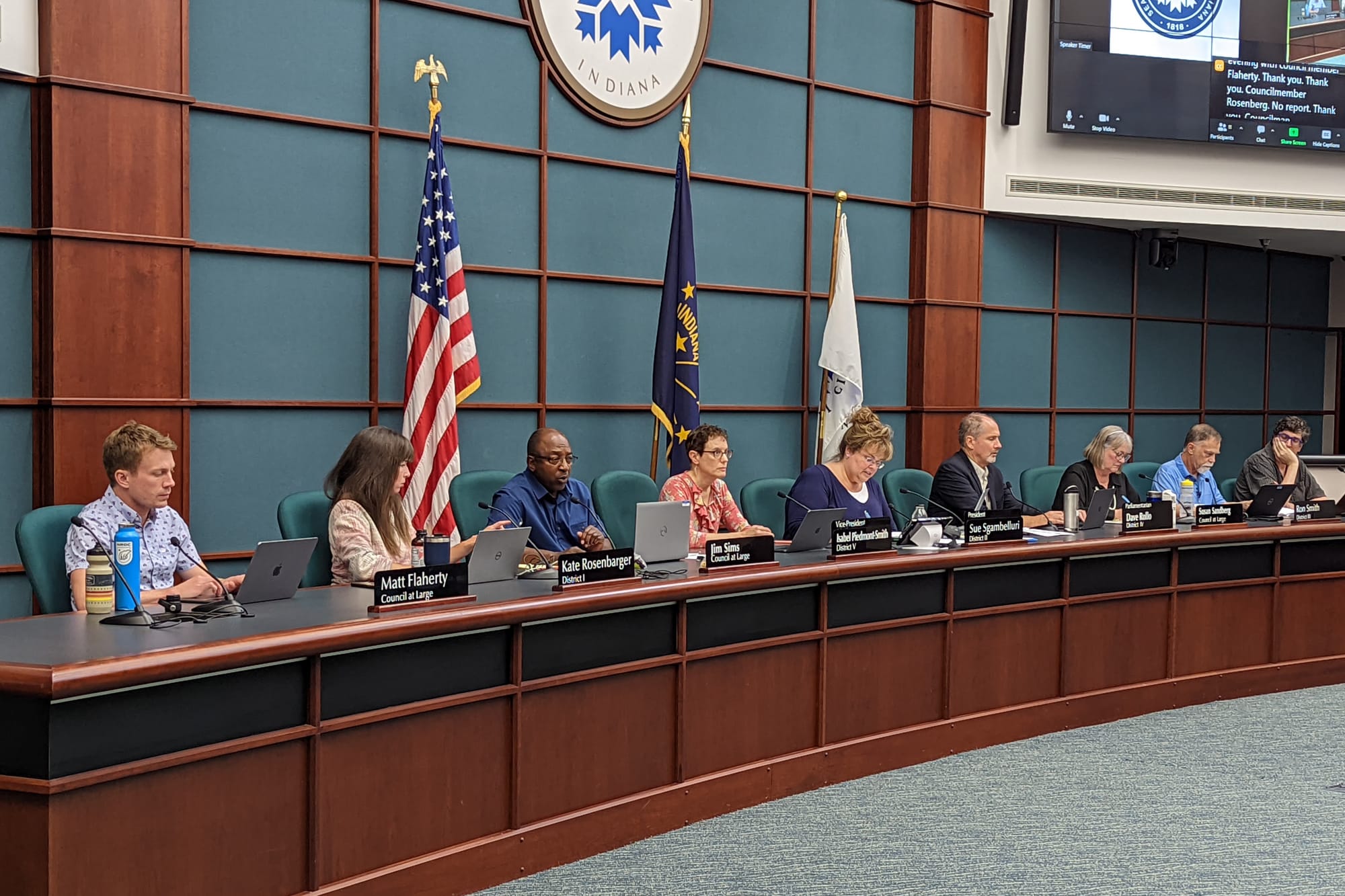

Under the ordinance that was approved by Bloomington’s city council on Wednesday night, if someone is found feeding deer a second time, within a year of the first offense, the fine doubles to $100.

And every subsequent offense within 12 months racks up a fine that doubles each time.

On Wednesday night, Bloomington animal shelter director Virgil Sauder said that enforcement of the ordinance would be based on reports his office receives about deer being fed.

The ordinance enacted by the city council on Wednesday includes some other amendments to the city code on animals, like revisions to the definition of a dangerous animal.

Under the ordinance, animal adoption fees were also increased. Currently, dogs and cats under five years are $75, and older than five years are $55. Under the new fee schedule, there are no age brackets—dogs and cats have an adoption fee of up to $120.

Sauder laid out for the council the reason for the ban. When deer are fed by people, they tend to congregate in larger numbers, where that feeding takes place. The larger groups of deer mean an increased risk of disease spread among deer. The food that people set out is also not a part of a deer’s natural diet, which can cause health concerns for the deer, Sauder said.

Sauder said the deer feeding ban relies on the work of a 2012 task force.

The ordinance was not controversial for councilmembers. It was approved on a 9–0 vote.

The two key notions associated with a ban on feeding deer are what counts as an act of feeding deer and what counts as food.

The ordinance defines food with a list of items:

(c) For the purpose of this section, the following shall constitute food: corn, fruit, oats, hay, nuts, wheat, alfalfa, salt blocks, grain, vegetables, and commercially sold wildlife feed and livestock feed.

To decide if an act of feeding is taking place, the code asks how high off the ground food is placed. Under the definition, putting food any place that is under five feet off the ground counts as feeding deer:

(b) A person shall be presumed to have intentionally fed deer, or made food available for consumption by deer, if the person places food, or causes food to be placed, on the ground outdoors or on any outdoor platform that stands fewer than five feet above the ground.

Councilmember Rosenbarger asked how the definition of feeding applies to scattering birdseed on the ground. Sauder said that bird feed on the ground is excluded from what’s considered food for deer—so if someone scatters bird feed on the ground, that would not be considered feeding the deer. Birdseed is among several items listed out in the ordinance that are not considered “food” for deer.

Other such items include: planted material growing in gardens or standing crops; naturally growing matter, including but not limited to fruit and vegetables; fruit or nuts that have fallen on the ground from trees; stored crops, provided the stored crop is not intentionally made available to deer; feed for livestock and/or the practice of raising crops and crop aftermath, including hay, alfalfa and grains, which is produced, harvested, stored or fed to domestic livestock in accordance with normal agricultural practices; and a lawn or garden.

Deer-related topics of interest for councilmembers on Wednesday mirrored those discussed at a council meeting in May, when Sauder gave a report on the topic of the planned ordinance banning the feeding of deer.

Councilmember Dave Rollo said he wants the city to take a census of deer inside the city so that the effect of deer abundance can be assessed. The city has the necessary drone technology to do such a count, Rollo said.

Rollo also pointed out there’s a public health impact because of deer ticks, which can spread disease to people.

On Wednesday, Sauder told Rollo that the studies he has read indicate that reducing deer population does not necessarily coincide with reducing tick population. Rollo responded by telling Sauder that he would be sending him a journal article that concludes there’s a relationship between deer population and tick populations.

Sauder was not keen to immediately count the deer population inside the city, unless there’s a policy decision made to lower the number of deer. If lowering the deer population is the city council’s policy direction, then counting deer would make sense, Sauder said.

Councilmember Jim Sims called uncontrolled deer a public health hazard. He told Sauder he did not think Sauder needed a mandate from the city council to say that the goal is to reduce the deer population. Sims said it’s something that Bloomington should work towards.

Comments ()