Bloomington electeds talk budget outcomes as cheese gets sliced thinner

On Wednesday night, Bloomington mayor Kerry Thomson and some councilmembers sat down in council chambers around tables arranged in a rectangle, to talk about the 2026 budget.

Joining them were deputy mayor Gretchen Knapp, city controller Jessica McClellan, Eric Reedy, the city's financial consultant, and city clerk Nicole Bolden.

The budget process for the city council will include four days worth of departmental budget hearings, which start on Aug. 18 and are spread over two weeks.

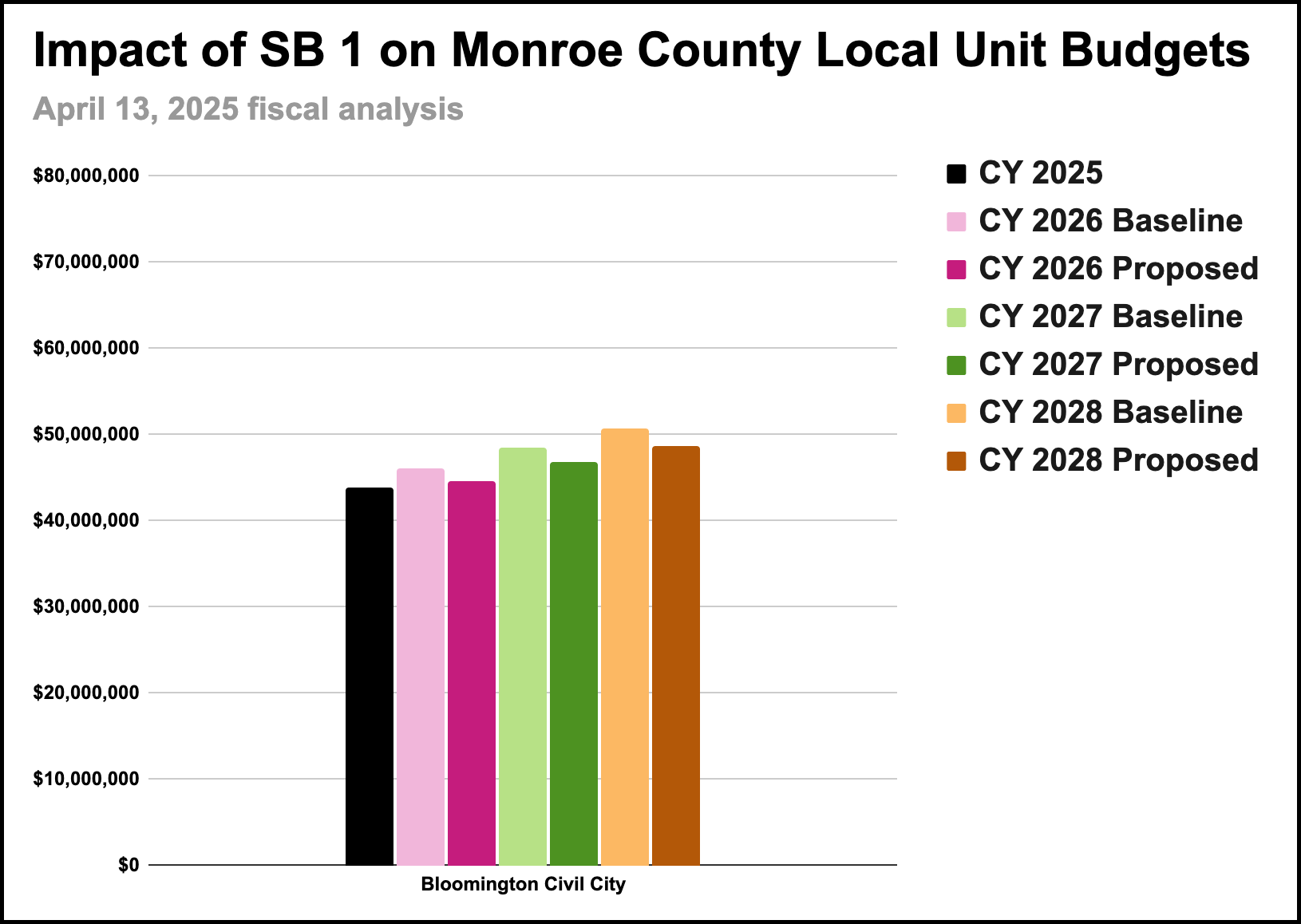

Some key takeaways from Wednesday's conversation included the idea that the impact of SB 1—the recently enacted revision to property tax and local income tax (LIT) law—will mean much less revenue for the city government, but the impact will be a little less severe for Monroe County government.

Another takeaway is that the city government will have less control over its local income tax revenues than it previously had. SB 1 sets up a scenario starting in 2028, where the city of Bloomington will probably have to rely on the Monroe County council to enact the full amount (0.4%) of the new fire/EMS LIT that the county government controls.

If the fire/EMS LIT is enacted at the full 0.4% rate, the city's share of it would almost, but not quite, make up for the total shortfall the city will see because of the reduction in revenues from LIT and property taxes—compared to what it would have received before SB 1. That's according to Reedy's initial analysis.

Basic approach: Maintain existing services

The prospect of having less revenue next year, and in the following years, led Bloomington mayor Kerry Thomson to say on Wednesday, "I think going into this budget season, especially given the various uncertainties, the tone that I'm taking really is that we want to do really well at maintaining what we already have—fulfilling the commitments that we've already made, and fulfilling basic city services."

Thomson added, "This is really not a year that I'm interested in large new projects, big new initiatives."

For both the city and the county governments, it's true that the shortfall in property taxes could be made up, at least in part, with increases to LIT.

About the strategy of imposing LIT to make up for property tax revenue loss, Thomson said, "I take very seriously the LIT and the amount that we are taxing our residents, especially because, in our community, we have a very clear bimodal distribution of wealth." Thomson added, "There are people who really are already struggling with our current taxation. They're struggling day to day."

That general approach of maintaining basic city services seemed to resonate with councilmembers. Sydney Zulich put it like this: "It is really great to know that we're all on the same page about just maintenance, and making sure that at the end of the day the city functions the way that it's supposed to function, and that we have roofs over as many residents…food on as many of their tables as possible."

Outcome-based budgeting

Between now and late July, the administration will be working to flesh out the consensus "outcome areas" that a budget task force hammered out at its Monday meeting. The task force includes councilmembers and city staff. On Monday it was councilmember Isak Asare and deputy mayor Gretchen Knapp who engaged in a long back-and-forth to arrive at a list of six "outcome areas" that will form a structure for framing the budget "offers" that will be made by department heads.

In the outcome-based budgeting approach that the council and mayor are trying to move towards adopting this year, budget proposals are described as "offers." From a white paper that Asare wrote, here's how the concept of a budget offer is described: "[D]epartments submit 'offers' instead of incremental budget requests. Each offer should clearly state what is being proposed, the associated cost, the outcomes it aims to impact, and how success will be measured." The white paper further describes what the role of the council is: "Offers are reviewed and 'purchased' based on how well they support city outcomes."

Here are the six outcome areas that were accepted by the councilmembers present at Wednesday's meeting:

Outcome areas

- Affordable housing and homelessness

- Public safety

- Community health and vitality

- Economic development

- Transportation and mobility

- High-performing government

The six areas reflect a reduction in the number of outcome areas from the city council's eight that were included in a letter to the mayor that was approved by the council at its May 7 meeting. Not attending the council's Wednesday meeting were Matt Flaherty, Kate Rosenbarger, and Hopi Stosberg.

Based on Wednesday's meeting, it doesn't sound like there will be further public conversations between the administration and councilmembers until after the council's annual "summer recess" which this year goes from June 5 (the day after its June 4 regular meeting) until July 16.

New Local Income Tax Structure: Less money for Bloomington

In the framework of SB 1, the local income tax (LIT) percentages that can be imposed by different jurisdictions look like this starting in 2028.

New for this approach is the idea that cities will impose an income tax on just its residents. The current approach to any category of LIT is to collect all the revenue into one pot, then distribute it based on property tax footprint or population—which is only a rough approximation of the amount that the residents of each jurisdiction actually pay in local income tax.

The calculations that Eric Reedy (Reedy Financial Group) did for the 1.2% of LIT that Bloomington has its own authority to impose on city residents look like this for 2028:

- Bloomington 2020 US Census average household income = $60,888

- Bloomington 2020 US Census occupied housing units = 33,204

- Bloomington calculation for 2020 = $2,021,725,152 total adjusted gross income

- Monroe County calculation for 2020 = $3,461,871,747 total AGI

- Bloomington's 2020 proportion of Monroe County AGI = 58.4%

- Monroe County 2025 AGI = $4,408,022,336

- Bloomington 2025 AGI = $2,574,274,924

[58.4% * $4,408,022,336 ] - Bloomington residents total @ 1.2% for 2025 = $30,891,299

[1.2% * $2,574,274,924] - Bloomington residents total @ 1.2% for 2028 = $33,755,757

[$30,891,299 @ 3% increase for 3 years]

In the current system, Bloomington gets a total (including public safety local income tax) of $36.92 million in LIT this year. That total comes from this arithmetic: $15,383,282 (certified shares) + $4,308,965 (public safety) + $17,234,163 (economic development).

Three years of growth at 3% on $36.92 million would amount to $40,350,485, which is around $7 million more than Bloomington is projected to receive in LIT revenue under the new scheme—as far as the LIT goes that is under the city's own control.

Less property tax revenue

Based on the fiscal analysis that was released with the final version of SB 1, the total amount of property taxes received by all governmental units in Monroe County will be about $9 million less in 2026, due to SB 1, compared to the level of tax revenue they would otherwise receive.

A more detailed analysis of an earlier version with numbers broken down by governmental unit, showed the city of Bloomington down about $1.4 million (3.2%) in 2026, from a baseline of $46,111,291.

SB 1 includes a maximum levy growth quotient (MLGQ) of 4.0%, which is the same as it was last year. Still, other features of SB 1 converge to an outcome of less tax revenue for governmental units. Those other features include circuit breaker tax credits.

Generally, once the amount of the levy is decided—which is a maximum of 4.0% more than last year—the property tax rate is set at a level that would generate the levy amount, if the rate is applied to the assessed value of all the property. But the state of Indiana caps property taxes at 1% of assessed value for homesteads, 2% for rental and agricultural property, and 3% for commercial and industrial.

After applying the rate that was set, the caps mean that if the resulting tax bill for a property winds up higher than the cap, the tax bill for that property is lowered to the cap amount. For example, if the taxable value of a house is $100,000, then the homeowner's property tax is capped at 1% of that—$1,000. If the local tax rate would otherwise generate a $1,200 bill, the extra $200 becomes a circuit breaker credit, which the city cannot collect. That's how property taxes in Indiana have worked for several years.

What SB 1 does is increase deductions for many property types. These changes reduce the taxable value of properties, causing more of them to reach their tax caps at lower dollar amounts. And that means less revenue to local governmental units. Reedy said on Wednesday that a parcel-by-parcel analysis would be needed to determine the precise impact of SB 1 on Bloomington property tax revenue.

Making up for reduced revenue

To make up for the lost revenue from property taxes and from LIT that is under Bloomington's control, the city will be likely be looking to the Monroe County council to enact at least some of the 0.4% of local income tax that is under the county government's control, to support fire/EMS services.

If 0.4% is applied to the $4,408,022,336 adjusted gross income for Monroe County in 2025, that would yield $17,632,089 for fire/EMS for the whole county. Applying three years of 3% growth to that number would give $19,267,060. Under SB 1, the distribution to fire protection agencies is determined by a formula based on population and square miles. According to Reedy's calculations, about 53.8% of the total fire/EMS LIT would go to Bloomington's fire department.

Applying 53.8% to $19,267,060 would give Bloomington $10.36 million for fire protection in 2028. Bloomington would easily be able to use all of that revenue just on fire protection. Bloomington's budget this year for the fire department is around $20.5 million.

But it's not a given that the Monroe County council would impose the full 0.4% of LIT that's allowed for fire protection. The initial numbers that Monroe Fire Protection District has calculated put the MFPD's needs at the revenue level that would be generated by about 0.25% LIT.

Left: Chart by The B Square with data from the state of Indiana. Right: The image was created by DALL·E, an AI image generator developed by OpenAI.

Comments ()