Bloomington extends tax break for troubled low-income housing complex, citing ’factors beyond the control of the property owner’

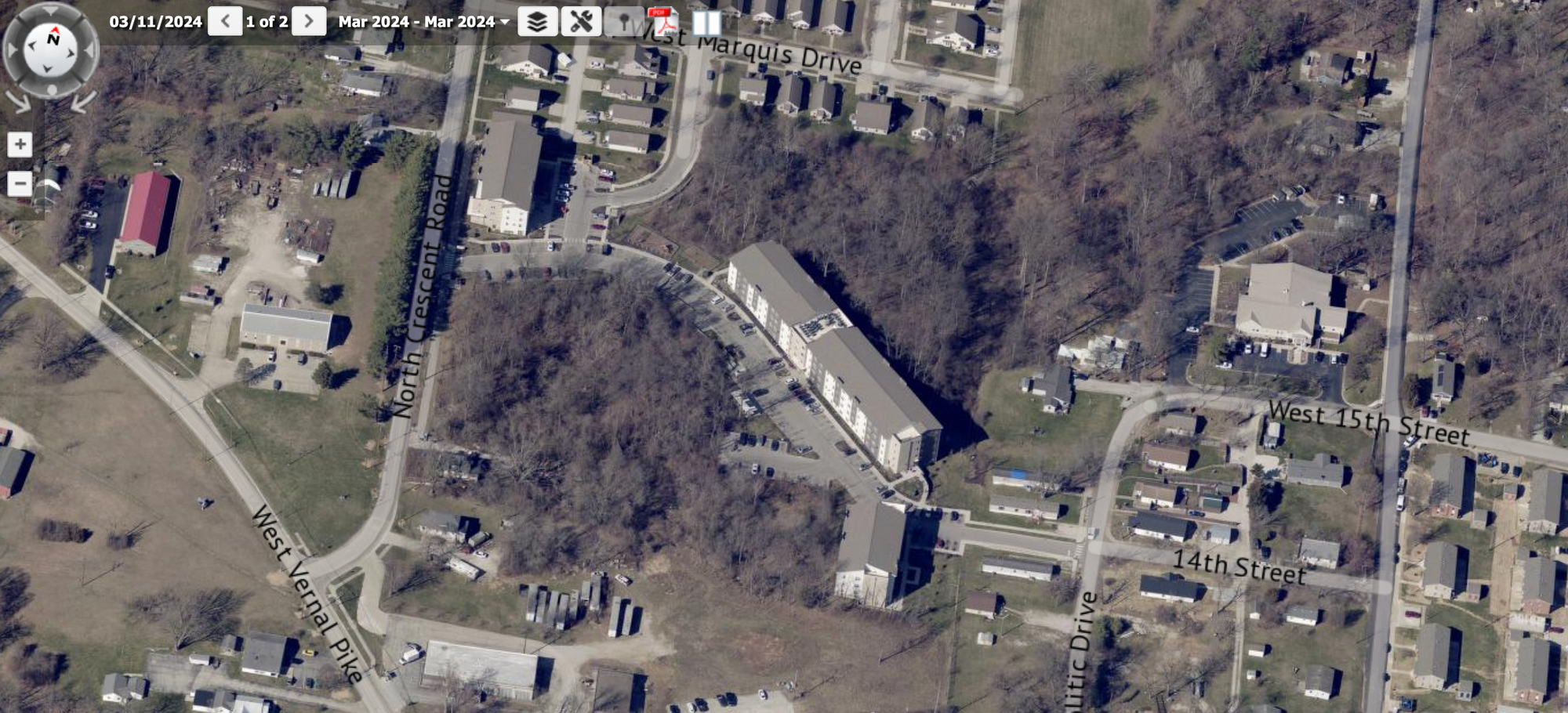

Union at Crescent, a 5-story affordable housing development with 146 units in the northwest part of Bloomington, will continue to receive a tax abatement. The city council concluded that “any failure to substantially comply was caused by factors beyond the control of the property owner.”

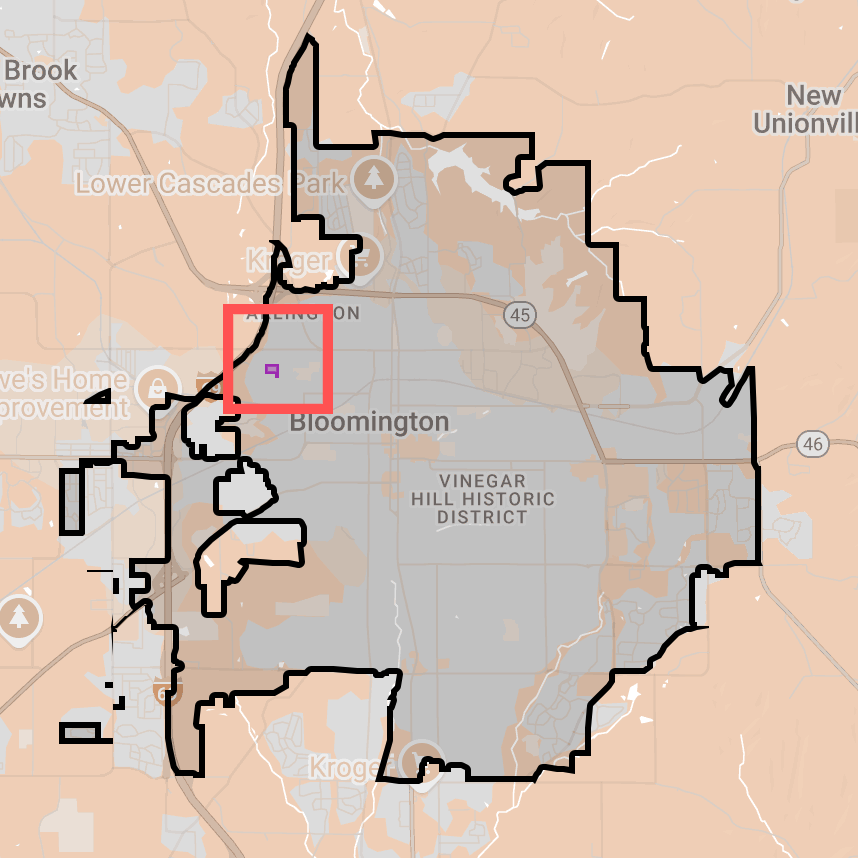

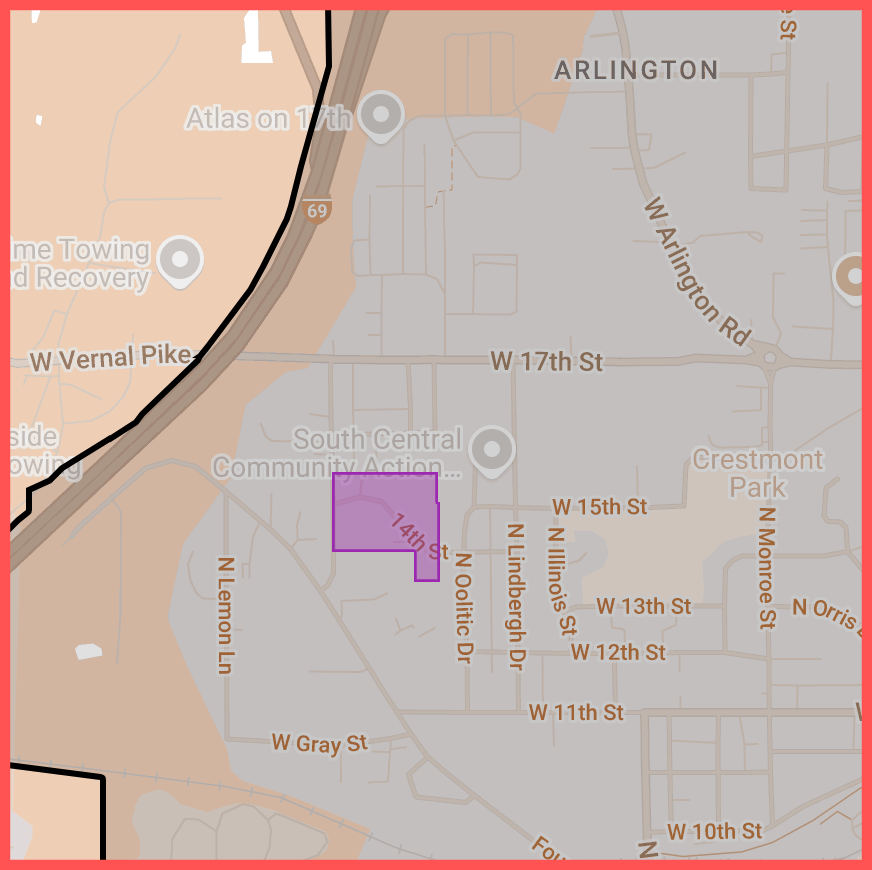

Maps by The B Square with data from city and county government sources.

Union at Crescent, a 5-story affordable housing development with 146 units in the northwest part of Bloomington, will receive an abatement on the taxes it pays in 2026, in the same way that it has the last four years.

The low-income housing development has struggled with tenant-caused damage, failed rental inspections, and substantial rates of non-payment of rent, contributing to an overall perception of an unsafe environment. That situation has driven out reliable tenants, leaving the property under-occupied—below the thresholds set by the terms of its tax abatement, approved by the city council in 2017.

But after more than an hour and a half of deliberations on Wednesday night, Bloomington’s city council found that “the property owner has made reasonable efforts to substantially comply with the Statement of Benefits, and that any failure to substantially comply was caused by factors beyond the control of the property owner. ” That finding kept the tax abatement in place.

The abatement has reduced the amount of taxes paid by Union at Crescent in 2025 by $114,720 and in 2024 by $112,261—based on assessed values in 2024 and 2023 respectively. In 2026, the amount of taxes to be paid based on the 2025 assessed value would be $161,947.

At issue was whether Union at Crescent, which was represented at Wednesday’s hearing by The Annex Group, had substantially complied with its commitment to allocate at least 70% of its units to households with incomes at or below 60% of the Area Median Income (AMI). That translates to 102 units at 60% AMI or lower.

For a two-person household, the 2025 AMI for the Bloomington area is $69,400, and the HUD income limit for 60% AMI in the Bloomington area for a two-person household is $52,080.

Based on information presented to the council on Wednesday, in May 2025, Union at Crescent had 43 occupied units with an average AMI of 19%, which is 59 fewer units than were supposed to be made available at the 60% AMI level.

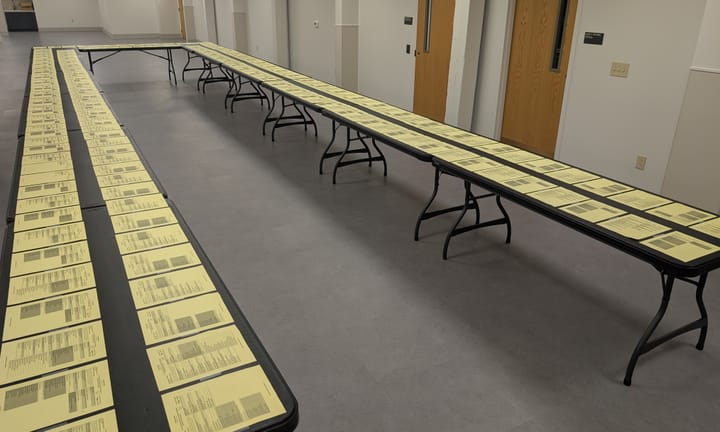

At its meeting in mid-July, the council had voted preliminarily to find that the development was out of compliance and that the noncompliance wasn’t due to factors beyond the control of the developer. That set the stage for Wednesday’s hearing.

Based on information presented to the city council on Wednesday, in September 2023, there were 119 units occupied at the 60% AMI level, which put the development in compliance.

But less than a year ago in September 2024, there were just 72 units occupied at Union at Crescent, with an average unit income of $14,409.96, which paid an average of $554.73 in rent plus utilities ($446.20 rent and $108.53 utilities).

Those figures changed in May 2025 to just 43 units occupied, with a lower average income of $13,039.20 and a significantly higher combined housing cost of $987.56 ($881.30 rent and $130.98 utilities).

That means over an eight-month span, the occupancy of affordable units dropped by 40%, while the average cost to tenants for rent plus utilities jumped by nearly 80%, even as average incomes declined. At Wednesday’s hearing, Sam Hurley was asked by councilmembers about the increase in rental cost, but an explanation was not readily available, as Hurley was unsure about the accuracy of the data.

Advocating for the continuation of the Union at Crescent tax abatement, Hurley made the technical legal point that the developer’s memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the city does not talk about “occupancy” of units but rather “allocation” of the units. From that perspective, the development was in compliance, because the units were still allocated to tenants with incomes at the 60% AMI level, even if they were vacant.

That argument wasn’t persuasive for the city council, or for city attorney Audrey Brittingham, who said about the “allocation” versus “occupancy” issue: “The MOU does refer to … these units have to be allocated.” She continued, “We’d argue that a 10-year tax abatement for a company to set units aside being designated as affordable … doesn’t justify 10 years worth of tax abatements from the council.” Brittingham added, “We’re not going to hold them strictly to that number. But this is a pretty large number of units that are not filled. So that’s the city’s position on the ‘allocation’ versus ‘occupancy’ issue.”

What proved to be persuasive to the city council was the idea that it is inherently difficult to serve the low-income tenant population that the development is trying to benefit.

Anna Killion-Hanson, director of the city’s Housing and Neighborhood Development (HAND) Department, described the situation like this “Units were being extensively damaged and abandoned by residents—feces, urination, needles were found throughout the project. Lights were damaged, exterior doors were damaged. Elevator service companies refused to service due to the urination, needles and feces.”

According to Killion-Hanson, violations were found in the latest round of rental inspections and the property has a deadline of Sept. 5 for compliance.

In response to a request from the B Square, Bloomington police provided data on calls for service from first responders to the Union at Crescent property for about the last year and a half.

Calls to Union at Crescent (Jan 1, 2024 to May 13, 2025)

Law enforcement: 810

Fire department: 86

Emergency medical services: 169

That works out to an average of more than two calls a day to the property.

At Wednesday’s hearing, speaking for The Annex Group, which took over full property management for Union at Crescent in March 2025, Sam Hurley acknowledged the problems and outlined some steps taken: hiring 24/7 security; investing over $500,000 in improvements; and setting a target of November 2025 to restore all affordable units for occupancy.

Hurley told the city council, “We are in a full turnaround mode … We are investing a significant amount of capital to get the security into a more robust state, adding cameras, adding door security, adding lighting, getting the property cleaned up.”

Killion-Hanson told the council that in March 2024 Union at Crescent had made a $3 million request from the city of Bloomington to implement security measures. That’s a request that the city was unable to meet, she said.

In her memo to the city council, director of economic and sustainable development Jane Kupersmith recommended a finding of noncompliance. But the city’s position came with some nuance.

The Union at Crescent project predates Killion-Hanson’s tenure as HAND director. She pointed to the fact that the project had previously received $300,000 in federal HOME funds and $500,000 from the city’s housing development fund. Based on the information available in the city’s online financial records, those city funds were provided in a series of 40 payments from March 2019 through February 2021. She described the city’s previous investment and the current situation as putting the city between “a rock and a hard place.”

Killion-Hanson told the council, “Ultimately, I believe that taking away their abatement is not going to help the situation. I think it just exacerbates the problem,which is that initially, the pro forma was not looked at correctly.” The pro forma for a project includes financial projections and outlines the expected costs, revenues, and performance of the project over time. The pro forma for Union at Crescent did not include an adequate allowance for security, Killion-Hanson indicated.

Killion-Hanson added, “I am doing [more careful review] as we’re evaluating future projects, but this is obviously something that was not looked at closely initially.”

On the council’s side, it was Matt Flaherty who most clearly echoed the sentiments of the city attorney about the inadequacy of an “allocation” of units to tenants at the 60% AMI level—when the expectation connected to a tax abatement would be occupancy. Flaherty put it like this: “I think the concept of occupancy is wrapped up in [allocation]. And I think it’s kind of an absurd conclusion to say that all they have to do is allocate the units, and 0% occupancy would be fine.”

Councilmember Andy Ruff, pointed to the broader context of other tax abatements involving industrial applicants, and the idea that the council was often willing to cite factors beyond the control of a company. Ruff said, “With tax abatements that aren’t related to residential, we constantly find things like free market forces: Oh, they couldn’t have foreseen that, so it’s beyond their control.” Ruff indicated he would support extending Union at Crescent’s tax abatement for another year.

The council’s discussion about postponing the tax abatement decision included the possibility of waiting until October or even the end of the year, to see if the steps that the Annex Group was taking would improve occupancy in the short term. A motion to put off a decision until the next council meeting failed, with support only from Sydney Zulich, Hopi Stosberg, and Isabel Piedmont-Smith.

The vote on the question of compliance came shortly after the failed vote to postpone, passing 8–0. (Dave Rollo was absent.)

Comments ()