Bloomington MLK celebration highlights Coretta Scott’s activism and unfinished work

At Bloomington’s MLK celebration Jan. 19, UC Davis historian Traci Parker urged the audience to see Coretta Scott King as a central architect of the movement, not simply MLK’s widow. The program also honored Ruth Aydt with the MLK Legacy Award.

Traci Parker, keynote speaker at Bloomington’s annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Birthday Celebration. (Dave Askins, Jan. 19, 2026)

At Bloomington’s annual MLK celebration, held on Monday (Jan. 19), keynote speaker Traci Parker described Coretta Scott King as a central architect of the Black freedom struggle, not merely the widow of Martin Luther King Jr.

Parker is associate professor of history at the University of California, Davis.

The program for the city’s annual celebration, held at the Buskirk-Chumley Theater, also included presentation of the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Legacy Award to Ruth Aydt, honoring her years of grassroots work to document and confront racial inequity in Monroe County. Some of that work included helping to research racial disparity at the Monroe County jail.

In her keynote, Parker told the audience that the federal Martin Luther King Jr. holiday itself stands as a monument to Coretta’s political labor—her years of lobbying, coalition-building, and public advocacy after her husband’s assassination. She stressed that “Mrs. King” was already the seasoned activist Coretta Scott, long before she met Martin.

Parker recounted Coretta’s childhood in Jim Crow Alabama and her formative years at Antioch College. At Antioch, Parker said, “[Corretta] became politically active while confronting the limits of Northern liberalism, and came to understand that peace was inseparable from justice—without justice, there was no peace.”

A radicalizing event at Antioch came when Corretta was barred from student-teaching in local public schools because she was Black. That episode, Parker said, pushed Coretta toward a lifelong commitment to racial justice and peace, before her relationship with King.

Describing their marriage, Parker noted that Coretta insisted on a partnership of equals: At the wedding ceremony, she wore a blue gown symbolizing freedom, kept her own name, removed “obey” from the vows, and expected to maintain a public career. Behind the scenes, she helped shape King’s speeches while pressing him to recognize that she, too, had a “calling” that extended beyond domestic life.

By the early 1960s, Parker said, Coretta had emerged as a national and international voice, speaking against nuclear weapons and the Vietnam War, working with Women Strike for Peace and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and using “freedom concerts” to keep the Southern Christian Leadership Conference afloat and to link culture with protest. Two years before her husband’s famous sermon against the Vietnam War at Riverside Church, Corretta addressed an anti-war rally at New York City’s Madison Square Garden, the only woman to address the crowd, Parker said.

Four days after King’s assassination, Parker said she marched with nearly 50,000 people to support the Memphis sanitation workers strike for better wages and working conditions. She was crucial to advancing the Poor People’s Campaign, even as her husband’s former male collaborators sought to silence and marginalize her, Parker said.

Coretta launched the southern caravan of the Poor People’s Campaign from the same balcony where her husband was assassinated. Referring to King’s famous “I have a Dream” speech, she declared her own dream, Parker said, that America would be a place “Where not some, but all God’s children have food. Where not some, but all God’s children have decent housing. Where not some, but all God’s children have a guaranteed annual income, in keeping with the principles of liberty and grace.”

Parker highlighted Coretta’s blunt description of structural violence as having an effect that is as real as a physical attack. Quoting Coretta, Parker said, “Neglecting school children is violence. Punishing a mother and her family is violence. Ignoring medical needs is violence. Contempt for poverty is violence. Even the lack of willpower to help humanity is a sick and sinister form of violence.”

In the decades that followed, Parker noted, Coretta founded the King Center, led the fight for the federal holiday, opposed apartheid and unjust international debt, championed labor rights, backed the Equal Rights Amendment, and became an early, forceful advocate for LGBTQ rights.

Parker’s remarks underscored the idea that Coretta Scott King was a revolutionary in her own right. To properly honor “the Kings,” she said, requires recognizing Coretta’s independent, intersectional agenda—linking racial justice, peace, gender equality, and economic security—a project Parker said remains unfinished.

Parker called on the audience to continue the work: “Let us carry forward their unfinished work in moments of darkness. May we choose courage in the face of injustice. May we refuse indifference and in our lives, may we become what they were—freedom fighters committed to justice for all.”

2026 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Legacy Award winner Ruth Aydt: “So many in our community give tirelessly to advance racial equity and justice and to foster belonging. Aydt described her own work as a continuing journey of learning and unlearning: “The more I learn, the more I realize the scope of what I don’t know and have been conditioned not to see in the past and in the present. Aydt asked residents to do more than offer thanks to Black leaders and organizations: “Please do more than thank them. Listen to what they are saying. Consider what gifts and talents you might contribute.” (Dave Askins, Jan. 19, 2026)

Left: Bloomington’s city clerk, Nicole Bolden, with her mother, Monroe County circuit court judge Valeri Haughton. Right: Bloomington city council president Isak Asare and Monroe County council president Jennifer Crossley. (Dave Askins, Jan. 19, 2026)

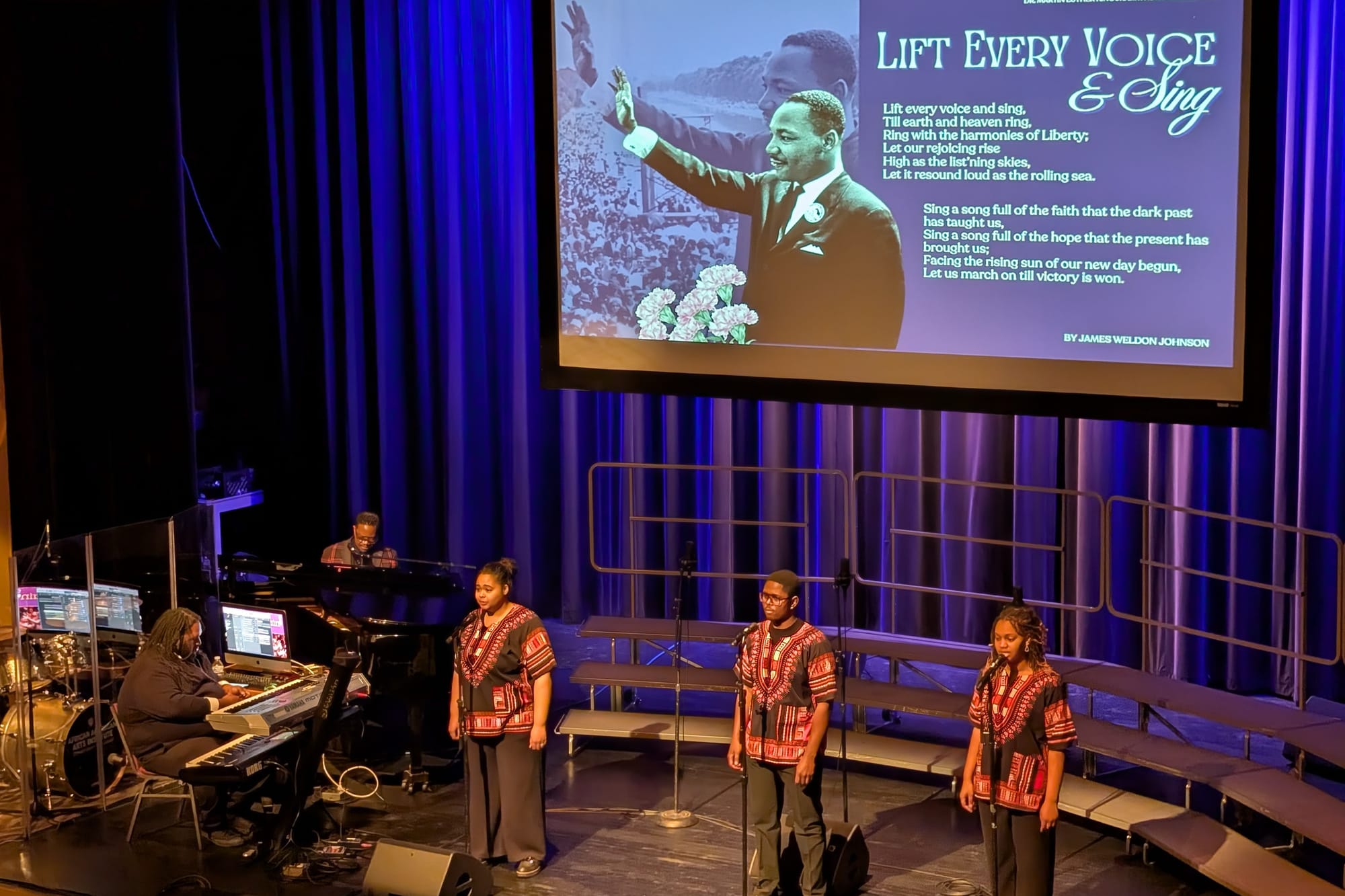

Members of the Indiana University African American Choral Ensemble perform under the direction of Raymond Wise. (Dave Askins, Jan. 19, 2026)

Comments ()