Bloomington OKs single-house historic district or: A lesson in cursive writing—how to form the letter ‘p’

At its final meeting of the year on Wednesday, Bloomington’s council approved the establishment of a single-house historic district.

It’s the Reverend James Faris House at 2001 East Hillside Drive, which is in the southeast part of town.

The vote on Wednesday by the city council was uncontroversial. In mid-October, Bloomington’s historic preservation commission had given a recommendation for the historic designation of the house. The property is rated as “Notable” in the State Historic Architectural and Archeological Research Database (SHAARD).

The house was determined to satisfy both categories of criteria for designation: historic and architectural.

On the architectural side, the house was determined to show an architectural style, detail, or other element in danger of being lost and to exemplifies the built environment in an era of history.

According to material provided in the meeting information packet by Gloria Colom Braña, Bloomington’s historic preservation program manager, the house is a “remarkably intact example of the I-House form.” The style was prominent in Indiana from 1820 to 1890, according to the staff memo. The house is built from handmade brick which means that it was dug and fired on site, according to the memo.

On the historic side, the Reverend James Faris, who built the house, became the first pastor of the Bloomington Reformed Presbyterian church in 1827. Faris was born in South Carolina in 1791, and moved to Bloomington in 1826, according to the staff memo.

He was a purported conductor on the Underground Railroad, according to the resolution establishing the district.

The house was renovated by its current owners, William Bianco and Regina A. Smyth, who purchased it in 2006. They were on hand at Wednesday’s meeting to field some questions from councilmembers about the energy efficiency of the old windows.

Also on hand Wednesday was Scott Faris, great, great, great grandson of James Faris. Scott Faris clarified the provenance of a typed out narrative he had sent along, and which was included in an addendum to the meeting information packet.

At the bottom of the typed out narrative is recorded “D.C. Faris”—which Scott Faris told the city council stood for David Faris, who was one of James Faris’s four sons. All four grew up to be clergymen, according to Scott Faris.

David Faris’s early interest in his father’s vocation is included in the typewritten narrative about his recollections of the house (emphasis added):

The stairway was along the west half of the south wall of the sitting room. At the corner it turned with three cornered steps, and the landing on the upper floor was at right angles to the first steps, It was boarded up all but two or three steps at the bottom, which were in the sitting room, a door above them closing the stairway under it, I think, was a little closet. The highest of the steps in the sitting room was my first pulpit. I remember the most eloquent part of one of my sermons preached there which was, ”The iron rod of the meeting house” and “the iron fetters of jail.” For these two things, in my childish view, presented the most sublime thoughts.

Also a part of David Faris’s recollections were his lessons in cursive writing:

Each pot hook had a hook at each end, one by which it hung on the crane, and the other by which the kettle hung up. It was from these hooks that certain parts of letters we were learning to write we called pot hooks, viz: the low part of the letter h, and the last leg of the letters m and n and p; and first stroke of u, v, w, and y, because of their resemblance to the hooks which hung on the crane in the kitchen fireplace.

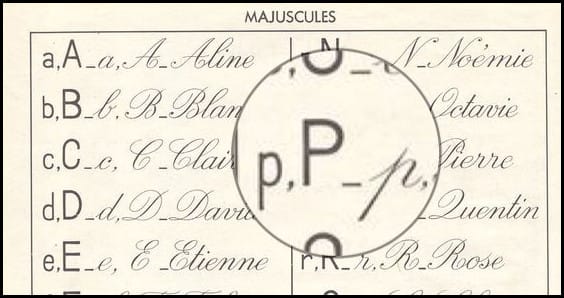

For B Square readers who learned cursive writing growing up in southern Indiana—it is still taught in the Monroe County Community School Corporation—the similarity described by David Faris could seem dubious: “the last leg of the letters m and n and p…”

But apparently the French style of writing, at least at that time, prescribed that for a lower-case ‘p’ the descending portion of the final stroke did not complete the bowl at the bottom.

Comments ()