Bloomington plan commission lawsuit: Appeals court has almost all papers for decision on standing

In the lawsuit filed last year over a rightful appointment to the Bloomington plan commission, a responding brief was due on Friday to the court of appeals.

It came from would-be commissioner Andrew Guenther and would-be appointing authority, GOP county chair William Ellis.

Their brief responded to the city of Bloomington and mayor John Hamilton’s initial substantive filing with the court, which was made on Jan. 21.

The city’s brief outlined why Bloomington thinks the court of appeals should overturn the lower court’s ruling, which was in favor of Guenther and Bloomington, and denied Bloomington’s attempt to dismiss the case.

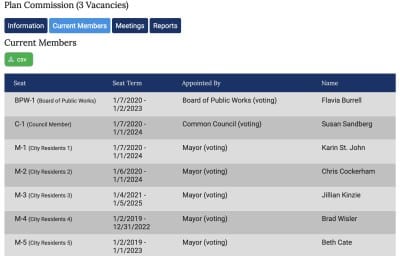

Bloomington contends that the mayor made a valid appointment to the plan commission last summer in Chris Cockerham, who is a commercial real estate broker.

The city of Bloomington could still file a reply to Friday’s brief, but would have just seven days to do that, based on the accelerated timeline granted by the court of appeals last December.

After the deadline for a reply expires, it will be up to the court of appeals to decide.

It seems somewhat unlikely that the whole lawsuit would be wrapped up before the plan commission considers the question of an upcoming citywide zone map revision.

But the timeframe for the map revision had originally called for a plan commission review in the second half of January, and that scheduling has slipped. A revised timeline for the zone map revision has not yet been announced, but it’s not expected to slide by more than a month or two.

Cockerham is currently serving on the commission.

When special judge Erik Allen denied Bloomington’s motion to dismiss the claim last August, the case was set up to proceed to the next phase at the lower court. That included the possibility that Guenther and Ellis could have asked the city to provide additional information, through the discovery process.

But before that could happen, the city of Bloomington asked the court of appeals to rule on the question of dismissal, before the lower court trial proceedings were done. It’s called an interlocutory appeal. That’s what’s going on now.

Bloomington’s position is that the mayor’s appointment of Chris Cockerham, a commercial real estate broker, is valid.

Further, Bloomington says that Guenther and Ellis don’t meet the basic threshold for bringing a lawsuit on the question. That threshold is called legal “standing” to bring the case.

Because Guenther and Ellis don’t have standing, Bloomington says, the case should be dismissed. The lower court said Guenther and Ellis do have standing.

Based on word count, Guenther and Ellis’s brief is focused more on the pure question of standing than Bloomington’s. Guenther and Ellis’s brief includes 32 mentions of “standing” compared to 15 mentions in Bloomington’s brief.

The difference in word count stems in part from the fact that in some places, Bloomington cites a case as precedent with a conclusion from a case, without discussing it in detail. In their response, Guenther and Ellis take up the specific fact pattern of the case, so they wind up writing the word “standing” more often.

For example, Bloomington quotes the opinion from a 1993 case called City of Gary v. Johnson: “…a private person may bring a quo warranto only if he claims an interest on his own relation or a special interest beyond that of a taxpayer…”

Guenther and Ellis describe the facts of City of Gary v. Johnson: “Thomas Johnson brought a writ of quo warranto action as a ‘private citizen and taxpayer’ in an effort to remove a Councilman from office and void City resolutions voted upon by said Councilman. The court of appeals reversed, concluding that Johnson did not have standing…”

The key difference between their case and City of Gary v. Johnson is that Johnson was not laying claim to the councilman’s seat, Guenther and Ellis say. It is Guenther’s stake in the plan commission’s seat that makes the two cases different, and gives Guenther standing, according to Guenther and Ellis’s brief.

Bloomington’s arguments based on a lack of standing have a certain nexus with the questions of law in the case. So extended passages of their arguments don’t necessarily include mentions of the word “standing.”

A key question of law in the case involves a state statute that defines what political party affiliation means for a partisan-balanced board like the city plan commission.

The city’s position is that state law allows for someone to serve on a partisan-balanced board, even if they don’t have a party affiliation.

Monroe County Republican Party chair William Ellis interprets the law in a different way. Ellis says the effect of the statute is to require someone appointed to a partisan-balanced board to pick a side—they have to have some party affiliation or other.

Lacking a party affiliation was Nick Kappas, who held the disputed plan commission seat through 2019, but was not re-appointed at the start of 2020.

Because Kappas had no party affiliation, but was required to have one, Ellis contends, the Republican party affiliation of Kappas’s predecessor decides the question of the appointing authority in favor of Ellis, because the mayor left the seat vacant for more than 90 days.

Kappas’s predecessor was Chris Smith, a Republican.

Friday’s brief from Guenther and Ellis gives a short response to Bloomington’s argument that involves First Amendment concerns, but says that it should have been raised with the trial court, and can’t be added now in the arguments to be considered by the court of appeals.

Comments ()