Bloomington plan commission OKs Hopewell South rezone for city council consideration, adds accessibility oversight

Bloomington’s plan commission voted to recommend rezoning 6.3 acres for the Hopewell South PUD, clearing the way for nearly 100 smaller, lower-cost homes. Commissioners added a condition to strengthen accessibility oversight and disability-community input. It will next be heard by the city council.

The Bloomington plan commission voted Monday night (Feb. 9) to give the city council a positive recommendation for a rezone of the first major housing phase of the Hopewell redevelopment.

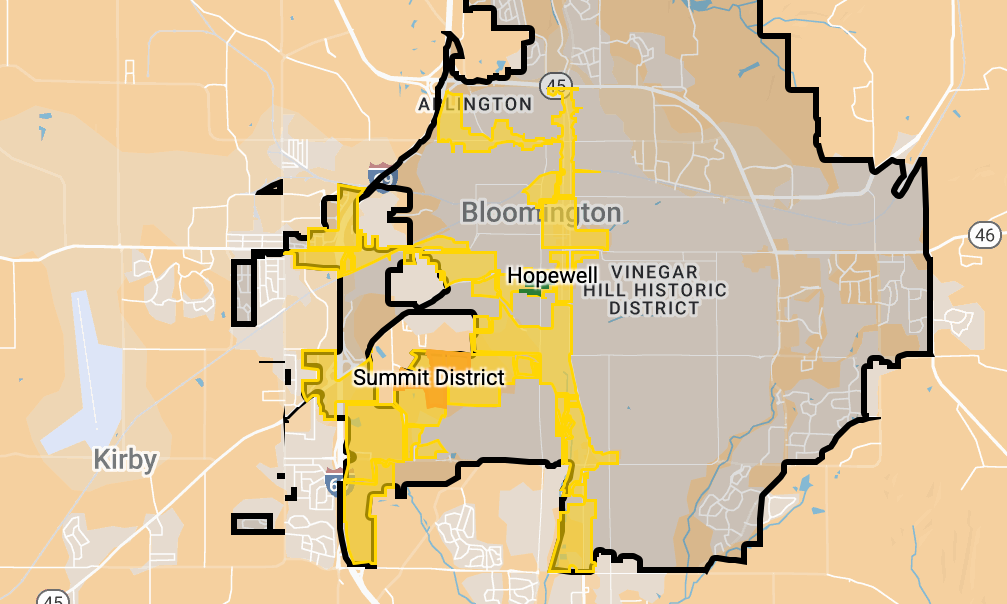

The rezone is for the Hopewell South PUD (planned unit development), which includes three blocks south of 1st Street in the area of the former IU Health hospital site, at 2nd and Rogers streets. The area includes the block where the former Bloomington Convalescent Center building stands, which the city of Bloomington is now eyeing as a possible rehab reuse project to house a police headquarters.

The plan commission’s recommended PUD comes with an added condition aimed at strengthening accessibility and accountability.

The rezone petition considered by the plan commission came from Bloomington’s redevelopment commission (RDC), which is the legal owner of the real estate.

The intended outcome for Hopewell South is for a homeownership‑focused, mixed‑income neighborhood with a wide range of housing types and experimental street designs.

Hopewell South PUD

It was Bloomington’s development services manager, Eric Greulich, who briefed the plan commission on the basics—it was the second time that plan commissioners had seen the petition. It was first heard in January.

Greulich told commissioners the Hopewell South PUD would rezone about 6.3 acres on the south side of 1st Street with a residential plan that includes a mix of single‑family, duplexes, small multifamily buildings, and ADUs up to 840 square feet—with essentially no internal setbacks, and no parking minimums.

The street network would extend Jackson and Fairview through the site at 48‑ft rights‑of‑way. That’s narrower than the 60‑foot standard. A central green corridor would carry a main pedestrian spine and stormwater detention, with additional underground detention under the Block 8 parking lot (with the former convalescent center building).

The “special” PUD elements include two narrow 20‑foot “lanes” (non‑standard cross‑section but fire‑code compliant) that function as access drives rather than full streets, and the ability to plat lots that don’t front a public street, with access only from internal walkways.

Providing advocacy for the proposed rezone was consultant Alli Quinlan, with Flintlock LAB, who described the PUD as a way to “pilot” new approaches to small‑lot urban housing that can’t be achieved under Bloomington’s existing R4 zoning.

Under current rules, Quinlan estimated the three blocks could hold roughly 28 homes with an average market price around $425,000. By using the PUD to shrink right‑of‑way widths, allow smaller lots, and introduce modest multi‑family buildings, the revised plan would support just under 100 homes with an average modeled price around $270,000, based on recent Bloomington sales data, according to Quinlan.

Quinlan told commissioners that the biggest savings come from letting more, smaller homes share the land and infrastructure costs.

The mix is planned to include: small detached single‑family homes, including studio and one‑bedroom “starter” houses; attached units (duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes); a pair of small 12‑unit multi‑family buildings; accessory dwelling units (ADUs) up to 840 square feet, with relaxed owner‑occupancy rules.

A pre‑approved “housing catalog” of designs is intended to streamline building permits and support small, local builders who might construct “a few at a time,” backed by training from Incremental Development Alliance.

Under Bloomington’s Unified Development Ordinance (UDO), there’s a qualifying standard for PUDs that requires a portion of homes in a PUD to be income‑restricted. In the Hopewell South PUD, there’s a commitment to these two elements:

- at least 50% of total units affordable to buyers under 100% of area median income (AMI), and

- at least 15% of total units “permanently income limited” to households under 120% of AMI.

Executive director of the RDC, Anna Killion-Hanson, said the PUD locks in the standards but doesn’t require deed restrictions as the only tool to achieve the standards. The tools under discussion include: “silent” or forgivable second mortgages tied to land value; shared‑equity structures; rights of first refusal held by the city or RDC.

Bloomington mayor Kerry Thomson, who attended Monday’s plan commission meeting, stepped to the mic to underscore her own skepticism about deed restrictions: “Deed restrictions are poison pills for getting houses developed, because you can’t resell them.” Thomson said, “I’m serious about looking at—as we look at our UDO changes—how do we ensure some affordability without a deed restriction?”

Accessibility and visitability

From the public mic came several comments from residents with mobility impairments and members of the city’s council for community accessibility (CCA), who said that the city is poised either to set a national example or to repeat decades of exclusion.

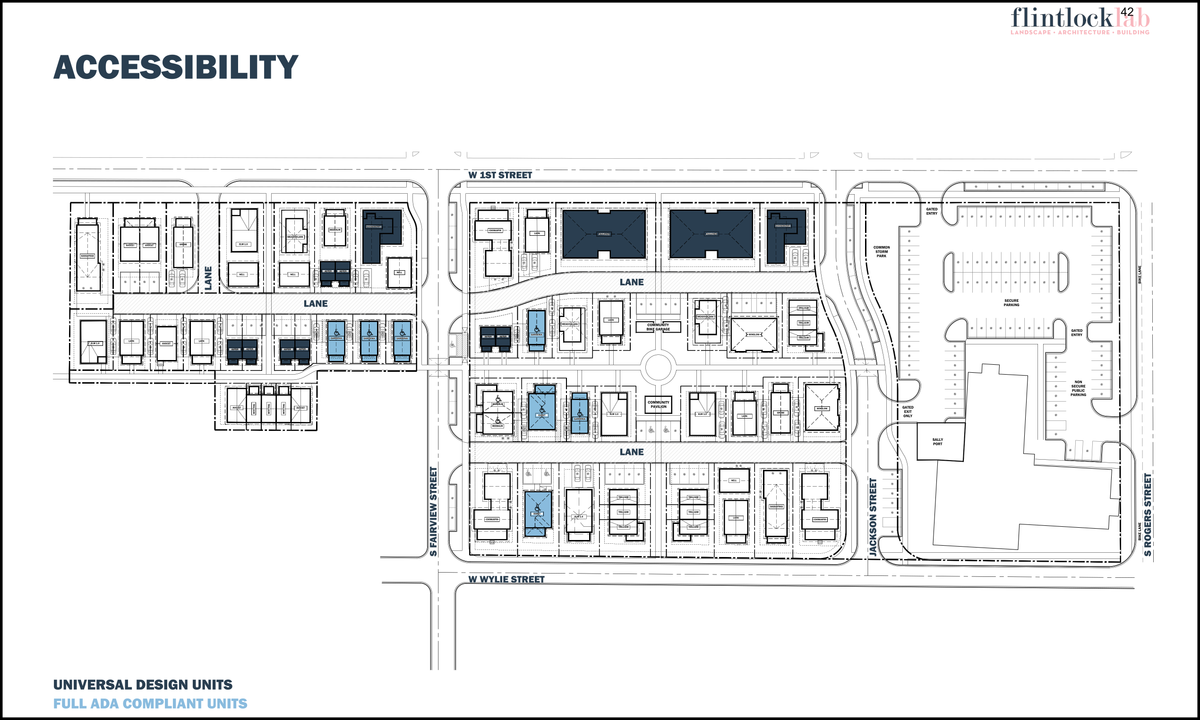

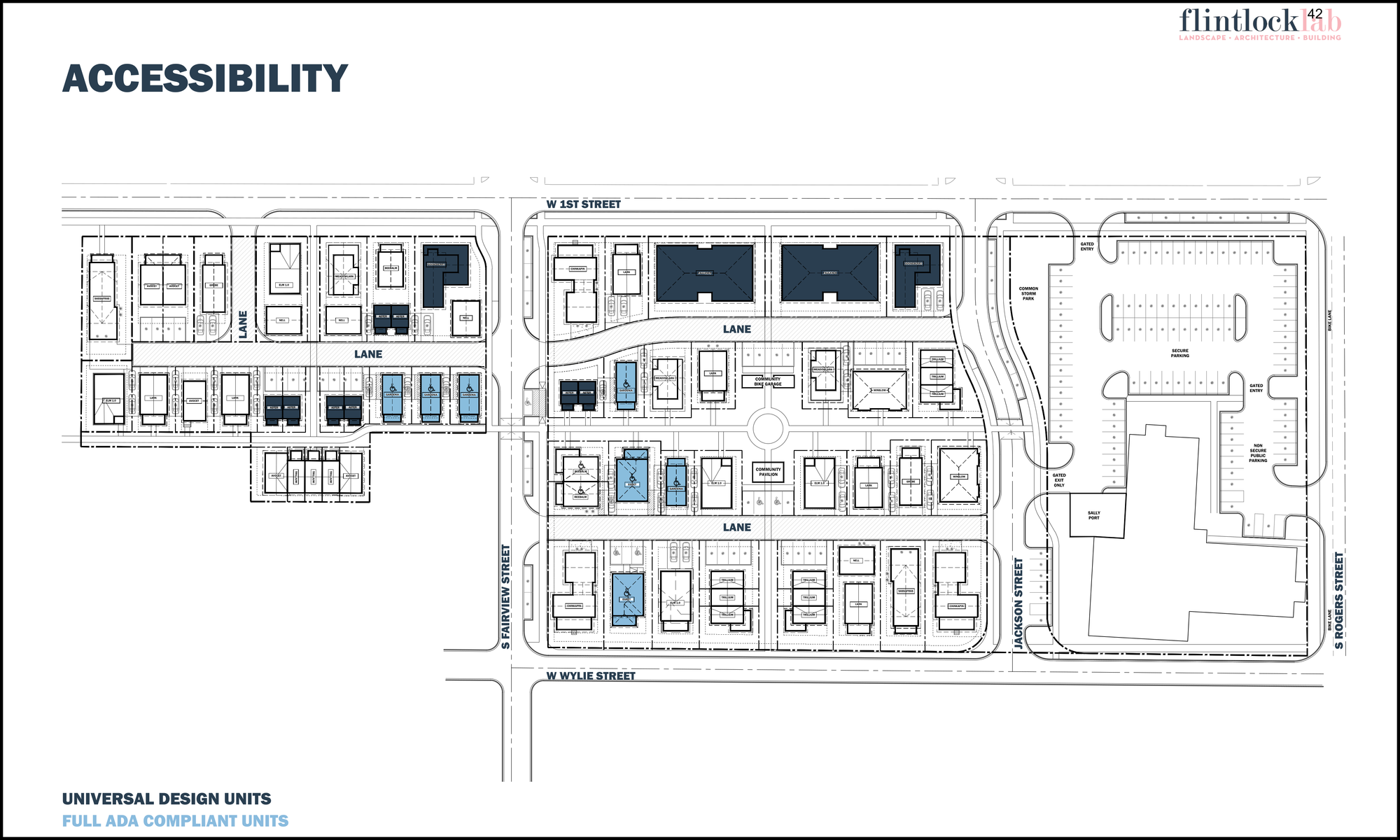

Quinlan, the Flintlock LAB consultant, laid out two tiers of accessible units:

Full ADA (ANSI Type A) units (light blue on the diagrams):

- zero‑step entry (typically from the parking side)

- larger, fully turn‑around bathrooms with grab bars, curbless showers, and shower seats. wider hallways and doors

Fair Housing Act (ANSI Type B) units (dark blue on the diagrams):

- step‑free entry to the unit

- 30-inch by 48-inch maneuvering space at fixtures, but not full five‑foot turnarounds

- more typical residential bath layouts that are “adaptable” but not fully accessible from day one

In total, the Hopewell South PUC proposes about 29% of units as either ANSI Type A or Type B, which is better than the city’s current 20% universal‑design minimum. Quinlan said that raising the percentage for Hopewell South to more than 29% would reduce the total unit count and drive up average prices, because fully ADA units have to be single‑story, and require more square footage per bathroom and hallway.

Quinlan said she had looked at a scheme that was as high as 40% accessible, but that reduced the overall units by 15. “We were trying to balance that, and find a good middle ground between accessibility and affordability,” she said.

About grading, Quinlan said the slopes and fixed street elevations make full‑site ADA compliance technically and financially difficult. She said that in her professional experience it would not be possible to grade the entire site with switch‑back ramps in a way that is ADA compliant.

From the public mic, long‑time wheelchair user Susan Seizer drew a stark contrast between her own retrofit experience and what could be done from the very start at Hopewell: “When we bought our house, it had four concrete steps to the front door,” she said, and “to make it accessible, we had to build a 30‑foot concrete ramp.”

Looking at the preliminary house drawings—which all showed steps at the front door—she asked: “Why put stairs in the entrance ways of new home constructions? Is there anything that prevents grading the site for no‑step entrances?” Seizer urged the city to build visitability (at least one step‑free entrance and a usable main‑floor bathroom) into all houses, not just a subset of them.

CCA member Karin Willison emphasized the scale of disabilities nationwide: “One in four people in the United States has a disability. We should be in every important conversation about every issue that affects us. We shouldn’t be an afterthought.” Willison criticized bathroom layouts shown in the packet as not truly usable for wheelchair users and warned about future renovation costs.

Willison said, “Accessibility should be the default, not the exception. The Hopewell South PUD should reflect these values and ensure that people with disabilities can be meaningful partners with the city as the neighborhood takes shape.”

Another CCA member, Lesley Davis, questioned why only 29% of the units are slated to be either fully accessible (ANSI Type A) or visitable (ANSI Type B). “If 29% of the homes are slated to be either visitable or fully accessible, is there a reason why a larger percentage of the homes cannot meet the standard of being step-free in some entrance?” Davis asked. “Who does it hurt to not have steps, if that’s topographically feasible?” she asked.

Davis urged approval of the Hopewell South PUD only with explicit wording about monitoring and engagement: “We think you should approve the PUD, but with added enforcement, verification or monitoring language to ensure accessibility and or visitability outcomes.”

Killion-Hanson described the stakes involved: “Bloomington is the most housing cost‑burdened metro area in the state of Indiana,” she said. She added, “Seventy-two percent of Bloomington jobs are filled by workers who live outside the city—this is not theoretical.” Killion-Hanson said: “It’s a housing crisis that is already reshaping who can live, work and remain in our city.”

Redevelopment commissioner Randy Cassady, who spoke from the public mic as a private citizen with a grandson who “will never walk,” pledged to advocate for access from within the RDC: “You have an advocate on the RDC. That’s me as an individual.”

Responding to some of the public commentary, Killion-Hanson offered a note of caution about local geology and how much can be achieved with grading: “We live in an area that has quite a bit of karst. Karst can limit grading. So there’s other considerations that you don’t know until you get out there.”

Added condition: a formal role for disability community

Reflecting the weight of the public commentary, commissioners voted to add a new, tenth condition of approval before recommending the PUD to the council.

The condition requires that, before any primary plat or final plan is approved, the petitioner must place in the project record written documentation of how visitability and accessibility were evaluated, and how people with disabilities were engaged in that process.

Commissioners and staff noted that the tenth condition of approval effectively formalizes ongoing involvement of the city’s council for community accessibility and other advocates as the housing catalog and grading plans are finalized.

The original nine conditions of approval recommended by the planning staff and agreed to by the RDC covered oversight and sequencing of the project’s build-out, requiring plan commission review of Block 8 (with the former convalescent center building), while delegating other approvals to staff, mandating compliant drainage and stormwater plans, water-pressure and fire-flow calculations, final architectural details, bicycle parking, pedestrian-scale lighting, limits on new drive cuts, and a phased schedule for installing roads, utilities and other infrastructure.

A separate, eleventh condition directs staff and the petitioner to work with the city council’s appointee to the plan commission, Hopi Stosberg to clean up cross‑references, definitions, and technical language in the PUD ordinance before it reaches the City Council.

Plan commissioner comments

Stosberg, who had been sharply critical of the drafting errors, ultimately voted yes after the eleventh condition for approval was added—she said she is “super supportive” of the basic concept of the Hopewell PUD.

Patrick Holmes was supportive of the PUD but had some qualms about how deed restrictions, which are required in the city’s current UDO to ensure permanent affordability, might be relaxed and who would have the legal authority to relax them.

Steve Bishop stressed that the Hopewell PUDC is not supposed to fix everything all at once: “This is not supposed to be a housing panacea for Bloomington. It is a prototype. It is the very first version of something that we intend to replicate successfully in better iterations over time.”

Jillian Kinzie acknowledged Stosberg’s concern about some sloppiness in the drafting, but said, “I share the concern and am disappointed that we don't have something that is more buttoned up in that way, but I also don't want to hold this up.”

Andrew Cibor, who serves on the plan commission in his role as city engineer said he was generally supportive of the Hopewell South petition, but noted as a matter of process that it would be important that the added tenth condition on accessibility should be agreed to by the petitioner. At that point, Bloomington mayor Kerry Thomson stepped to the mic to say she agreed with the condition.

Tim Ballard, a real‑estate professional, framed his support of the rezone as a necessary move in a deepening housing crisis resulting from the fact that projects like Hopewell South had not yet come forward.

About the Hopewell PUD, he said, “We need this as a tool to work within the confines of the UDO, to bring housing that can be attainable to fruition.” He also pressed for robust public education about title and affordability restrictions to avoid any “legal quagmire” for future buyers.

The Hopewell South PUD will next be heard for a final decision by the Bloomington city council.

Comments ()