Bloomington residents get some updates on leaden ashfall from fire department training

Keep children and pets away from the ash and burned paint chips that fell out of the smoke plume from a fire that Bloomington’s fire department set at 1213 High Street on Friday.

That’s the advice that local health officials gave last Friday about the ash from the plume.

It’s the same advice that was relayed by the fire department in a news release this Wednesday. On Friday, the fire department burned the house to the ground, after conducting a week-long series of training exercises involving smaller fires, each of which were extinguished.

The ash and burned paint chips are now confirmed by independent tests to contain lead. That’s consistent with the testing that’s been done on pieces of trim from the vintage 1951 house that was burned.

The light breeze on Friday took the ash westward.

Matt Murphy, who lives about two-tenths of a mile west of the burn site, did the first tests for lead, using an over-the-counter kit from 3M. Murphy tested the ash almost immediately after it started landing on his property. He’s a contractor and knew exactly where to buy the kits—Bloomington Paint and Wallpaper.

Murphy’s results have since been confirmed by at least three different entities: the laboratory headed up by Gabriel Filippelli, who’s a biogeochemist and director of the Center for Urban Health at IUPUI; environmental scientists at the Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM); and staff with Bloomington’s housing and neighborhood development department (HAND).

The city’s Wednesday evening news release was sent at the same time as a Zoom video conference was getting underway, which was organized for neighbors by councilmember Dave Rollo. The District 4 representative lives near the burn site.

Over 100 people were visible in the participants panel of the Zoom call. Invited by Rollo to participate was Indra Frank, who’s environmental health and water policy director for the Hoosier Environmental Council.

Frank responded to a question about homegrown food in the area of the ashfall. Frank advised, “If you happen to have any vegetables still in your garden, at this point, I wouldn’t eat them.”

Frank added, “If soil gets contaminated with lead, the biggest concern is for root vegetables.” That’s because the soil particles cling to those roots. Other types of vegetables that would be of concern, said Frank, are greens that have a “hairy” surface on them, because they will hold on to soil particles and they won’t wash off very well.

Frank advised that in areas where soil has been contaminated with lead, clean soil should be brought in for raised beds to use for any vegetable gardening. That’s consistent with the advice on vegetables that came from Monroe County health administrator Penny Caudill, in response to an emailed question from The B Square.

The advice from Frank and other experts on the call was for people to remove their shoes when coming in from outside. They should also wipe off their pets’ paws when they come back inside after being out in areas where ash could have fallen. People are also encouraged not to run leaf blowers or lawn mowers—to prevent creating dust with lead particles that can be inhaled or ingested.

Frank said, “Lead gets into the human body, either from accidental ingestion of dust or from inhalation. It’s my understanding that some can soak in through the skin, but that would be to a much lesser extent.”

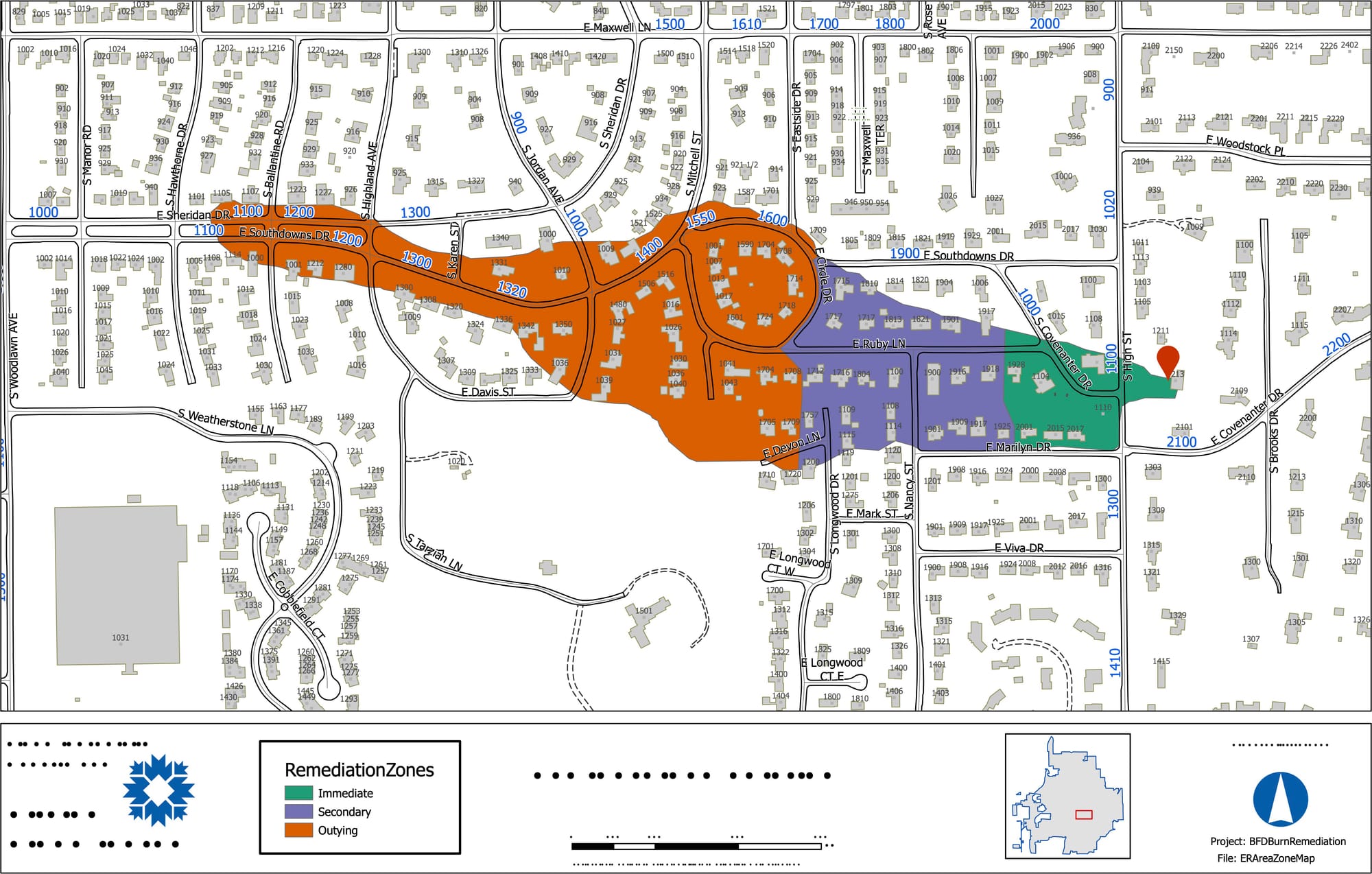

The exact extent of the leaden ashfall is still not pinned down, but some progress is being made towards mapping it out. Included in the city’s Wednesday release, is a map that integrates IDEM and city HAND data to give an idea of where the ash and paint chips are believed to have fallen.

The ashfall areas on the city’s map are shaded with three colors and a legend that reads: Immediate, Secondary and Outlying. Responding to an emailed question from The B Square, Bloomington fire chief Jason Moore indicated that the different areas on the map were classified based on the volume of visible debris.

According to Moore, those areas also serve to prioritize remediation for the contractors who have been hired. The initial contractor, which was engaged last Saturday to do remediation work, backed out.

Two other different contractors have now been brought on board. One is the Indianapolis-based Environmental Assurance Company, Inc. (EACI). According to the city’s Wednesday news release, EACI started cleanup and remediation on Tuesday afternoon (Nov. 9).

During the neighborhood Zoom call, one of the property owners who’d had their land remediated by EACI reported that no work had been done on the roof of the house. Rollo responded by saying he wanted to find out why the roof was not cleaned off. “It’s important to finish the job, it seems,” Rollo said.

Rollo ballparked the cost of remediation at $3,000 to $5,000 per house. Around 120 people have filled out the web form set up on the city’s web page for information about the 1213 High Street housing burning. That would put the cost, for just that aspect of the cleanup, at around $500,000.

On Wednesday evening’s Zoom call, one resident stated that he did not think it should be necessary for someone to fill out the web form, in order for the city to come clean the ash from the property. The city’s news release states: “Residents of properties identified within the remediation areas will be contacted by remediation crews, even if they do not fill out the form.”

A second contractor that’s been brought on board is Bloomington-based VET Environmental Engineering, LLC. According to the city’s Wednesday news release, VET is independently assessing the debris dispersal and any potential environmental impacts.

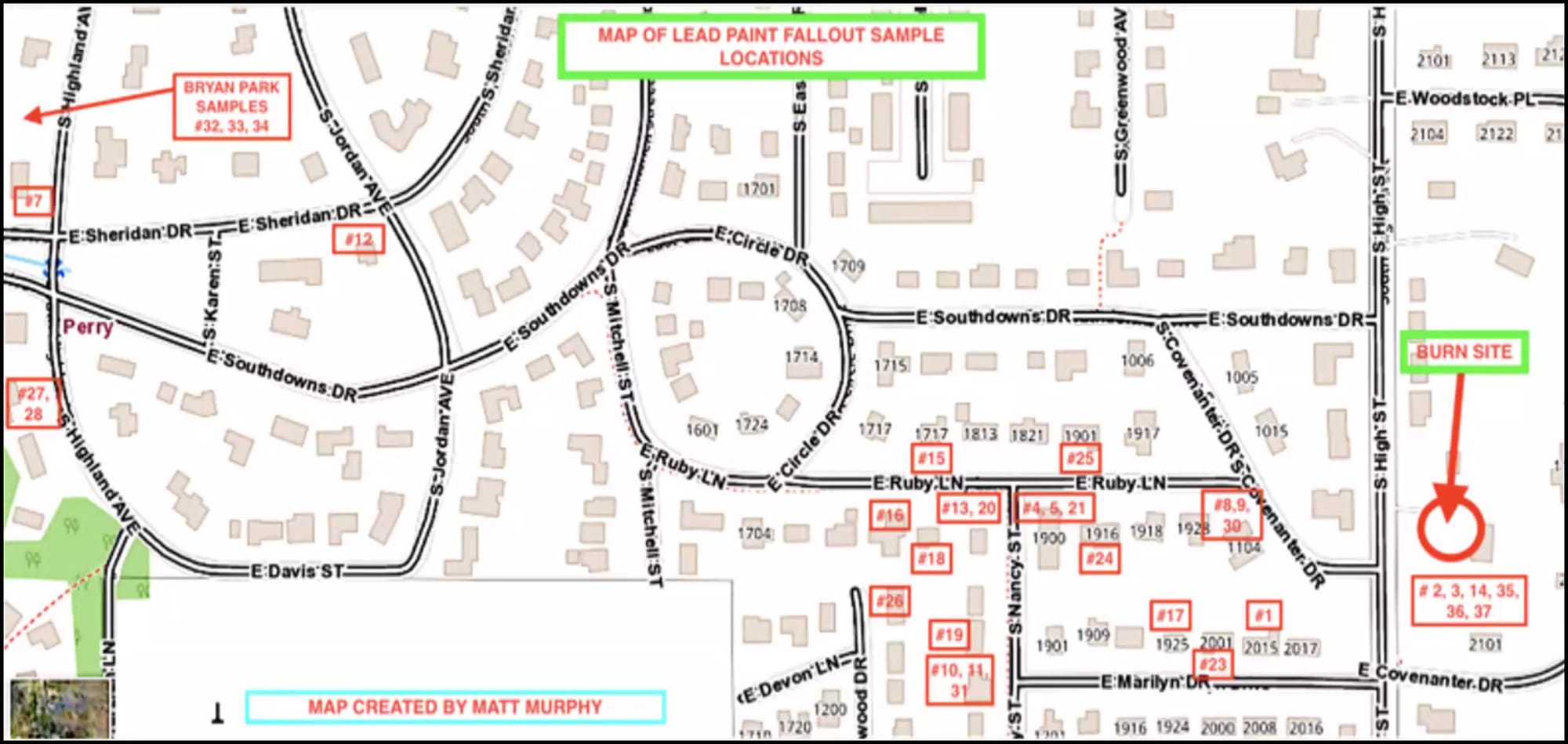

Related to the extent of the damage, at Wednesday’s neighborhood Zoom meeting, Murphy shared a screen showing places where he’d collected samples for analysis by Filippelli’s lab.

On the Wednesday evening Zoom call, two of Filippelli’s graduate students—John Shukle and Leah Wood—briefed residents on the magnitude of lead concentrations in the samples that Murphy had collected and aggregated.

Wood described some of the levels in terms of parts per million (ppm). They ranged from 84 ppm to 79,600 ppm. What Wood found remarkable was the fact that a better way to describe the samples in many cases was not in terms of parts per million, but in terms of percentage—because the concentration was so high.

The 38 samples Wood tested ranged from “below detection limit” for two samples to as high as 10.8 percent lead. The mean was 4 percent lead, and the median was 2.5 percent lead, Wood reported.

Based on the preliminary mapping of the samples, Wood said the lead “signal” does not seem to fade with a greater distance from the burn site. One of the samples farthest away is around 8 percent lead, she said.

The two grad students heaped praise on the citizen science efforts that had been made in connection with the ash fall. Shukle described how they’d be asking for more help in mapping out the extent and severity of the impact of the ash plume.

In the next few days, he and Wood are going to distribute 500 test kits in potentially affected areas. Shukle said, “We will pass them out door-to-door in communities surrounding the event. So they will either be in mailboxes, or hung on doorknobs.”

Shukle described them as “very simple kits.” He continued, “They will allow you to take multiple soil samples from around your property from any place that you would like to.”

Thursday’s forecast calls for rain. That will help keep the dust down, which will help prevent inhalation of lead particles in the short term. In the longer term, that will wash the particles into the soil, where they’ll be more difficult to extract.

Shukle said there was not a lot of risk that the lead would wash far into waterways downstream. That’s because lead tends to stay put, he said. Shukle described it like this: “Lead is typically considered very immobile in soil environments and in water environments.” He added, “Even if chips were to get into the stream, it’s very unlikely that significant quantities of dissolved lead would be moving downstream in those environments.”

Based on the interest level and remaining questions from participants, the Rollo’s neighborhood Zoom meeting could have run longer than 6:15 p.m. But it had to end at that time. The abbreviated duration was due to the start of a city council committee-of-the-whole meeting scheduled for 6:30 p.m.

Rollo expressed some frustration at the start of the neighborhood Zoom call—that mayor John Hamilton’s administration had declined his invitation to attend a potential special session of the city council.

Comments ()