Bloomington school schedule decision: MCCSC board takes control for itself, away from superintendent

The daily schedules for Bloomington’s four high schools will not change before the 2025-26 school year, and even if they do, it’s not certain the result will be a unified schedule for all schools.

What’s more, any decision on a schedule change will rest with the seven-member board of the Monroe County Community School Corporation, not with MCCSC superintendent Jeff Hauswald.

That’s all the result of action by the MCCSC board at its regular monthly meeting on Tuesday night. The board was split 4–3 on the question.

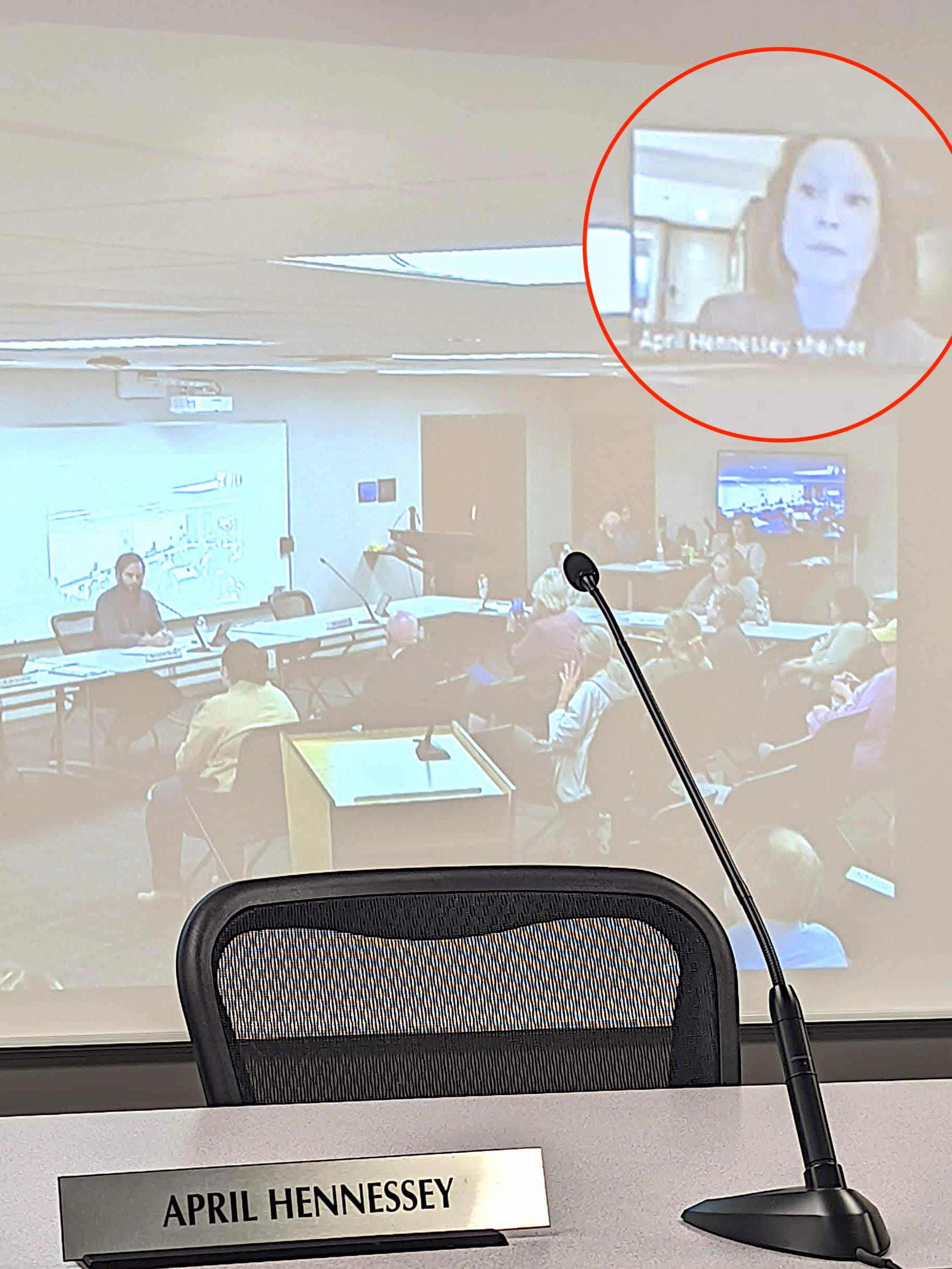

The motion to add the question to the agenda, as well as the motion to make the schedule change a board voting matter, was put forward by board vice president April Hennessey. She was participating in the meeting remotely on the Zoom video conferencing platform.

Voting for the board’s role as scheduling decision maker were: Hennessey, Ashley Pirani, Erin Wyatt, and Erin Cooperman. Voting to leave the decision making authority with the superintendent and his designees were Ross Grimes, Cathy Fuentes-Rohwer, and board president Brandon Shurr.

Hauswald had been planning to implement a unified schedule starting with the 2024-25 school year.

Right after Tuesday’s roll call vote concluded, the board’s meeting room at the MCCSC Co-Lab on East Miller Drive erupted in applause from the roughly 120 people who had crammed into the space to speak during public commentary.

Bloomington High School South operates on a trimester schedule. North operates on a semester schedule. The length of class times also differs between the schools. Also in the mix are the district’s two other high schools—Academy of Science and Entrepreneurship and Bloomington Graduation School. Unifying the schedules would mean at least some change at all schools.

Opposition to the change has been strong and organized.

Many attendees on Tuesday held the same signs they had made for the rally the previous afternoon, which was held on the southeast corner of the courthouse square in downtown Bloomington.

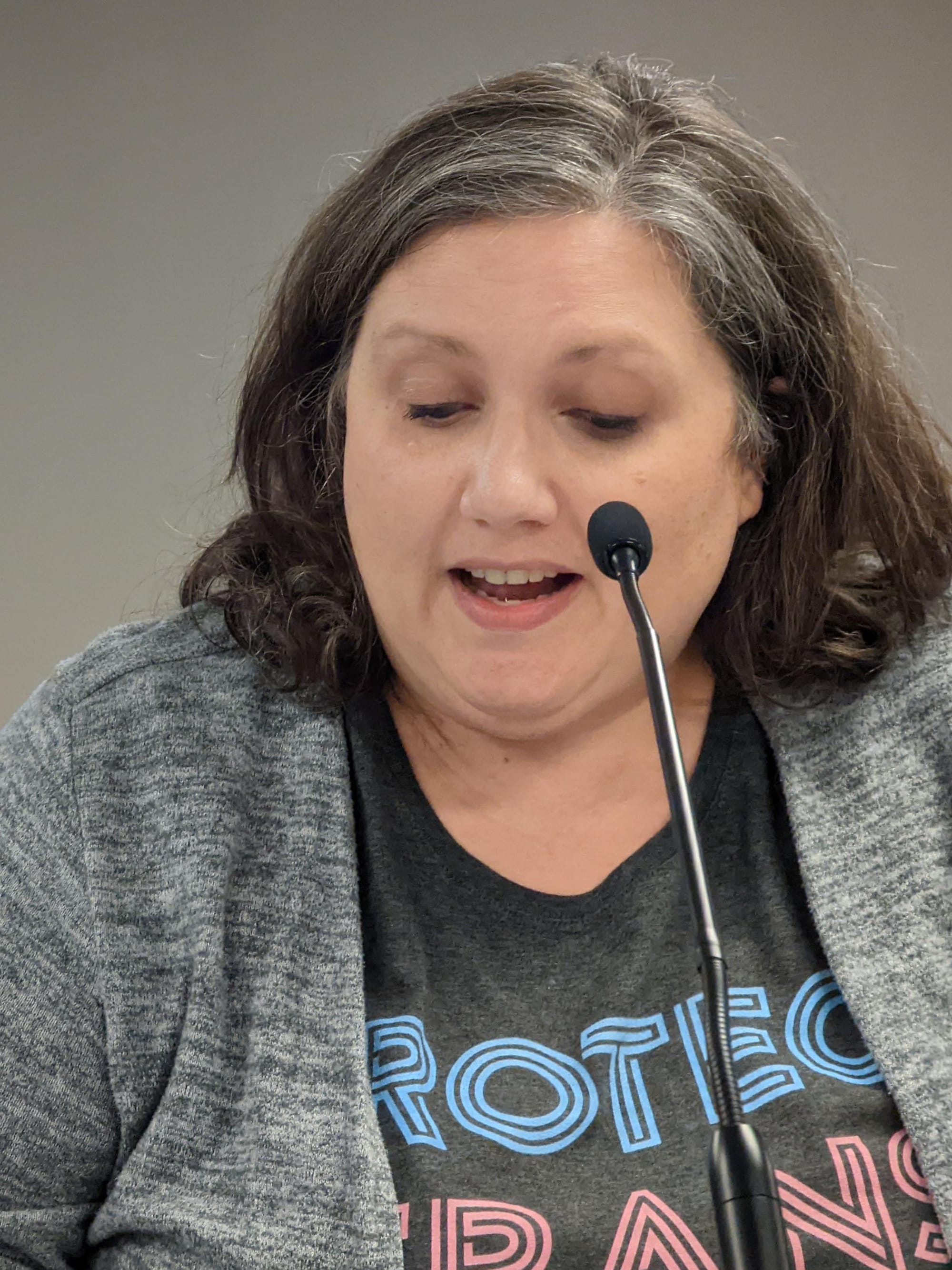

The board heard from 45 speakers in up to three-minute doses. Parents, students, and at least one teacher spoke from the public mic, making for a total of around two-and-a-half hours of public comment. Commentary was nearly universally against any change to the schedules, and was uniformly against the administration’s approach to rolling it out.

Last Friday the MCCSC administration released a memo with the main features of a unified schedule: 60-minutes classes; and a year that’s divided into two semesters, not three trimesters.

The Friday memo had caught many by surprise, because they had the impression that the MCCSC administration was still gathering information, in order to make a decision.

During Tuesday’s meeting, one attendee called out to Hauswald from a seat in the audience, “You lied to us!”

From the public mic on Tuesday, the Friday memo drew criticism because it had no name attached to it. It was characterized as a “Friday news dump.”

After the public commentary, Hauswald held firm on the basics of the plan, but conceded that the communication could have been improved. He also said transparency would be improved as the process moves ahead.

The point of the Friday memo, Hauswald said, was just to clarify some features of the new schedule, in order to counter what he described as misinformation in the community about the plan.

Hauswald reviewed some of the highlights from the Friday memo which described some of the inequities in the existing schedules that had been identified by administrators. At Tuesday’s meeting, Hauswald said that those inequities had been identified this spring.

An example given in the Friday memo, for what the administration contends is a disparate impact on those who are economically disadvantaged, comes from the participation in arts classes.

The current scheduling practice used by Bloomington High School South teachers means that while 65 percent of all BHSS students participate in arts classes, just 54 percent of students in the free/reduced lunch program do. And just 36 percent of BHSS students with disabilities take classes in the arts.

According to the Friday memo, the numbers from the last five years show there were 100 transfers between high schools with unaligned schedules. According to the memo, 55 percent of the transfers were students on the free/reduced lunch program. According to the memo, “these identified transfers were twice as likely to be Black/African-American students.”

Some of the questioning of Hauswald by board members was sharp. Pirani wanted Hauswald to explain why he thinks it’s urgent to implement a new schedule for all the high schools starting in the 2024-25 school year.

Pirani: What’s the urgency?

Hauswald: So the urgency is, we have a significant number of students right now…

Pirani: What’s the number?

[cheers and applause]

Hauswald: … I understand…

Pirnani: No, I don’t know that you do right now. I’m asking, because I have been asking repeatedly for numbers, I want to know the numbers of the students that are impacted.

Grimes voted against making the high school schedules a board voting matter, saying, “I do think [the unified schedule] addresses the equity issue.” But he had this to say about the process the administration had used: “Do I think the process, the roll out of it, was horrible? Yeah, I hate the way it was presented.”

But Grimes compared the issue to being told you have cancer. “Are you gonna wait to find the best chemotherapy? Or are you going to start your treatment now?” That analogy drew groans from the audience.

Wyatt cautioned that even if the board has the final say on the schedule, that does not mean it won’t wind up being a unified schedule.

Fuentes-Rohwer, who voted against making the high school schedules a board voting matter, also allowed that the communication had not been as good as it could have been. She put it like this: “We can always improve on communication. And oftentimes people say it’s not transparent because they feel blindsided, they haven’t seen it.”

But for Fuentes-Rohwer, the administration’s starting point, which was equity for those who have historically been marginalized, was persuasive. She said, “It’s really exciting to see very mindful, very planful, very database- and research-driven change happen in this community, with an emphasis on making sure that we don’t brush aside the fact that maybe there are systemic ways that our most historically marginalized children are not being well served.”

Cooperman said her guiding principle is the question: Is this an equity problem? The followup question that guides her thinking about the schedule change was: Is this a move towards equity?

Cooperman seemed a bit on the fence, and at one point made a motion to table Hennessey’s motion, to give the administration more time to make its case. But she wound up withdrawing the tabling motion.

Hauswald, reading the room, indicated that attendees wanted the issue settled one way or another that night.

When she introduced her motion, Hennessey reviewed some considerations about the proper roles of the board and the superintendent.

She quoted from the Indiana School Board Code of Ethics, which says that, “A school board member should honor the high responsibility that membership demands… by understanding that the basic function of the school board member is policy-making and not administrative, and by accepting the responsibility of learning to distinguish between these two functions.

Hennessey noted that Indiana Code 20-26-5-4 gives the superintendent the power to, among other things, carry out duties related to and including the making of schedules.

Hennessey quoted again from the Indiana School Board Code of Ethics: “A school board member should maintain desirable relations with the superintendent of schools and other employees…by giving the superintendent full administrative authority for properly discharging the professional duties of the position and the responsibility to achieve acceptable results.”

In that point of the code, Hennessey highlighted the phrase “acceptable results.”

For Hennessey, the part of the code of ethics that reserves certain responsibilities for the superintendent has to be balanced against the part of the code that addresses a board member’s responsibility to the community. That part reads: “A school board member should maintain a commitment to the community…conducting all school business transactions openly…by earning the community’s confidence that all is being done in the best interests of school children.”

In responding to some board questions, Hauswald described how the equity issues that had spurred the move towards a schedule change had been identified by other district administrators, based on the district’s strategic plan.

Hennessey expressed skepticism about that. She told Hauswald she thinks he initiated the schedule change. She summarized Hauswald’s description like this: “And what I’m saying here is, this entire discussion has been: the administrative team, these people, the principals, this person, that person.”

Hennessey continued, “But I believe strongly that this was an initiative that began at your behest, Dr. Hauswald, and was issued to individuals to take up. I believe that to be true.” Hennessey said she did not have a document proving her belief, but noted that some members of the community had made formal records requests of the district.

One consequence that could emerge as a result of the board’s action on Tuesday is that an unfair labor complaint could be filed by the Monroe County Education Association. Paul Farmer, who’s president of the association, told the board from the public mic that the timeframe of 2024-25 for the schedule change had been discussed with the MCEA—but not any extended timeframe as described in Hennessey’s motion.

So the MCEA would either have to object on the grounds that the proper discussion, to which the labor group was entitled, was not given, or else acquiesce, which he was not inclined to do, Farmer said. [Added on Oct. 25, 2023 at 1:50 p.m. Here’s a link to the text of an email message that Farmer sent to the MCEA membership: Farmer email.]

Farmer suggested that Hennessey’s motion could be amended simply by striking any reference to the timeframe. If the board was acting to make the school schedules a board voting matter, then the board would be able to reject any proposal for an earlier plan. The board wound up voting on Hennessey’s original, unamended motion.

Comments ()