Bloomington tightens wastewater rules, aligns local stormwater regs with state law

At its Wednesday night meeting, Bloomington’s city council updated local regulations on wastewater and stormwater by enacting two separate ordinances. Hydromechanical grease traps are added to the list of approved devices for fat, oils, and grease management.

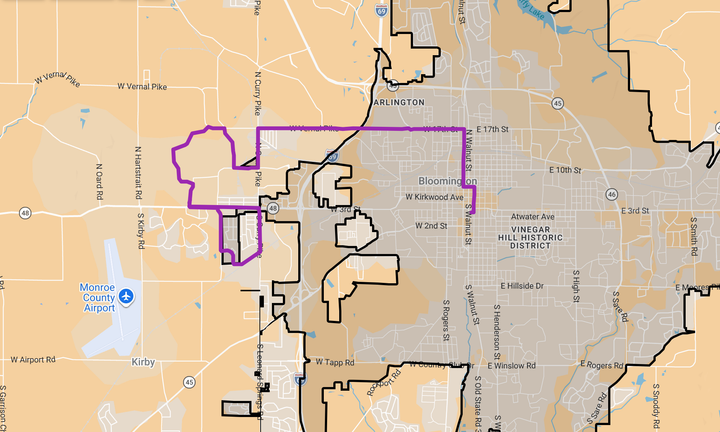

Left: Bloomington’s Dillman Road wastewater treatment plan. Right: Bloomington’s Blucher Poole wastewater treatment plant. The images are from the Eagleview module of Beacon, which is the platform that Monroe County government uses to manage GIS and property information.

At its Wednesday night meeting, Bloomington’s city council updated local regulations on wastewater and stormwater by enacting two separate ordinances.

The changes to the city’s wastewater rules were prompted in part by the relocation of IU Health’s hospital, which meant a different treatment plant is now handling the health care provider’s wastewater. Bloomington has two wastewater treatment plants—one south of town on Dillman Road and the other north of town, named after Blucher Poole. The new pretreatment program for the Blucher Poole plant means new standards citywide.

But the stormwater ordinance was a response to a new law passed by the state legislature, which restricts local governments from enforcing stormwater regulations that go beyond state requirements. Both ordinances were presented by staff from City of Bloomington Utilities (CBU)

Wastewater: industrial discharges, restaurant grease

The first ordinance updated regulations on what businesses can send into the city’s sanitary sewer system. The changes affect the city’s industrial pretreatment program, which sets limits on certain pollutants, including toxic metals. The pretreatment program requires businesses to treat wastewater before it reaches public pipes.

Steven Stanford, who is CBU’s industrial pretreatment program coordinator, told councilmembers the updated ordinance tightens local limits for four toxic metals—cadmium, mercury, selenium, and silver—based on recent recalculations required by state and federal environmental agencies. The new citywide limits reflect updated water quality standards and data from both of Bloomington’s wastewater treatment plants: Dillman Road and Blucher Poole.

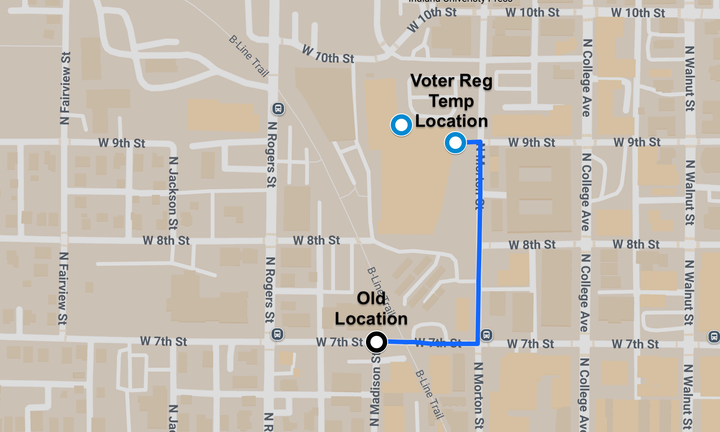

This is the first time local limits were set using both plants simultaneously, a shift prompted by the relocation of IU Health Bloomington from 2nd and Rogers streets to the east side. “Pretreatment was added to the Blucher permit because of [IU Health’s] new hospital,” according to Stanford’s memo, which notes that the old hospital was served by the plant on Dillman Road. His memo says that the lowest value calculated for each pollutant at each treatment plant was recommended by CBU as a unified local limit for the whole city.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency gave tentative approval to the updated pollutant limits in May, but required the city to formally adopt them by Aug. 13 in order to remain in compliance with federal regulations.

Another key change in the ordinance raises the minimum allowable pH level in industrial discharges—from 5.0 to 6.0. On the pH scale, 7 is neutral; lower numbers are more acidic. By raising the floor to 6.0, the city will not accept wastewater as acidic as it does now.

While the city previously followed the federal minimum of 5.0, Stanford said Bloomington’s infrastructure, which is made largely of Portland cement concrete, has shown signs of corrosion: “What I observed in our system is that we’ve got etching and corrosion visible throughout the wastewater collection and treatment system.” The new limits are meant to help with that corrosion.

Bloomington has 14 permitted industrial users. Stanford described a “polite conversation” with one of them about their pH levels. The business voluntarily adjusted its pretreatment system to target a pH of 6—at minimal cost—once it was explained that the change would help preserve both city and private infrastructure, Stanford told the city council.

The wastewater ordinance also updates rules for food service establishments that have to manage fats, oils, and grease—collectively known as FOG—before it goes down the drain. Under the newly enacted local code, hydromechanical grease traps are added to the list of approved devices for FOG management. Such traps use gravity and baffles to separate FOG from wastewater to keep it out of the sewer system. They are typically less expensive and easier to install than traditional outdoor interceptors.

On Wednesday, Stanford replied to a councilmember question about any outreach that he had done to business owners about the hydromechanical grease traps. He had not done that kind of outreach, he said, because “The only thing we’re changing is we’re adding an additional option that they can choose to use.”

Stormwater rules: Alignment with new state law

The ordinance on stormwater enacted by Bloomington’s city council on Wednesday night brings the city’s stormwater regulations into alignment with a new Indiana state law that bars local governments from imposing construction-site rules stricter than those required by the state.

Kelsey Thetonia, CBU’s assistant director for environmental programs, told the council that means the city must remove some of its previous standards, such as a requirement that disturbed land be fully stabilized within seven days. Now, stabilization only needs to be started within that timeframe.

“We are going to have to take a more defensive approach to erosion and sediment control on some sites,” Thetonia said, which means the city may have to wait for problems like runoff or sediment loss to occur before enforcement can kick in. Thetonia said, “We would like to prevent [problems] in the first place by having a good plan in place and be able to enforce it as a project progresses. But if we cannot do that, or have no way to do that because of this law, then we may have to wait until something bad happens before we can enforce ...”

Councilmember Isak Asare asked about the city’s new online system, called EPL,will help speed up the permitting process for new developments. CBU director Kat Zaiger attended the council’s Wednesday meeting and responded to Asare’s question, by describing the city’s new EPL (Enterprise Permitting and Licensing) Program. “People who apply for permits can now see where it’s at through EPL, like they do with planning permits currently,” Zaiger said.

Comments ()