Bloomington’s 2020 census count: Plot (of dots) thickens for IU enrollments, dormitories

Ten days ago, when the news broke that Bloomington’s 2020 Census count had dropped, compared to the 2010 numbers, many residents reacted with disbelief.

The leading theory for the 1.5-percent drop, from 80,405 to 79,168, is based on the fact that Bloomington is home to Indiana University’s flagship campus.

The city experienced a pandemic-related mass exodus of students right around the time the census count was taking place, in late March and April. The university delivered remote-only instruction for the rest of the spring semester.

Thousands of students were undercounted in the 2020 Census, goes the theory, which would explain why the vintage 2019 estimates by the US Census Bureau put the population of Bloomington at 86,630, or about 7,000 more than the actual count done in 2020.

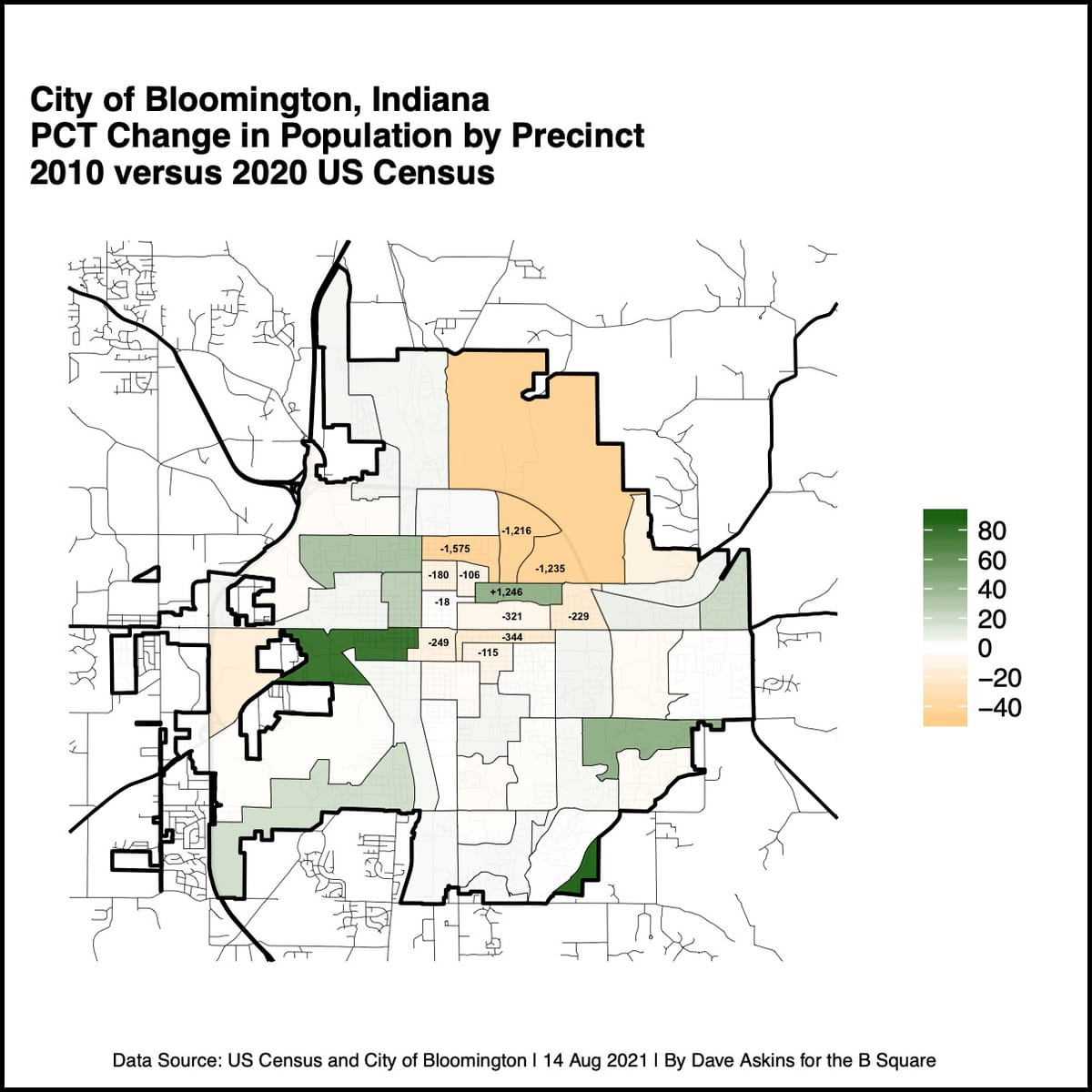

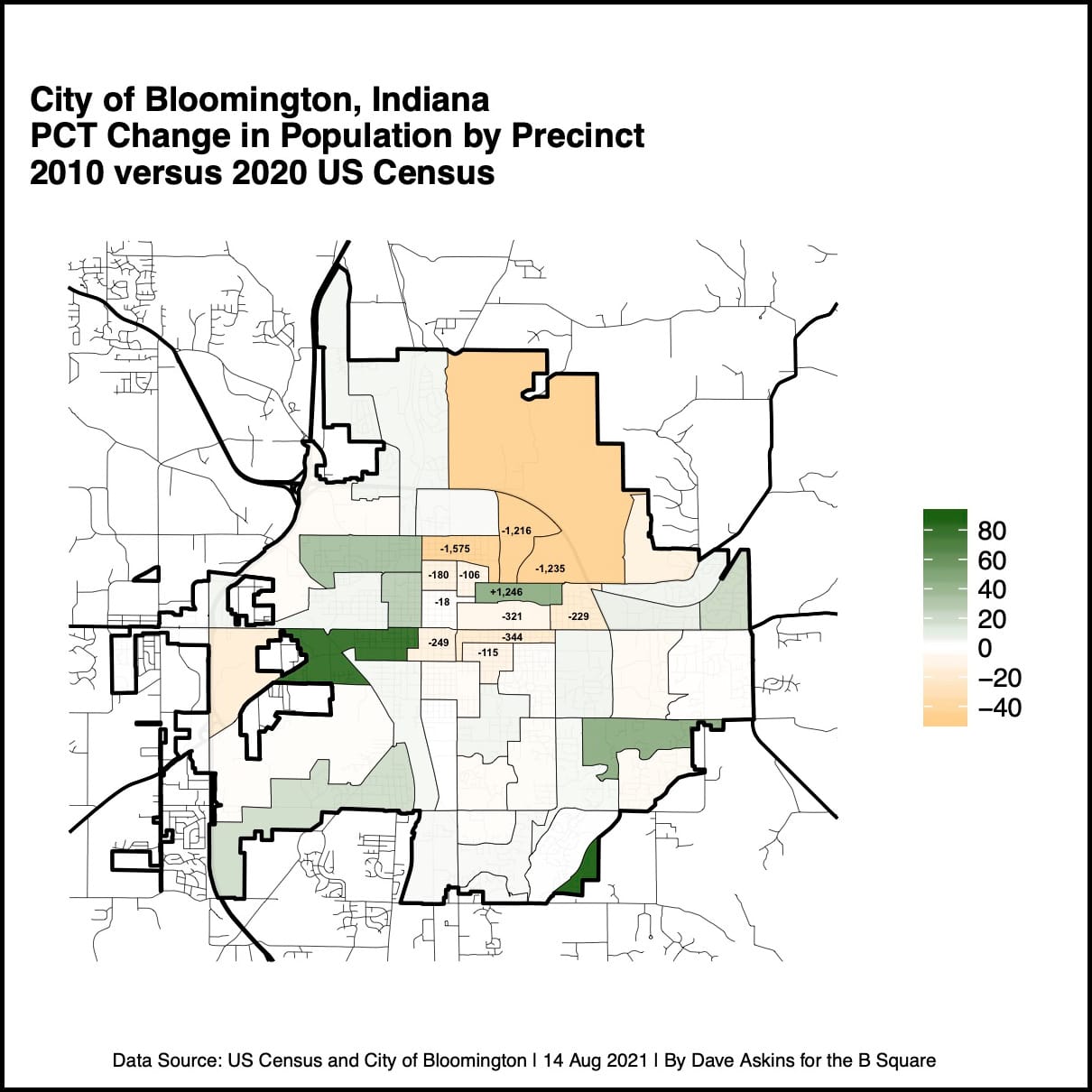

A theory based on student undercount is consistent with The B Square’s coarse-grained look at the precinct-by-precinct geographic distribution of population losses.

If students were undercounted, then that should be reflected in losses in on-campus and near-campus neighborhoods where many students live. The geographic distribution does show diminished numbers in areas on and near campus.

A different theory of that geographic distribution does not rely on the idea of a student undercount: If there were fewer students actually living in those campus areas, fewer students would be counted there.

That’s a theory that looks like it could have some support from two possible perspectives.

First, a more fine-grained look at Bloomington’s geographic distribution of census counts is a good reminder that population numbers in a small area can be dramatically affected by whether a 1,000-bed dorm complex was open or closed in 2020 compared to 2010.

Second, a look at Indiana University’s in-person enrollment trends makes it plausible that in 2020, at least a couple thousand fewer Indiana University students were living in Bloomington, compared to 2010.

Indiana University dorms

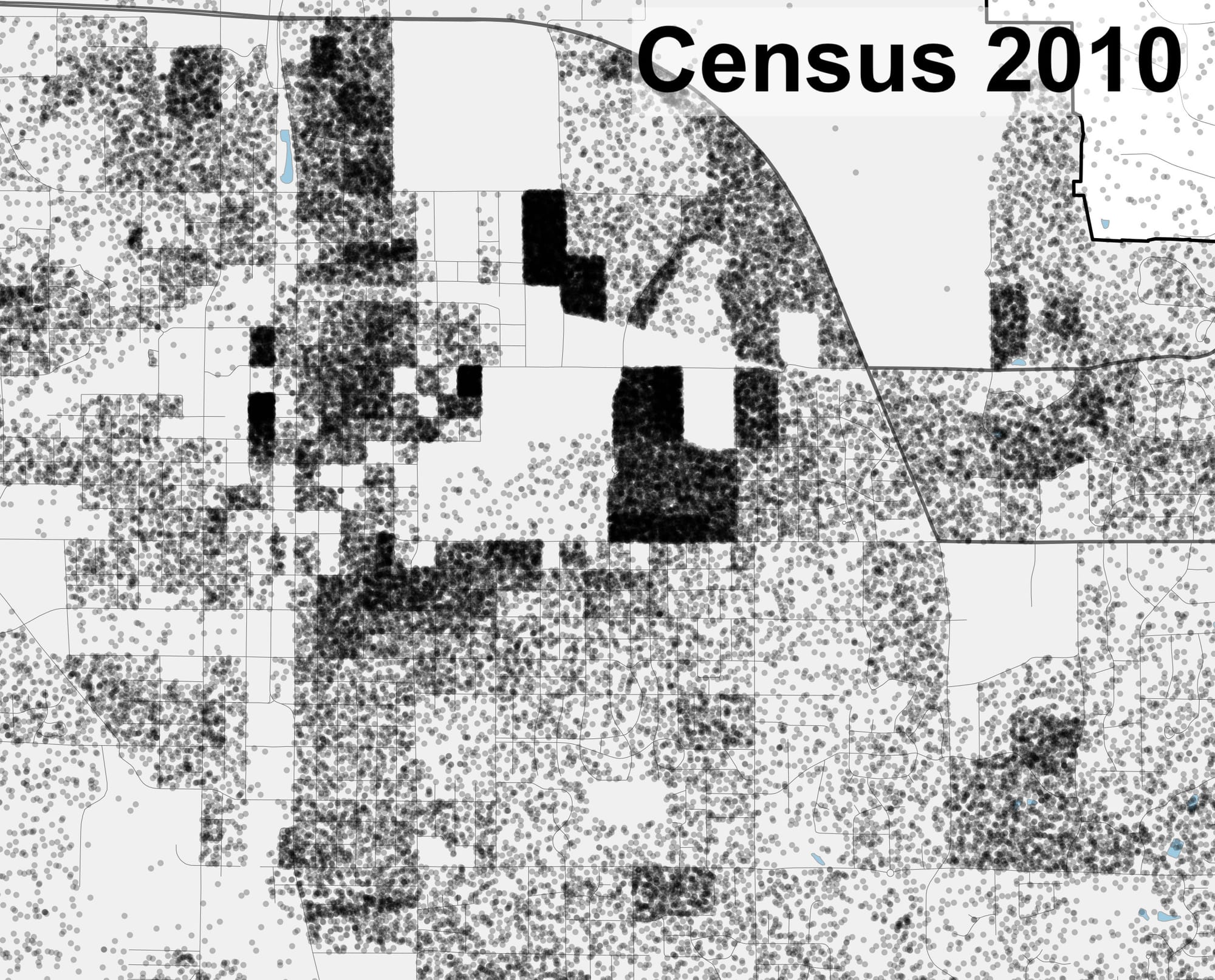

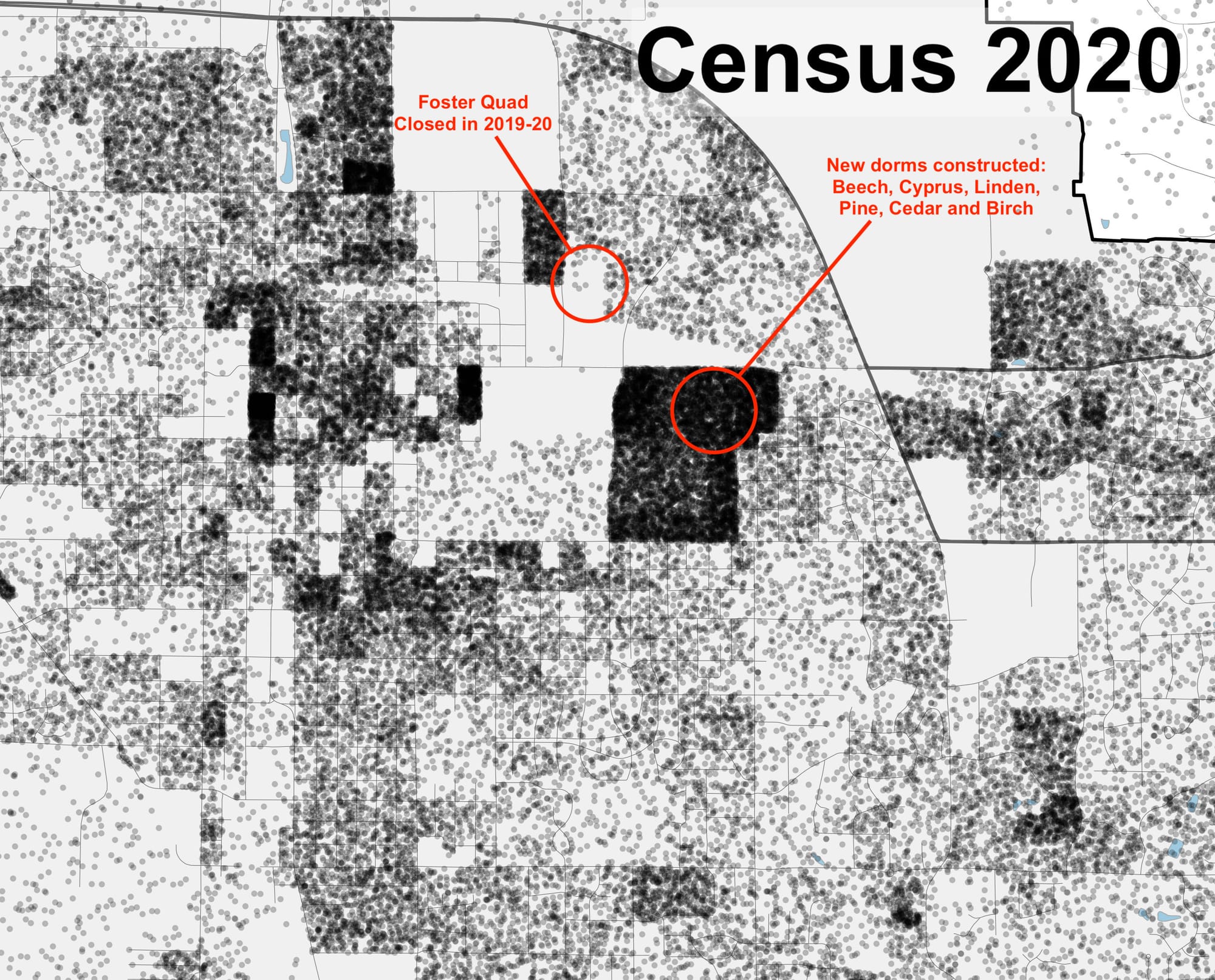

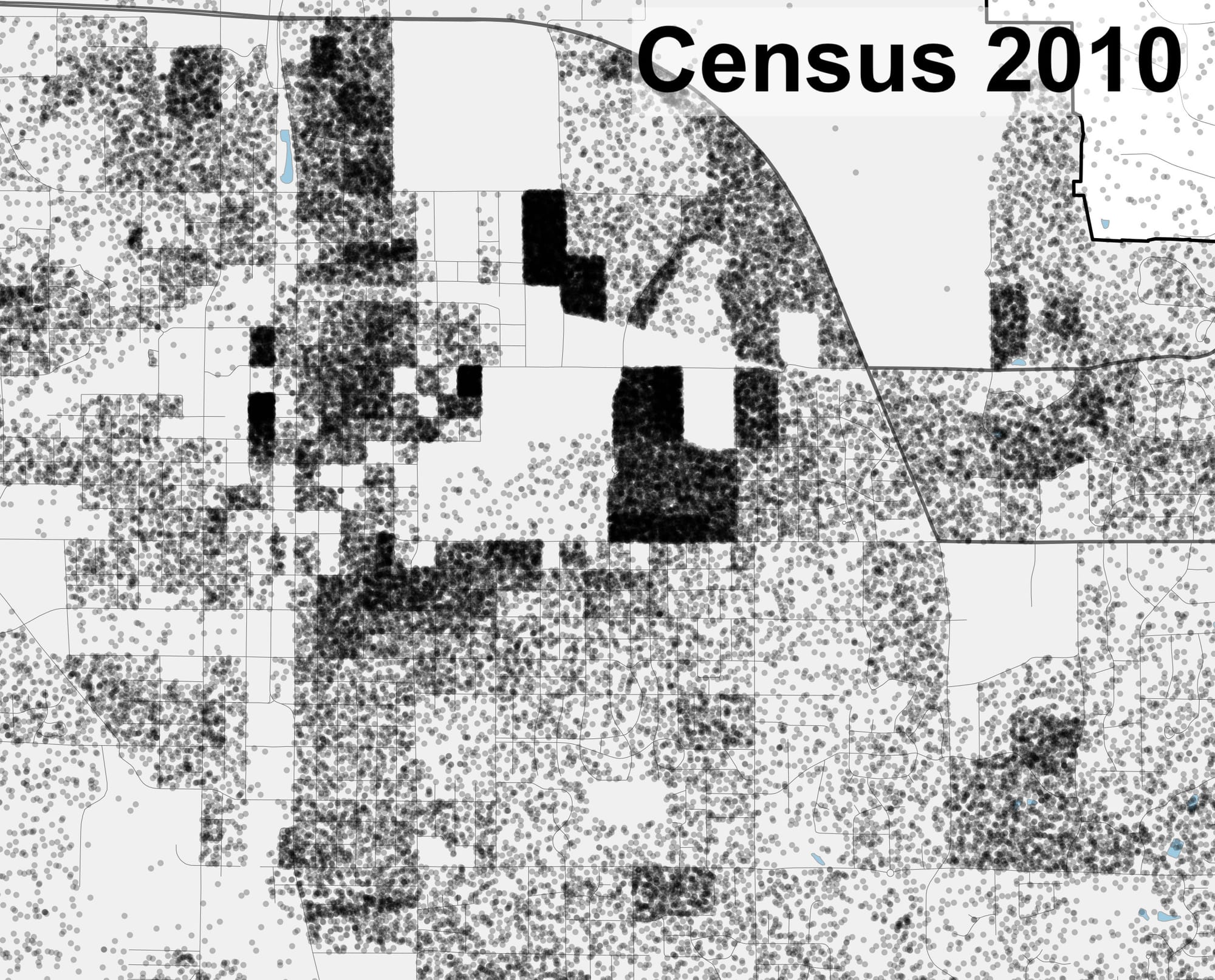

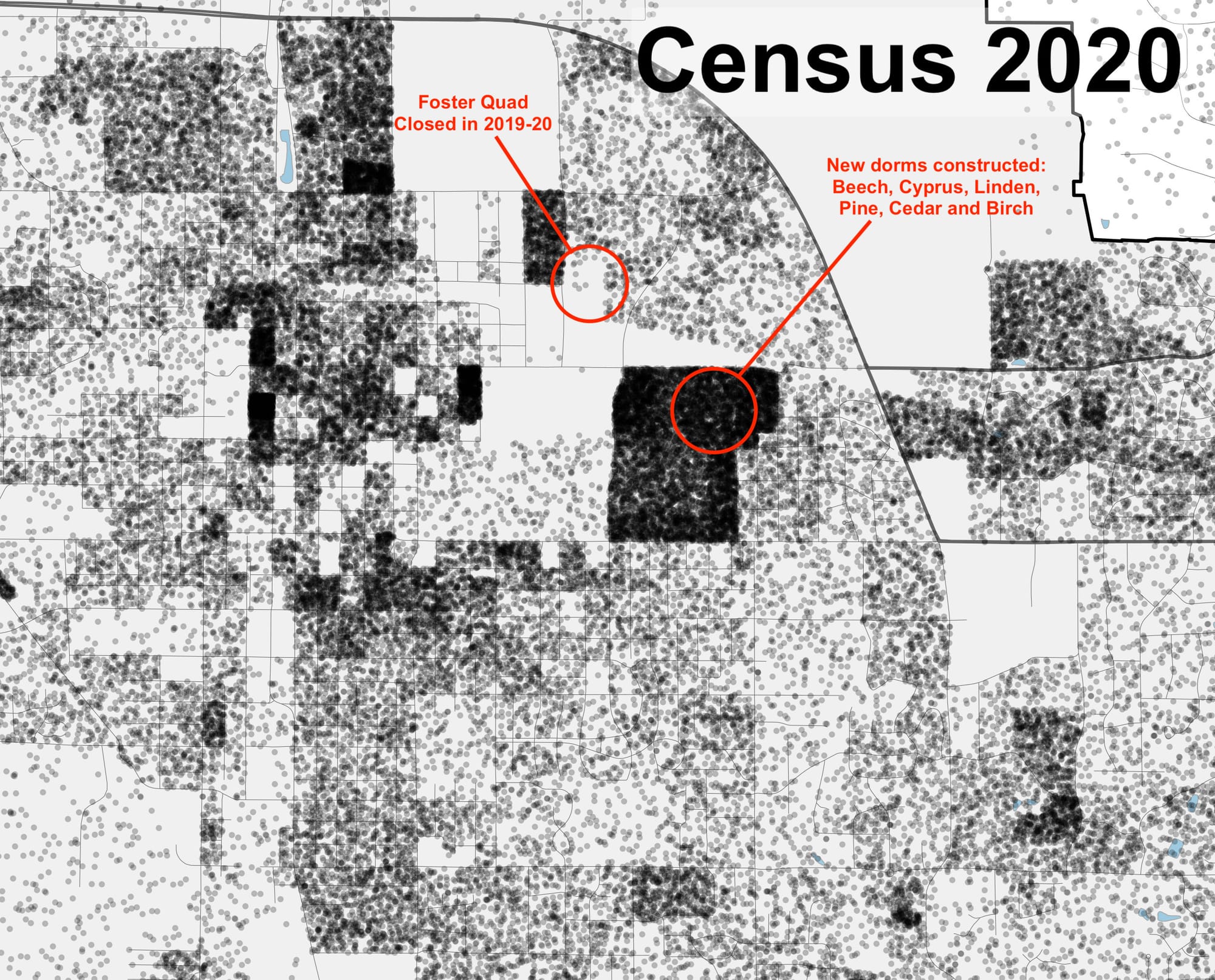

A dot-map plot (1 person = 1 dot) of counts by census block reveals two clear differences between 2010 and 2020 in the Indiana University campus area.

First, an area northeast of Fee Lane and 10th Street was densely populated in 2010, but shows no one living there in 2020.

That’s almost certainly due to the fact that Foster Quad was under renovation in 2020, but probably housed around 1,200 students in 2010.

According to IU director of media relations Chuck Carney, the university is expecting 1,154 residents for Foster Quad this fall. That squares up with the fact that the precinct where Foster Quad is located showed 1,216 fewer residents in the 2020 Census compared to the 2010 Census.

Second, an area southeast of 10th and Union Street was not populated at all in 2010 but was densely populated in 2020. That’s almost certainly due to the fact a cluster of new dorms was completed there in 2010. The halls are named after trees: Beech, Cyprus, Linden, Pine, Cedar and Birch.

The precinct where that block is located showed an increase of 1,246 in the 2020 Census count, compared to 2010.

All this supports the idea of considering the net change in the population of near- and on-campus neighborhoods—not just adding up all the decreases in those precincts that showed a decrease and calling that figure the “undercount.”

The net decrease in the count for campus and near-campus neighborhoods works out to 4,342. How does that stack up against actual student enrollment?

In-person student enrollment

Indiana University’s online data resource for enrollment trends breaks down students by “on-campus presence.”

That means it’s possible to track enrollment trends for students who are physically present, attending classes on Bloomington’s campus, compared to those who have no on-campus presence, because they’re taking classes online.

That kind of breakdown of students goes back to 2014. What about the three years before that?

According to IU’s assistant vice president for institutional research and reporting Todd Schmitz, to estimate the in-person total enrollment for those earlier years, the total enrollment could be reduced by 500-750. That’s because for those years, roughly that number were enrolled in online programs and not coming to campus.

The fuzziness on the early end of that data is made even a little fuzzier because the dataset goes back only to 2011, so it does not include 2010, which is the year of specific interest for comparing decennial census counts.

With a caveat about some fuzziness in the data, it still looks plausible that by IU’s own count, in 2020 there could have been around 3,000 fewer enrolled students in Bloomington than in 2010.

That would account for about 75 percent of the measured net decrease in on-campus and near-campus population counts between 2010 and 2020.

It still leaves room for the idea of some undercounting—but probably not the 7,000 or so that would be needed to bump Bloomington’s count to the level of the 2019 US Census estimate, which was 86,630. The margin of error for that estimate was 2,838.

More caveats

Even if the 2020 Census count was surprising to many, and the theory of a pandemic-related undercount has first-blush plausibility, it’s clear that making a persuasive case to the US Census Bureau for an undercount will require a finer-grained analysis.

One finer-grained factor that would probably need to be considered is other parts of the city where students live. Indiana University students can live wherever they like. So focusing exclusively on near- and on-campus neighborhoods leaves out the possibility that students living in other parts of town, more distant from campus, did not fill out the census form to reflect their Bloomington residency, even though they should have.

For on-campus students the university adopted a group-quarters reporting approach to the census.

A group-quarters approach basically means that the university completes the census on behalf of the student residents of the dorms.

The US Census Bureau is unlikely to see its own higher estimates as evidence that Bloomington’s 2020 actual count was too low. As a CB public information officer put it in an emailed message to The B Square: “Differences between the estimates and census counts are interpreted as error in the estimates and not the census counts.”

Could the difference between Bloomington’s prior estimates and the 2020 count derive from faulty IU enrollment data, based on a failure to distinguish between in-person and online students? No. According to the CB, “We do not use college enrollment data for this calculation.” The population estimation program uses vital statistics, property or income tax records, federal, state and county records, and other data sources.

The US Census has a process for “appealing” the counts, called the Count Question Resolution (CQR) program.

The impact of the lower numbers for Bloomington has implications for millions of dollars in federal funding allocations over the next decade.

At last Friday’s press briefing on the city’s 2022 proposed budget, Bloomington’s mayor, John Hamilton, stated, “What we’re really focused on is trying to get our arms around those [census] numbers. They’re not credible, from my perspective.”

About possible appeal, Hamilton said on Friday, “It’s a legal process. We have to figure out how we’re going to address that.”

Animation: 2010 versus 2020 Dot Map

Comments ()