Bonds for first step of Bloomington’s public housing conversion get final OK from city council

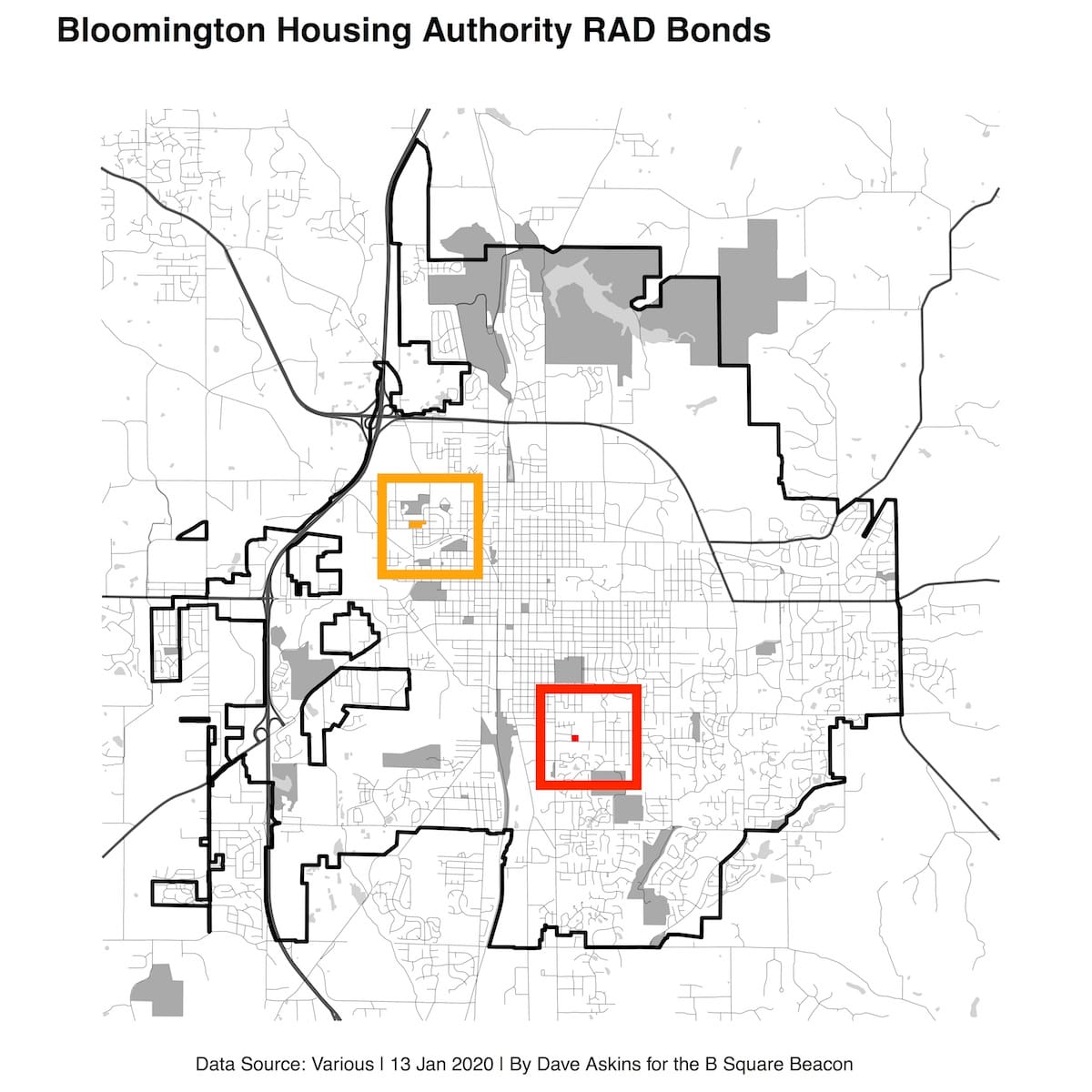

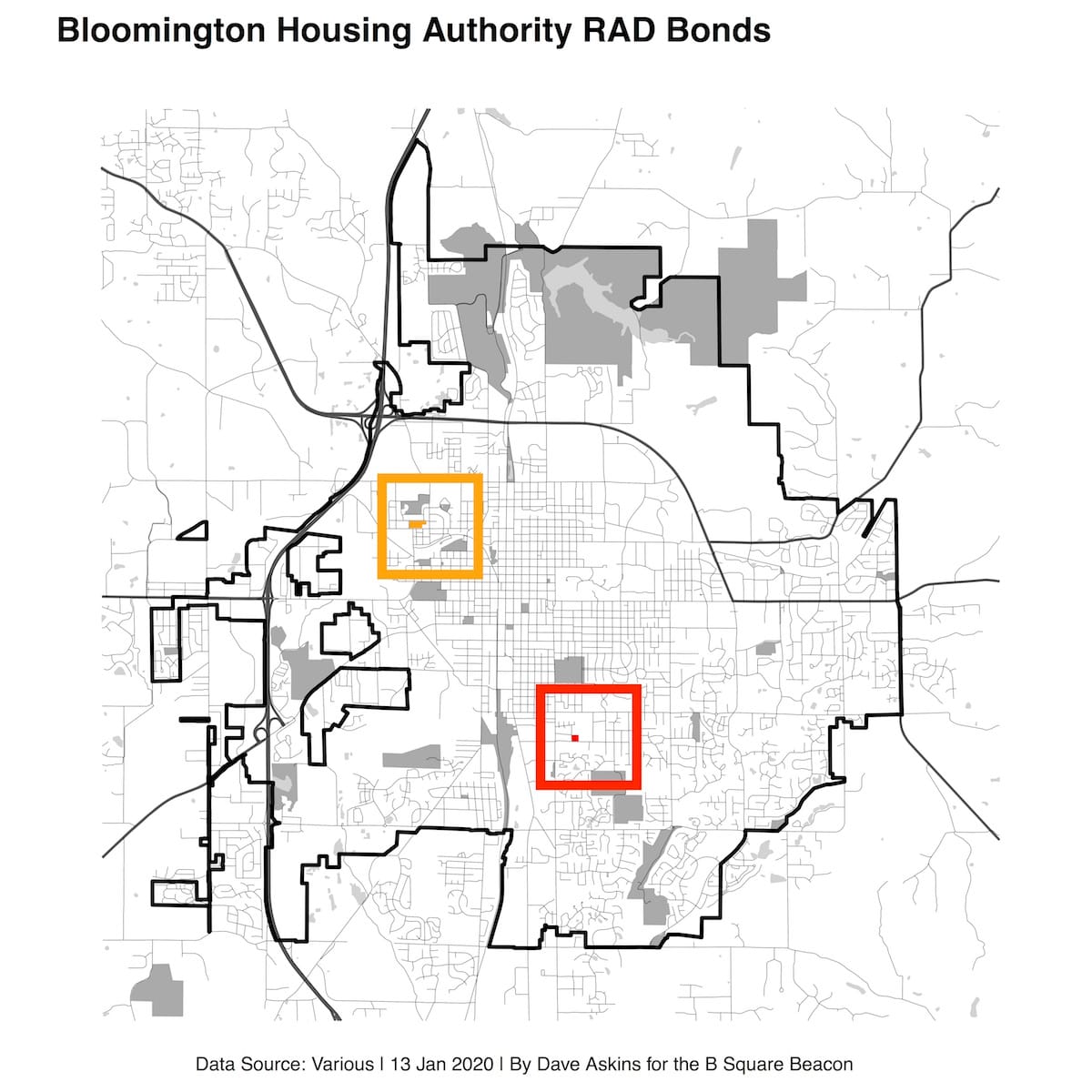

At its regular Wednesday meeting, Bloomington’s city council voted unanimously to approve the issuance of up to $11 million in economic development notes to support the renovation of Bloomington’s public housing stock.

The bond issuance approved this week was for rehabbing two of the three Bloomington Housing Authority (BHA) properties—the Walnut Woods and Reverend Butler sites. BHA’s executive director, Amber Skoby, told the council that planning will start this summer for similar work on the third BHA site—the Crestmont Community.

“After that’s done, we won’t have any more public housing in Bloomington,” Skoby said.

Councilmember Steve Volan’s reaction conveyed amazement: “Does that mean you won’t have a job? I don’t understand.”

Skoby clarified her statement by reviewing the structure of the financing mechanism—which is paying for the renovations in about two years time, instead of the quarter century it would take, using conventional Housing and Urban Development (HUD) public housing funds.

BHA’s properties are being converted to ownership through a private-public partnership under HUD’s Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program. HUD will still be connected to the housing project—through Section 8 vouchers. Current residents of BHA housing will receive special project-based Section 8 vouchers.

Tenants will write their rent check to Bloomington RAD I LP, the new ownership structure. So, who’s going take care of the public housing properties and protect the interests of residents?

Part of the answer is: BHA will still have an ownership stake in the properties. BHA will continue to own the land. It’s one of the controls that BHA’s governing board put in place to ensure that the private-public partnership continues to serve the housing needs of lower-income residents, Skoby told The Square Beacon.

And while the units will be partially owned by a tax credit investor for 15 years, the improvements will be owned by a 501(c)(3) non-profit, called Summit Hill Development Corporation, which was created by the BHA. It is wholly owned and controlled by BHA.

The city council’s meeting information packet describes the work as “addressing current code requirements, environmental remediation, handicap accessibility, structural repair, unit modernization, improvements in energy efficiency, street appeal and site work.”

The work will also make units wheelchair accessible. Added to units will be new hardwired smoke detectors, new flooring, kitchen cabinets, countertops, dishwashers, washers, dryers, high efficiency furnaces and air conditioners. All that work will cost around $53,000 per unit.

The renovations will be done by shuffling tenants in stages to onsite vacant units, Skoby said. It’s important to keep kids in their same school district, she said. Around fall of 2019, HUD allowed BHA to stop leasing units if they became vacant—so Skoby thinks there will be around 25-percent vacancy by the time construction starts in March or April.

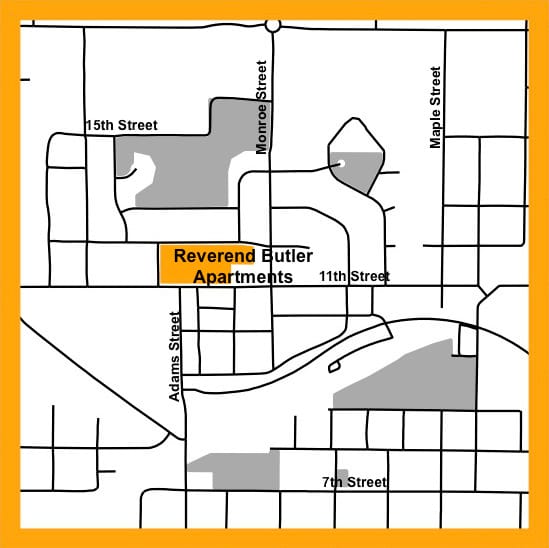

The 56 Reverend Butler units were built in 1972. The 60 units in Walnut Woods were built in 1981.

Part of Skoby’s response to Volan’s question about her future job included the fact that BHA staff will continue to do maintenance for the properties and act as the property manager. So from a resident’s point of view, the only difference will be that a portion of their rent is subsidized through the voucher program.

Responding to a question from councilmember Matt Flaherty, Skoby said that utilities will continue to be included in the rent, when BHA is converted to the RAD project-based vouchers. The predictability of the utility payment through the year is something residents value, Skoby said. And because BHA is paying the utility bill, there’s an incentive for BHA to make the units energy efficient, she said.

The Square Beacon asked Skoby if solarizing BHA properties could be part of the mix for use of a portion of the proposed local income tax (LIT) increase pitched by Bloomington’s mayor, John Hamilton, on New Year’s Day. Skoby said she has not yet been a part of those conversations. But she attended the New Year’s Day swearing-in ceremony, and looks forward to being part of those conversations in the future. “I have lots of ideas. Decreasing utility costs through solar panels would be fantastic,” Skoby said.

Under the RAD program, a family will still pay 30 percent of their adjusted monthly income in rent, as they do in public housing. Under the RAD approach, the difference between the amount paid by the tenant is made up from the voucher program.

After living in a RAD unit with a project-based voucher for one year, tenants will be able to sign up for a regular voucher they can use elsewhere, if they want to, Skoby said. The waitlist for regular vouchers is now around 800 families, but at one point it was over 1,000, she said.

That means BHA’s formerly public housing tenants could be affected by HUD’s calculations for fair market rent.

The fair market rent is calculated each year by the data division of HUD, Skoby told The Square Beacon. BHA then sets its payment standards between 90 and 110 percent of fair market rent. The payment standard is the maximum rent and utilities that BHA will fund for each voucher family.

Skoby said BHA’s one-bedroom payment standard is $725. So a family has to find a unit where rent and utilities are less than $725, and a landlord who will accept Section 8 vouchers. The $725 is 98.5 percent of the fair market rent calculated by HUD for Bloomington in 2019, which was $726. It’s a delicate balance to calculate how to spread 8.5 to 9 million of housing assistance dollars across 1,300 voucher families, Skoby said.

There’s a wrinkle in the fair market rent calculations that HUD did for 2020. From 2019 to 2020, fair market rent for Bloomington dropped. For a one-bedroom unit, fair market rent dropped from $736 to $689, a 6-percent decrease. “It was very surprising,” Skoby said.

HUD’s website indicates the 2020 fair market rents for Bloomington are on hold:

NOTE: The FY2019 FMRs remain in effect for Bloomington, IN HUD Metro FMR Area as a result of a valid request for re-evaluation of FY2020 FMRs.

So the 2020 fair market rents are on hold for a little while.

Did BHA make the “valid request” for re-evaluation? “We did,” Skoby told The Square Beacon. But BHA discovered it would cost around $100,000 for a private consultant to do that review. “We don’t have the funding for that,” she said.

So the hold on Bloomington’s 2020 fair market rents is expiring in a week or so, Skoby said. BHA is going to stick to its same payment standards, Skoby said.

Photos: Reverend Butler Community

Comments ()