City council 2020 budget talks look towards ending leaf collection, increasing trash data

The city’s director of public works, Adam Wason, stood at the podium for three hours at Thursday’s 2020 departmental budget hearings held by the Bloomington city council.

He had to present budget proposals for seven different divisions in his department: admin ($1,918,580), animal care and control ($1,903,971), fleet ($3,358,141), street and traffic ($8,331,136), sanitation ($4,360,802), main facilities ($1,192,487) and parking facilities ($2,397,734).

The seven divisions together made for a 2020 public works budget that totals about $23.5 million. It’s an amount that’s more than any other city department, except for utilities, which is proposed at $46.6 million. In contrast to public works, which is supported by general fund money, utilities gets its funding from rate payers.

Even if it’s safe for the 2020 budget, funding for one public works activity—with a total cost pegged at about $936,000—could disappear in 2021: curbside leaf collection. Councilmembers floated the idea of eliminating it next year or at least reducing its scale by promoting composting.

Responding to the council, Wason indicated his support for cutting the program. And deputy mayor Mick Renneisen told the council, “The administration is receptive to a change in the leafing program…”

Renneisen also indicated support for a long-term plan to consolidate public works divisions all under one roof. He said it’s on a timeline that’s far enough away that it doesn’t appear in any of the city’s current long-range capital plans.

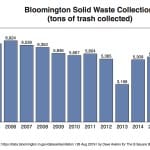

While councilmembers, including Steve Volan, generally reacted positively to the presentations Wason gave, Volan was critical of the lack of data provided for one of the divisions: sanitation. Volan wanted some basic data to appear on a slide about trash collection, like the 6,771 tons collected in 2018—which was about 20 percent more than the 5,683 tons the year before.

Leaf Collection: “Our villages will rise up!”

Currently, for a seven-week period from November to December, the city sucks up the windrows of leaves that residents rake up next to the curb for 234 miles worth of streets. A webpage dedicated to the leaf collection program includes a link to a dynamic map that’s meant to keep residents up to date on the status of the city’s leaf pickup efforts.

Councilmember Dave Rollo led off the commentary in favor of reducing the leaf collection program: “I guess what I’m getting at, if we had a concerted program to educate people to compost leaves, instead of raking them to the curb, maybe we can cut that budget by half and that’s hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Public works director Adam Wason told Rollo: “We will have a lot of residents very upset if we stop our leafing program.” And Rollo replied that he was not suggesting that the program be eliminated. “I’m suggesting through an educational effort that we cut it by 5 percent per year and maybe get it down to half the number and save $400,000,” Rollo said.

Wason said he would “gladly” continue to explore the educational efforts. Wason added a stronger sentiment: “On the verge of making some members of the public a little angry with me, I would cut it tomorrow if I could.”

As reasons for eliminating loose leaf collection, Wason echoed the environmental impacts that Rollo cited and how composting would be a better approach. To those reasons, Wason added: “[Leaf collection] is probably the service that we provide the lowest level of customer satisfaction. By that I mean, we can never control when the leaves fall, we can never control when the first snow comes, and we can never make the entire community happy. Because if you start in their neighborhood they’re gonna think we’re never coming back.”

As one example of a complaint about leaf collection, the following message was recorded in the city’s uReport system on Dec. 20 last year:

Leaf Collection

… I am really sorry and disappointed by your policy practice. You send a notice about 2 month ago and announced you would collect continuously. But you did just one time. Look around several places here. The street is dirty full of leaves. It is decaying. Please clean up as soon as possible. If you don’t our villages will rise up!!!!!!!!!!

The number of complaints his department gets about leafing, Wason wagered, outpaces potholes and snow combined. Later in the meeting, councilmember Steve Volan called the number of leaf complaints described by Wason “head turning.” Rollo’s compost education idea should be a high priority, Volan said.

Councilmember Isabel Piedmont-Smith’s statements on the topic of leafing went further than educational steps:

I think we definitely need to get rid of the leafing program. It’s just not sustainable. We spend $900,000 on this program where people could, given the right knowledge and tools, take care of the leaves on their own property and compost them and have good compost to use in their gardens. It defies logic that we still do this. So I think this is the last year that we should do it.

Piedmont-Smith added to the criticism of the leaf collection program, by pointing to complaints heard through the solid waste district about the product that is delivered by the city. Because the equipment that sucks up the leaves also sucks up “everything in its path” the product from the city has brooms, rakes and trash of all kinds, Piedmont-Smith said.

“I will be supporting this budget,” Piedmont-Smith said, “but if those leaves are in there next year, they’re not gonna get my approval!”

Deputy mayor Mick Renneisen was in council chambers Thursday night, but occasionally stepped out, which Wason used to humorful effect—the joke being that he was speaking franking about leaf collection only because Renneisen was out of the room.

At the end of the presentation, Reinneisen clarified that the administration’s position and Wason’s are aligned: “The administration is receptive to a change in the leafing program. We do support the study and possible elimination of the way we are doing it today. Just want you to know that we are not opposed to that at all.”

Trash Data: “We’re not afraid to publish data.”

The city recently switched from a sticker program for trash collection to one where residents pay for carts that can be emptied by a truck equipped with an automatic arm.

In his presentation, public works director Adam Wason said there’d been an increase in the number of people using the new cart-based program. He also said that the software vendor the city had used for tracking the use of carts didn’t perform up to expectations and the city had switched vendors. That meant the finer-grained data on cart usage was not available.

Councilmember Steve Volan asked how Wason concluded there’d been an increase in usage of the carts, if there was no data available. Wason indicated that the conclusion about an increase in cart usage was based on the total tonnage of solid waste collected.

Volan wanted to know why the increase in tonnage wasn’t included in the presentation. During the back and forth between Volan and Wason, Volan pulled the sanitation dataset from the city’s website. “I just literally pulled up the sanitation data set,” Volan said, “but one thing I’m surprised by, in a budget that is otherwise rife with details of percentages going up and numbers in other departments, the most basic stat of how many tons of trash picked up wasn’t present in the slide. You didn’t mention it. Why?”

Wason said it was a matter of trying to present a lot of information as efficiently as possible. “I wish sanitation would not be afraid of publishing data,” especially when the data showed that a program was going well, Volan said.

Wason responded by saying, “The word ‘afraid’ is strong. We’re not afraid to publish data.”

Here’s what the trash collection data looks like, when it’s plotted out.

What happened in 2013?

Rhea Carter, Bloomington’s director of sanitation, told The Beacon in an email from early in 2019 that the drop in 2013 was probably due to particularly strong local waste diversion efforts that year.

“The ‘Hoosier to Hoosier’ resale effort that year likely had a noticeable impact since that was around the time period it first became a high profile event on both the Indiana University campus and throughout the community,” Carter said. That year there were also several free electronic collection events sponsored by local and national companies or other organizations, she said.

Comments ()