Column: Bloomington city council quarrel about committees could be helped by a look back to 1954

On Wednesday this week, Bloomington’s city council will convene a stand-alone committee-of-the-whole meeting to discuss one item—an ordinance that would put an all-way stop at the intersection of Maxwell Lane and Sheridan Drive.

This week’s committee meeting has been listed on the council’s 2022 annual calendar since the council adopted the schedule late last year.

But at last week’s council meeting, after the stop sign ordinance was introduced and given a first reading, a motion was made to skip the committee meeting. That motion failed on a 4–5 vote “along party lines.”

The bit inside scare quotes is a joke, because all nine members of Bloomington’s city council are Democrats. But on the question of legislative process, the council has been sharply divided—along pretty much the same lines—since the start of 2020, when the current edition of the city council was sworn into office.

A point of consensus among councilmembers seems to be the value of a legislative process that gives councilmembers a chance to dig into legislation on at least two separate occasions in front of the watching public.

Under Bloomington’s local code, any ordinance has to receive two readings before it can be enacted. That’s consistent with state law, which does not talk about readings per se, but does prohibit the enactment of an ordinance on the same day or at the same meeting when an ordinance is introduced—unless there’s unanimous consent.

The council’s predominant pattern is to take a vote on the enactment of an ordinance at its second reading.

But a piece of current local code that has to be figured into the mix is a prohibition against the discussion of any ordinance at its first reading.

That prohibition means that the council has to engineer a different first chance for public discussion, at some point between the first and second readings. Whatever meeting format is chosen, the timing for the first public discussion has to come after the meeting when an ordinance is given a first reading, but before the meeting when the ordinance is given a second reading and voted on by the council.

In 2020, the councilmembers who advocated for creation of four-member standing committees saw those standing committee meetings—in the week between first and second readings—as a good format for the public’s first chance to see councilmembers deliberate on legislation.

Before 2020, it had been the custom for the council’s committee of the whole to discuss legislation between the first and second readings of an ordinance. After trying out standing committees in 2020, a majority of councilmembers in 2021 supported reverting to the committee of the whole as the format for the first public discussion.

At last Wednesday’s first reading of the stop sign ordinance, the council spent 15 minutes debating the question of skipping this week’s committee-of-the-whole meeting, before a majority decided to leave the committee meeting on the calendar.

That 15 minutes could have been spent deliberating on the merits of the stop sign ordinance—except for the piece of local code that prohibits any discussion at first reading.

Even though Bloomington’s local code about meeting procedures in many ways mirrors requirements in state law, I can’t find in state law any prohibition against discussion of an ordinance at first reading.

What useful purpose is served by the prohibition against discussion at first reading?

I don’t think there is one—at least not in 2022. But maybe there was a useful purpose 68 years ago.

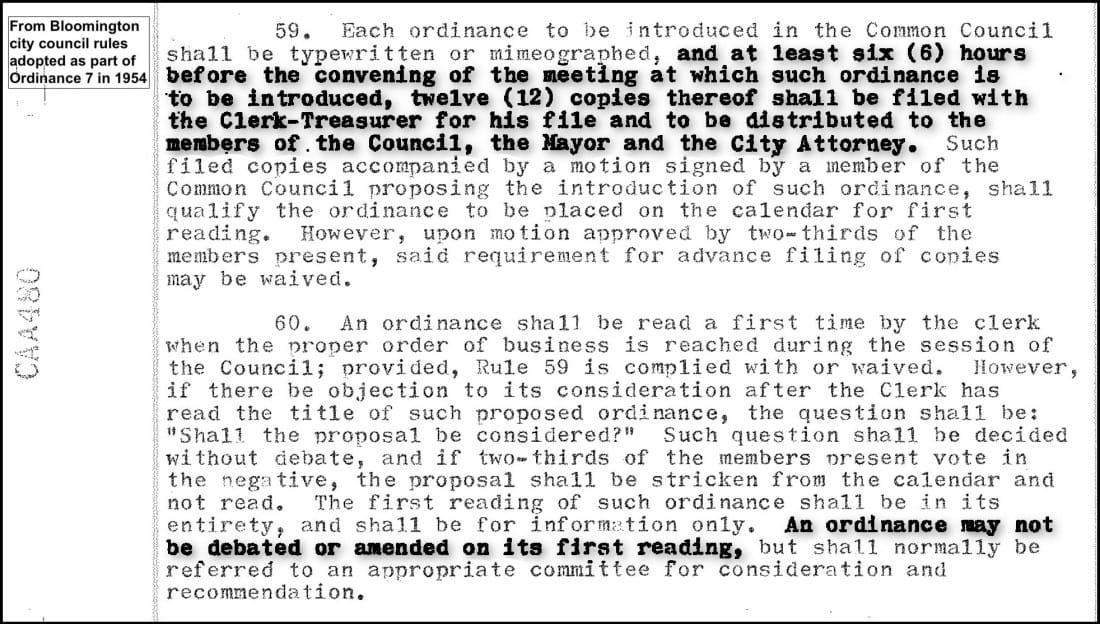

When the council adopted Ordinance 7 on May 4, 1954—which governs meeting procedures—it included the prohibition against discussion or amendment of an ordinance at its first reading.

In the full context of that 1954 ordinance, I think prohibiting discussion or amendment of an ordinance at first reading probably did serve a useful purpose. The prohibition against discussion at first reading appears to have been a kind of tradeoff, in connection with allowing very late addition of items to the agenda.

Ordinance 7 allowed a councilmember to add an ordinance to meeting agenda, just six hours before the meeting. Some assurance that literally nothing could happen at a first reading—no discussion and no amendment—might have given the public some measure of comfort.

That comfort would have come from knowing there would be some time to review the ordinance, before any public debate by the council took place. That would make it possible to follow the lines of argument when the council eventually did discuss the ordinance.

Over the next 68 years, many of the requirements in Ordinance 7 have been modified. It’s no longer possible to add an ordinance to an agenda six hours before the start of a meeting. Under current city code, the material related to an ordinance has to be submitted to the city council office at least 10 days before the meeting when it is given a first reading.

But the prohibition against discussion at first reading remains.

Given the changes to city code, about the deadline for submitting material to the council office, the public could have access to all of that information a full 10 days before an ordinance is given a first reading.

Surely 10 days is a long enough time for councilmembers and the rest of the public to be ready for a public discussion of an ordinance at its first reading.

That’s why the council should at least consider amending city code, to allow for discussion and amendment of an ordinance at its first reading.

That approach would build into the standard legislative pattern at least two chances for councilmembers to deliberate in public on every ordinance—once at its first reading a second time at its second reading.

The question of what kind of committee should hear legislation between first and second readings would be rendered moot—one less point of friction between councilmembers.

Sometime in the next few weeks would be a perfect time for the city council to take up this issue—just in time for consideration of its annual calendar for 2023.

Comments ()