Column: Bloomington’s city council should increase Jack Hopkins social services budget for 2021

The headline to this column could provoke a reflexive response from longtime Bloomington city councilmembers. As a matter of law, they’ll say, it’s not up to them, but rather the mayor to increase the budget for Jack Hopkins social services.

From a legal point of view, I think they might be wrong.

But all nine city councilmembers and the mayor are members of the Democratic Party. So even if they’re right on the legal question, partisanship works in their favor.

Without confronting any of the typical partisan barriers that some cities might face, Bloomington’s elected officials could fund more social services.

At least a 10-percent increase in Jack Hopkins social services funding is achievable for the 2021 budget, even assuming no additional revenue.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there’s no question that the need for social services has increased this year, and likely will in future years.

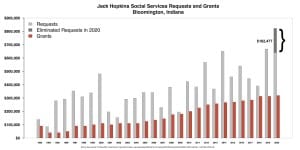

This year, the amount of Jack Hopkins requests was $822,971, easily setting an all-time high since 1993, when the fund was established. That’s more than two-and-a-half times the $311,000 in this year’s Jack Hopkins budget.

This elevated need outpaces the incremental budget increases that the Jack Hopkins social services fund has seen in recent years. Last year’s bump was 2 percent, from $305,00 to $311,000.

How could we provide at least a 10-percent increase in 2021?

Let’s assume the 2021 budget would have included a 2-percent increase anyway—that’s $6,220. From each councilmember’s $2,180 salary increase last year, let them keep $180 and take $2,000—for an extra $18,000 in Jack Hopkins social services funding.

From the mayor’s $7,050 increase last year, let him keep $170 and take $6,880 to put towards extra Jack Hopkins funding.

To sum up, that’s $18,000 + $6,880 + $6,220 = $31,100. Exactly 10 percent of last year’s Jack Hopkins budget.

Why are the salaries of Bloomington’s elected officials a natural place to look to pay for social services? Because that’s in part how the Jack Hopkins social services fund was started, back in 1993.

According to Herald-Times reporting from that era, the total amount available in 1993 was just $90,000. And of that amount, $6,363 came from raises that the city council decided to turn down.

If this year’s city council drew on their own salaries to increase social services funding, they would be tipping their historical hat to the city council of 1993.

If the city council can’t smooth out any same-party friction between itself and the mayor to get what it wants in the 2021 budget, it might be worth revisiting the legal question.

A common belief among longtime councilmembers is that they’re powerless to amend the administration’s proposed budget, except downward. They don’t think they have the ability to increase any part of the budget, unless the mayor agrees.

That’s a belief likely based on a state statute that says they cannot increase some items.

From the state code IC 36-4-7-7 (emphasis added in bold italics):

Report of estimates; ordinance fixing taxation rate; appropriation

Sec. 7. (a) The fiscal officer shall present the report of budget estimates to the city legislative body under IC 6-1.1-17. After reviewing the report, the legislative body shall prepare an ordinance fixing the rate of taxation for the ensuing budget year and an ordinance making appropriations for the estimated department budgets and other city purposes during the ensuing budget year. The legislative body, in the appropriation ordinance, may reduce any estimated item from the figure submitted in the report of the fiscal officer, but it may increase an item only if the executive recommends an increase. The legislative body shall promptly act on the appropriation ordinance.

I think there’s at least some room to question whether the statute ties the hands of city councilmembers in the way they believe it does.

The citation to IC 6-1.1-17 in the quoted section is significant, I think, because it makes clear that “the report of budget estimates” is a report about revenue estimates. That suggests that the items that a city council is prohibited from increasing could reasonably be interpreted as revenue estimate items, not planned expenditure items.

In any case, if I were sitting on the city council I would sure want a public, written legal opinion laying out exactly how much latitude a city council in the state of Indiana has when considering amendments to a city administration’s proposed budget.

I would want specific examples showing which amounts can and cannot be increased or decreased, with a detailed explanation why or why not. I would want a template I could use to draft proposed amendments to the budget.

The question is: Can the Bloomington city council, on its own authority, increase Jack Hopkins funding, making up the difference by dipping into the salary lines of elected officials?

What if the answer to that question turns out to be no?

To put city budget planning in a little bit of context, August is when the city council holds its hearings on the draft budget. At the end of September is when the administration presents the final version to the council. In early October, the budget gets adopted.

So I think city council members should use their “report” time at every regular meeting between now and the hearings in August to report to the public about their 2021 budget efforts.

Specifically, they should use their city council meeting time to report what work they’ve done since the last council meeting to encourage the mayor to increase Jack Hopkins funding by 10 percent or more in his 2021 proposed budget.

Comments ()