Column: How do you get food justice (or anything) on the Bloomington city council’s agenda?

Bloomington city councilmember Isak Asare spent part of his Saturday talking about food justice—the idea that everyone deserves access to nutritious and affordable food.

Asare was not the only one.

He was one of five people who participated in a panel discussion hosted by the People’s Market, and moderated by Jada Bee, a market co-founder. Other panelists included three Black farmers, Lauren McCalister, Ty Simmons and Ephraim Smiley. Simmons and Smiley had made the trip down from Fort Wayne to participate. McCalister’s journey from Ellettsville was shorter—she’s the LFPA (Local Food Purchasing Assistance Program) executive director at People’s Market.

Rounding out the group were Asare and Monroe County councilor Jennifer Crossley.

Asare talked about the nine-member city council on which he started serving this year. “Nine of the nine people on city council will be like: Yeah! We need food justice!” Asare said.

He added, “But we will not talk about that anytime soon.”

Why not?

Asare’s answer: “Because, we—hear me very clearly—we, as a body, can’t figure out how to get it on our agenda!”

A couple of times already, during council meetings in the first six weeks he has been serving, Asare has raised the issue of agenda setting and meeting structure. It’s actually encouraging that he brought it up again on Saturday.

It’s also encouraging that on the topic of access to local food, Asare should have at least one willing collaborator on the council. With more than two decades of service, representing council District 4, is Dave Rollo. Reached by phone late Saturday, Rollo said that he and Asare had met early on, to talk about their areas of agreement, and local food was one of those areas. That’s great to hear.

Anyhow, it means I am now looking to Asare and Rollo to figure out how to get food justice onto the Bloomington city council’s work plan.

On Saturday, Asare gave a recent example of the way Bloomington’s city council agenda currently gets set, and followed—to the detriment of more important topics.

Appearing on the agenda for the city council’s first February meeting was an ordinance that amounted to a clean-up of wording. In several places, the ordinance replaced in city code the phrase “transportation and traffic engineer” with “city engineer.” Any reference to “his or her” was replaced with “their.” The ordinance also added some standards for protection of trees in the public right-of-way.

Glossing over the procedural requirements of state law and local code, at the Feb. 7 city council meeting, Asare made a procedural gambit to take care of that ordinance in a single step, by voting on it that same night. But it was clear that Asare’s effort would not have had the required unanimous support, so he did not push forward on it.

That meant the council held its Feb. 14 meeting the following week as scheduled, with just one piece of legislative business on its agenda—the wording cleanup ordinance. (It passed unanimously!)

About that particular ordinance, Asare said on Saturday, “I’m thinking, we could vote on this next month, we could vote on this next year, or we could vote on it now. This is an inconsequential conversation, right? But it’s filling up all of our space.”

Asare continued, “We need a government that is actually responsive to the needs of the people.

That’s not rocket science.” A barrier to being responsive to the needs of the people, Asare said, is the way the council’s meetings are designed and the agendas get set.

Asare put it like this: “Enemy Number One are processes—and let me be clear, these are processes that are rooted in white supremacy—that keep order.”

He continued, “When you make a process that is based on order, the idea of that process is to keep some people out, is to decide: What do we talk about? When do we talk about it? How long do we talk about it?” And it makes who gets to talk about it most important.”

Those processes “make it so difficult to move the agenda towards actionable items of immediate importance,” Asare said.

“Why don’t we create an ordinance that says that every tree planted in the next five years in Bloomington needs to be fruit- or nut-bearing?” Asare asked.

Asare identified part of the problem as a need to get such an ordinance onto the city council’s agenda. “The only way for us to get it on the agenda is that somebody would have to introduce it—as a bill.”

Asare ticked through a list of competing time commitments that would make it challenging for him alone to write up a draft ordinance. “I can’t defy the laws of physics,” he said. For one thing, Asare has a full-time job as assistant dean for undergraduate affairs at the Hamilton Lugar School of Indiana University, and two children.

Asare continued, saying, “But there’s a better way forward. And we can actually do consensus-building activities in the city government, where we can all come to the table and say: Here’s some things that we want to do. And then we can say: Hey, Jada Bee, write the draft and bring it to us!”

Jada Bee, who is one of the co-founders of People’s Market, would be a natural person to ask to help draft an ordinance. Among her offerings as a vendor over the last few years have been applesauce and persimmon pulp—from wild-foraged fruit. In any conversation about the topic, it will not be long before Jada Bee will bring up the idea of planting nut- and fruit-bearing trees on public land.

I don’t think the Bloomington city council necessarily needs to enact an ordinance to compel the planting of nut- and fruit-bearing trees on public land, even if more such trees is the goal.

Still, it makes sense for the city council to push the topic of food justice forward—a public conversation among its members, new Bloomington mayor Kerry Thomson’s administration, and residents. It makes sense because the city council is the fiscal body for the city. So the city council at some level has something to say about what kinds of trees the city purchases for planting on city-owned land.

Local food is a topic that I have on occasion heard councilmember Dave Rollo bring up over the last five years. But it has mostly been in the form of one-off mentions, not an organized approach to adopting policies that might result in easier access to fresh food for local Bloomington residents.

Reached by phone late Saturday, Rollo was receptive to the idea of choosing trees for planting on public land that are nut- and fruit-bearing. In fact, he told me that “edible landscapes” were a concept that had been included in the 2009 report from Bloomington’s peak oil task force, which he led. That report concludes:

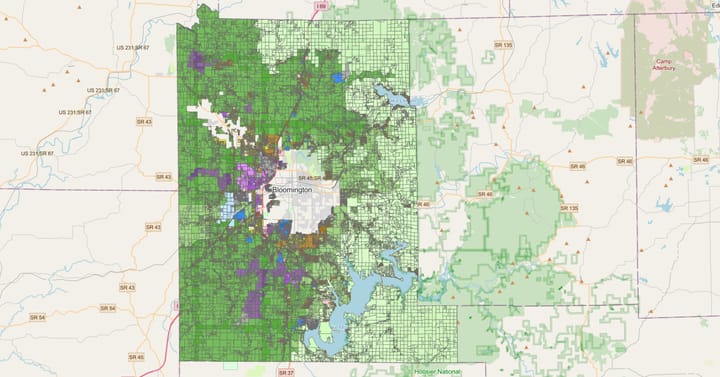

[A]rable land available within the City of Bloomington alone (as much as 8,000 acres, or upwards of 5,000 square feet per resident) is potentially sufficient to meet most of the vegetable, fruit, egg, and some poultry requirements of city residents were it to be cultivated to the maximum extent possible using the most productive and intensive garden‐scale methods.

At the time, Rollo told me, there had been pushback to the idea of planting fruit-trees on public land—from the city’s urban forester at the time. Rollo said the objection had been: “They’re messy. Who’s gonna clean up the mess?”

Rollo allowed that the “mess” was a non-trivial consideration. Fruit could fall on sidewalks, make it slippery, attract hornets, start to smell bad were among the parade of horribles that could come with planting fruit-bearing trees.

But Rollo said that what he had suggested at the time was: Why don’t we at least do a pilot? Rollo suggested trying some place where people want the trees—some neighborhood where they’ll say, “I can’t wait to harvest the apples, the pears, the pawpaws, or persimmons.”

Rollo said, “It just went nowhere.”

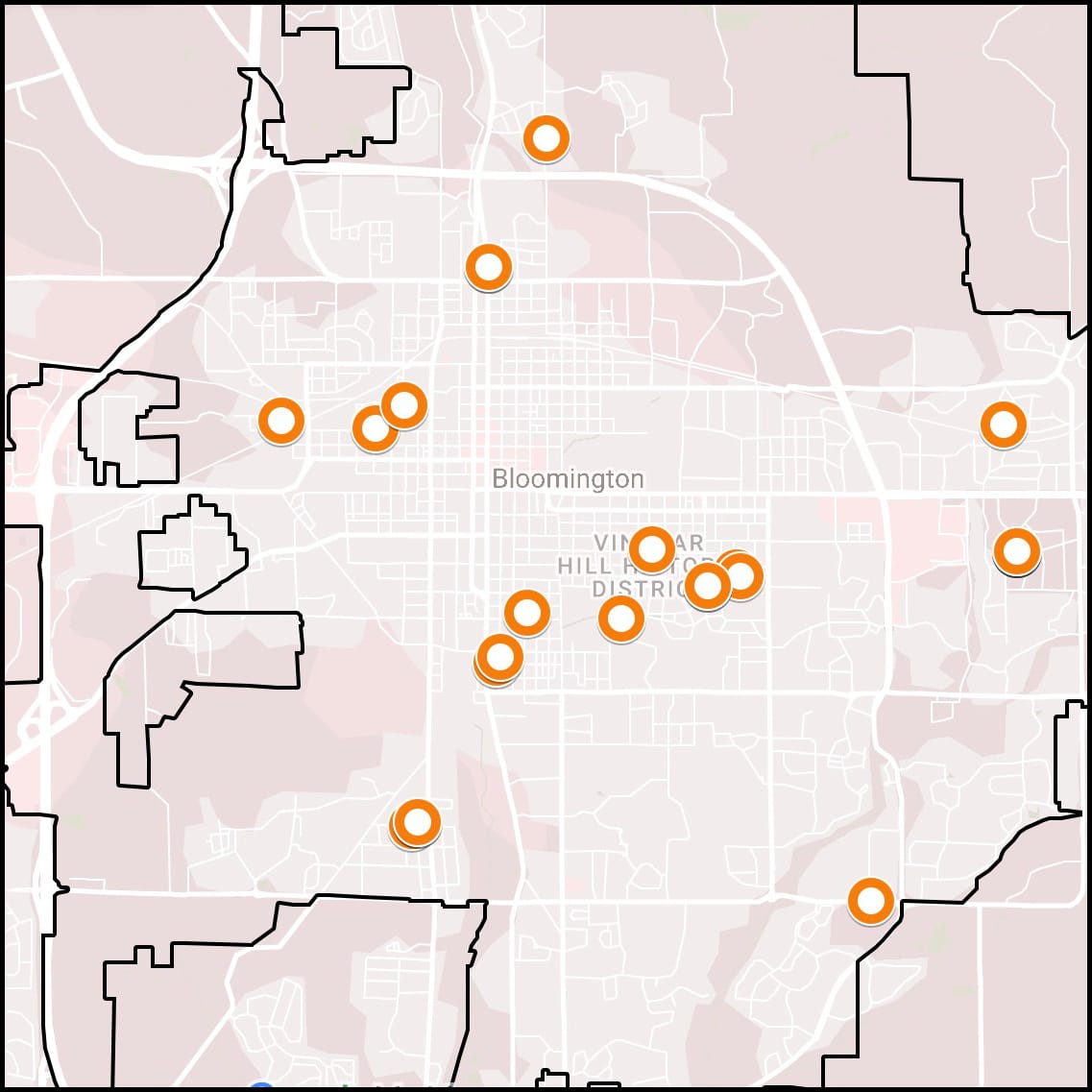

There are already some fruit-bearing trees planted in Bloomington’s public right-of-way. For example, the city’s tree inventory shows 25 persimmon trees sprinkled across the city. Bloomington’s persimmon trees are plotted out as orange dots on the city map, which is included as a graphic with this column.

Various one-off suggestions that I have heard city councilmembers make over the last five years typically come in the context of the annual budget deliberations, which take place at the end of August.

But the administration’s basic preparation for the budget, which gets presented to the council in late summer, has surely already started for this year. In August, it will be too late to make suggestions that can easily be incorporated into the 2025 budget.

So it’s not too early right now for Bloomington’s city council to figure out what topics it wants to put on its work plan (aka its “agenda”)—topics about which it might want to express an opinion to the administration.

It’s not necessary to think in terms of an ordinance or a resolution—even if those are the standard tools used by the city council. Let’s imagine a different tool, like a simple motion made by a councilmember—supported by a majority vote of the council, at a collaborative work session attended by the mayor, resident-experts, and the public at large:

I move that the city council hereby requests that the mayor incorporate into the 2025 budget a pilot program for systematically planting nut- and fruit-bearing trees on city-controlled land.

Such motions would be enough to give the mayor some idea about what specific priorities should be reflected in the budget. If the 2025 proposed budget doesn’t include a pilot fruit tree program, after the council has requested it, there would be a chance to ask Bloomington mayor Kerry Thomson: Why isn’t there something in this budget to support a pilot fruit tree program?

Even if Bloomington’s city council is off to a slow start as far as making city government responsive to the people, Asare’s remarks during Saturday’s panel actually left me feeling optimistic.

Asare said on Saturday that he doesn’t think Bloomington’s city council will have food justice on its agenda anytime soon. I am hopeful that Asare’s city council colleagues will prove him wrong.

Comments ()