Election board to meet on question of disqualified signatures for Bloomington mayoral hopeful

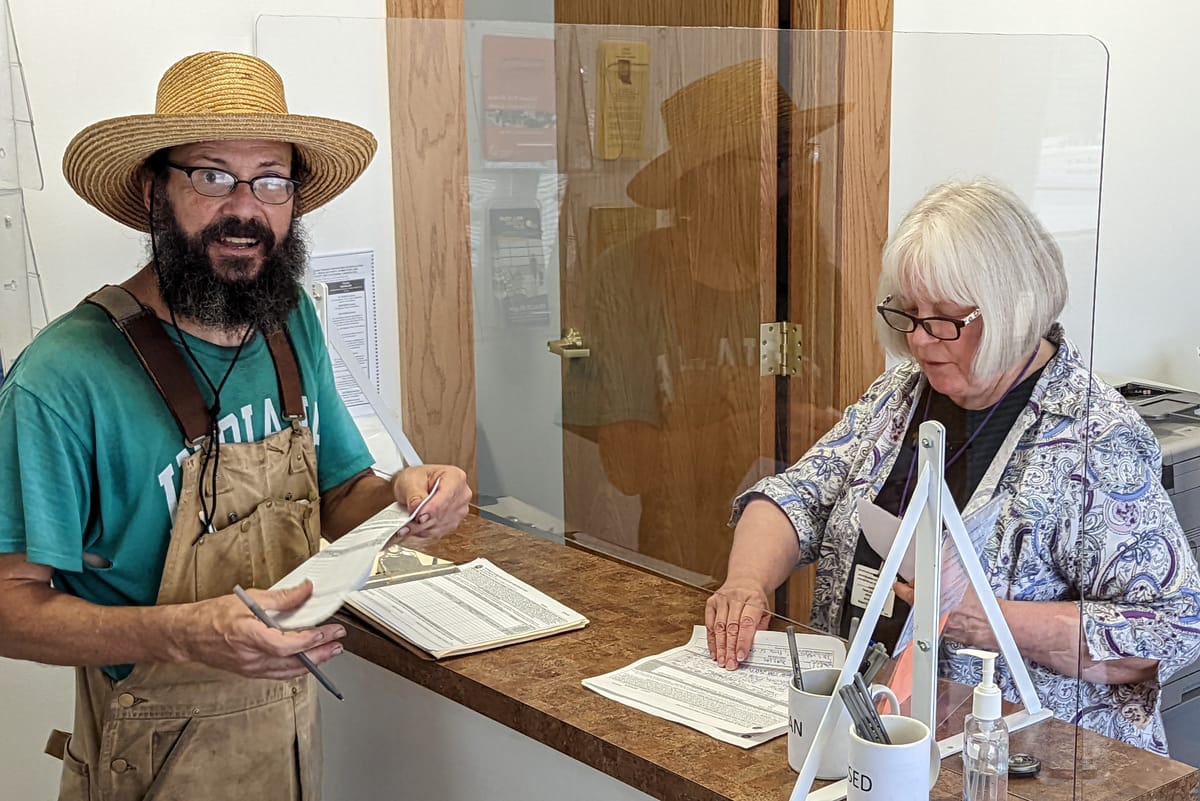

Questions about disqualified petition signatures, which were submitted to county election staff by Bloomington mayoral hopeful Joe Davis, will be the topic of discussion for Monroe County’s election board next Thursday (July 13).

Davis sought to appear on the Nov. 7 city election ballot as an independent candidate. To meet the requirements under state law, he had to submit at least 352 signatures by June 30 at noon. Davis fell 14 signatures short.

He submitted more than 600 signatures.

To challenge the disqualification of some signatures, Davis has filed a CAN-1 form, which can be used by “a candidate seeking to contest the denial of certification due to insufficient signatures.”

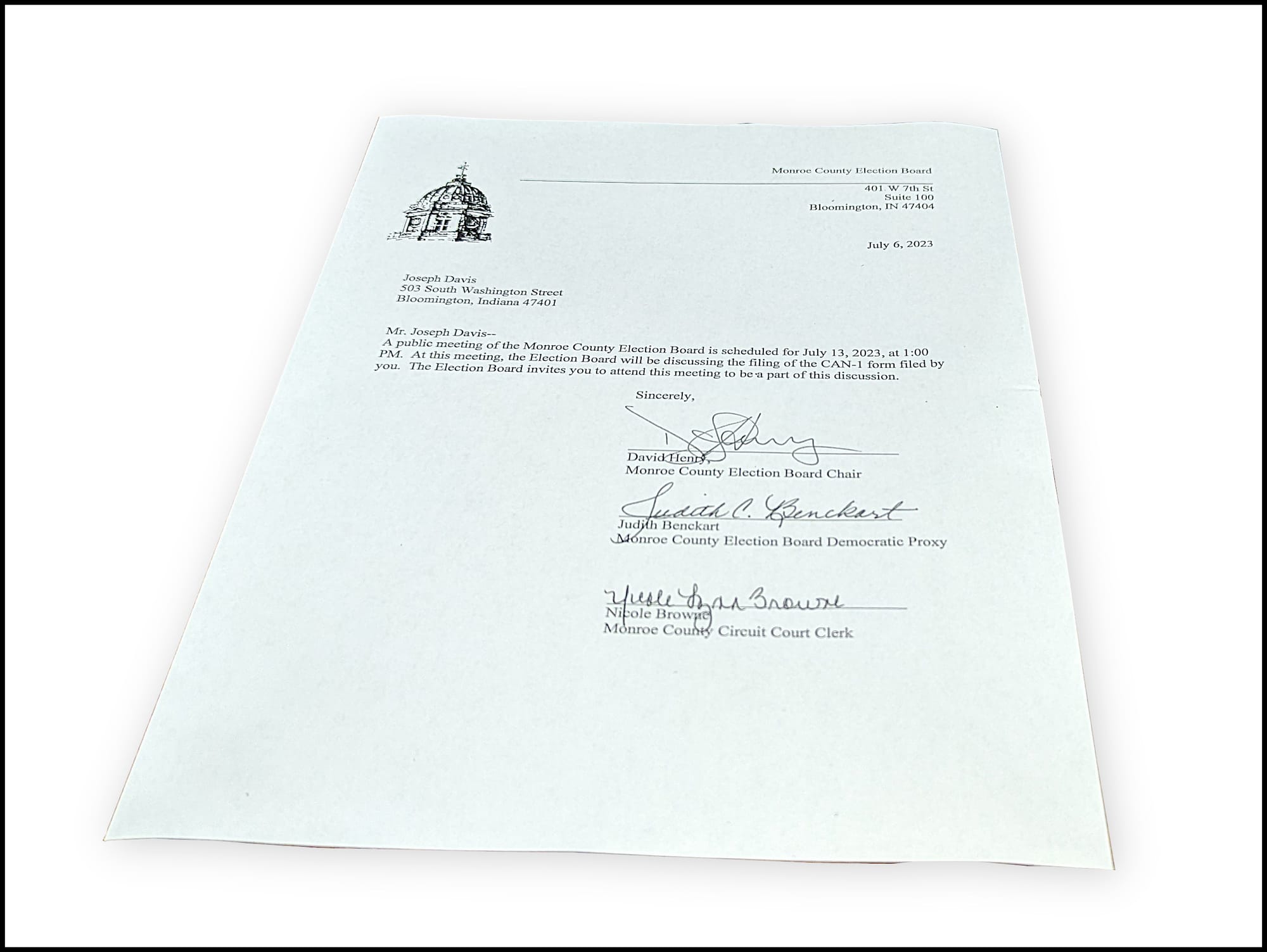

At its meeting this past week, the board gave the challenge by Davis some initial discussion, opting to continue its meeting on July 13 at 1 p.m. The board also decided to send Davis a letter inviting him to attend and be a part of the discussion.

As it currently stands, the race for Bloomington mayor is uncontested. The only candidate who will appear on the ballot is Democratic Party nominee Kerry Thomson. No write-in candidate registered by the July 3 deadline.

The timing of the election board’s next discussion—four days before the deadline for Davis to declare his independent candidacy—would still give Davis enough time to submit his official declaration as a mayoral candidate by July 17.

Based on the preliminary discussion by the board, it does not appear likely that Davis will wind up on the ballot. But the fact that the board is meeting again on the topic means there’s still a chance, even if it is a longshot.

The number of required signatures (352) is not a nice round figure, because the minimum number is defined under state law as 2 percent of the total votes cast in the city of Bloomington in the most recent statewide race for secretary of state.

At last Thursday’s meeting, Monroe County election board member David Henry said that the wording of Davis’s statement on the CAN-1 form refers to “many” signatures that Davis contends were incorrectly disqualified. Based on Davis’s challenge, it’s not possible to know which disqualified signatures he is contesting, Henry said.

Henry is the Monroe County Democratic Party’s appointee to the three-member board.

Signatures on qualifying petitions get disqualified for various reasons. Some people sign a petition, even though they’re not registered to vote at all. Others will sign, but are registered at an address some place other than inside Bloomington city limits.

The category of disqualification that is likely at the center of Davis’s situation are signatures of “pending voters”—people whose registration was still pending and not yet active. Indiana’s voter registration guide says that a voter has to wait seven days after a postcard is mailed to the address where they registered, before they become an active voter.

The seven-day waiting period, during which someone is a “pending voter” is also spelled out in state election law [IC 3-7-33-5]

As a part of Davis’s effort to gather signatures, he helped people fill out voter registration applications, and turned them in, so that they could sign his petition.

Davis turned in petition signatures in several batches, starting in April. He also turned in a handful just a minute before the June 30 noon deadline.

At Thursday’s board meeting, chief deputy county clerk Tressia Martin, deputy clerk for voter registration Larime Wilson, and county attorney Molly Turner-King, laid out the legal ins and outs of how the office staff handled the petition signatures.

They evaluated the signatures as Davis turned them in, based on the status of the person in the system—at the time staff tried to validate them as an active registered voter.

Wilson said that election office staff used a module in the Indiana State voter registration system to attempt to verify the signatures. Staff tried to verify that the people who signed Davis’s petition were registered voters at the address that they wrote on the petition, and that their signature was a reasonable match to any signatures in the system.

The way the election office staff processed the signatures—evaluating the status of the voter at the time—follows state election law. [IC 3-8-6-8] The law says that staff have to certify that “each petitioner is a voter at the residence address listed in the petition at the time the petition is being processed.”

According to Martin, if someone was just a pending voter, they would not have shown up at all in the module of the state’s voter registration system that staff use to verify signatures. Otherwise put, that module of the system does not indicate that the voter has submitted an application that is pending—it just returns no result. That means it’s probably impossible to say how many of Davis’s disqualified signatures were ruled out because of their status as pending voters.

Election board member Judith Benckart, the Republican Party’s appointee, asked how long it would take to go back and check all 600 signatures as if they had all just been turned in. That would mean that voters whose applications were pending at the time the signatures were checked, would likely have become registered voters by now.

Benckart allowed that this approach could also mean disqualifying some signatures that had previously been counted—for example, if the person had died in the time since their signature had been verified.

Martin estimated the time for the staff to re-check all 600 signatures at around three days.

Benckart was weighing a hypothetical scenario where Davis had waited to turn in all the petition signatures on the final day before the deadline, appealing to the idea of “the fairness of it.”

Benckart said she understood that the election board cannot order the staff to re-check the signatures, adding that “it would just simply be a request.”

The lack of any authority for the election board to order the staff now to recheck the signatures, could be based on a part of state law regulating how much power local government has.

The law was cited by Martin at Thursday’s meeting, [IC 36-1-3-8]. It says that a local unit cannot “adopt an ordinance, a resolution, or an order concerning an election described by IC 3-5-1-2, or otherwise conduct an election, except as expressly granted by statute.”

Monroe County clerk Nicole Browne, a Democrat who sits on the board in her role as clerk, indicated she is not in favor of rechecking the signatures. She put it like this: “I feel that is a slippery slope that takes the onus off of the candidate’s duty to collect valid signatures.”

The election board’s Thursday meeting, to continue discussion of Davis’s CAN-1 challenge, is set to start at 1 p.m. in the Nat U. Hill room of the Monroe County courthouse.

Comments ()