Homeless camp removal: Monroe County grants 1-week pause after activists disrupt meeting seeking 4-month delay

Monroe County commissioners delayed the planned Dec. 8 removal of the Thomson encampment by 1 week, after activists urged more time for relocation amid frigid weather. The move followed a tense meeting featuring sharp criticism and a brief recess. Notices were issued Dec. 1 to 40–50 residents.

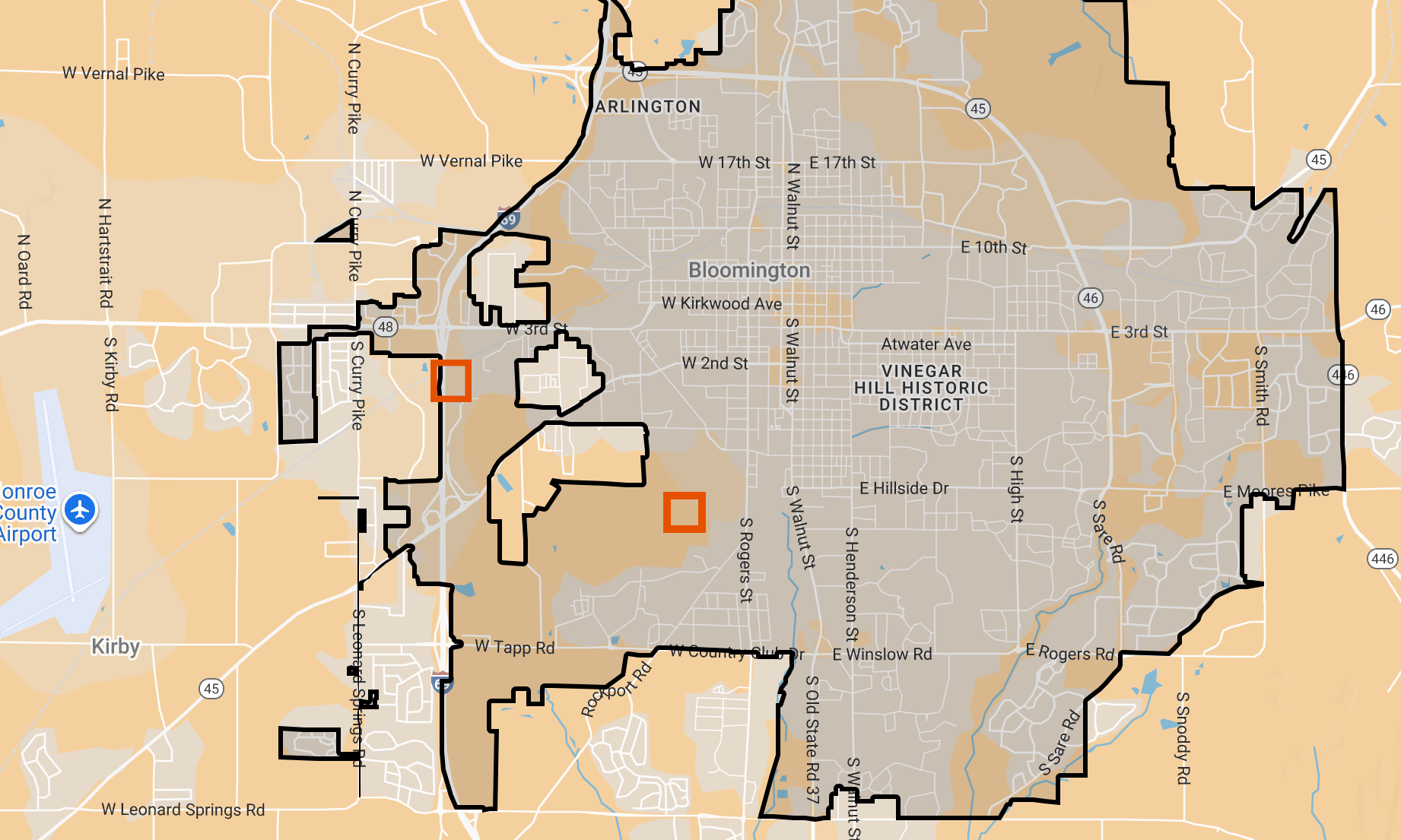

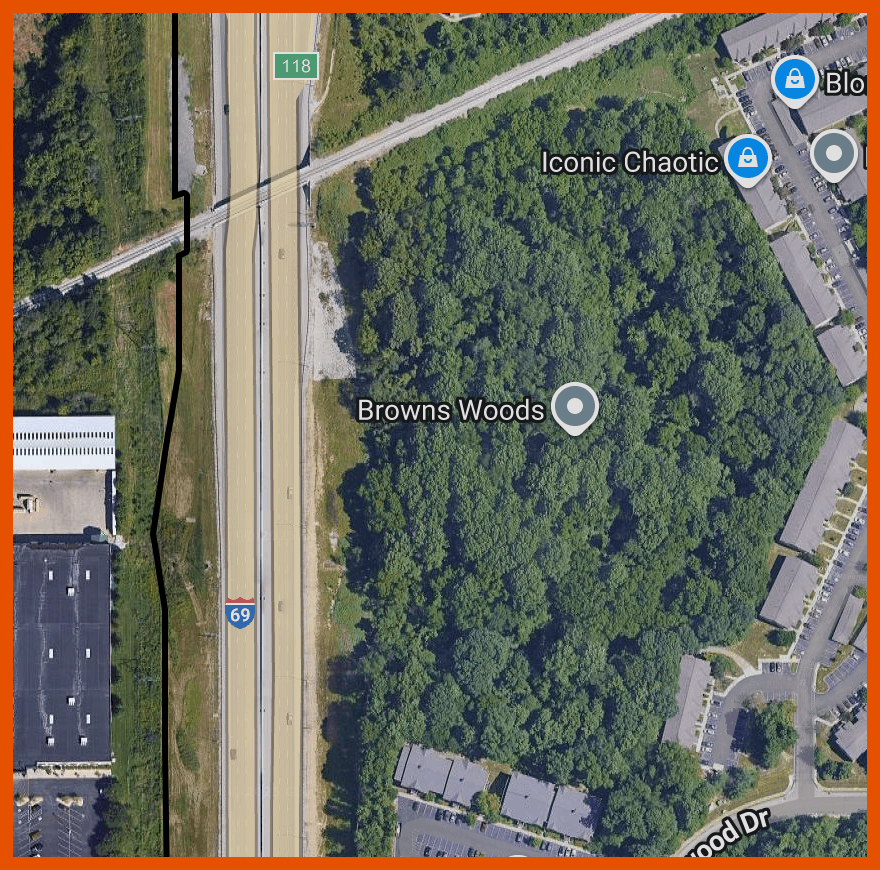

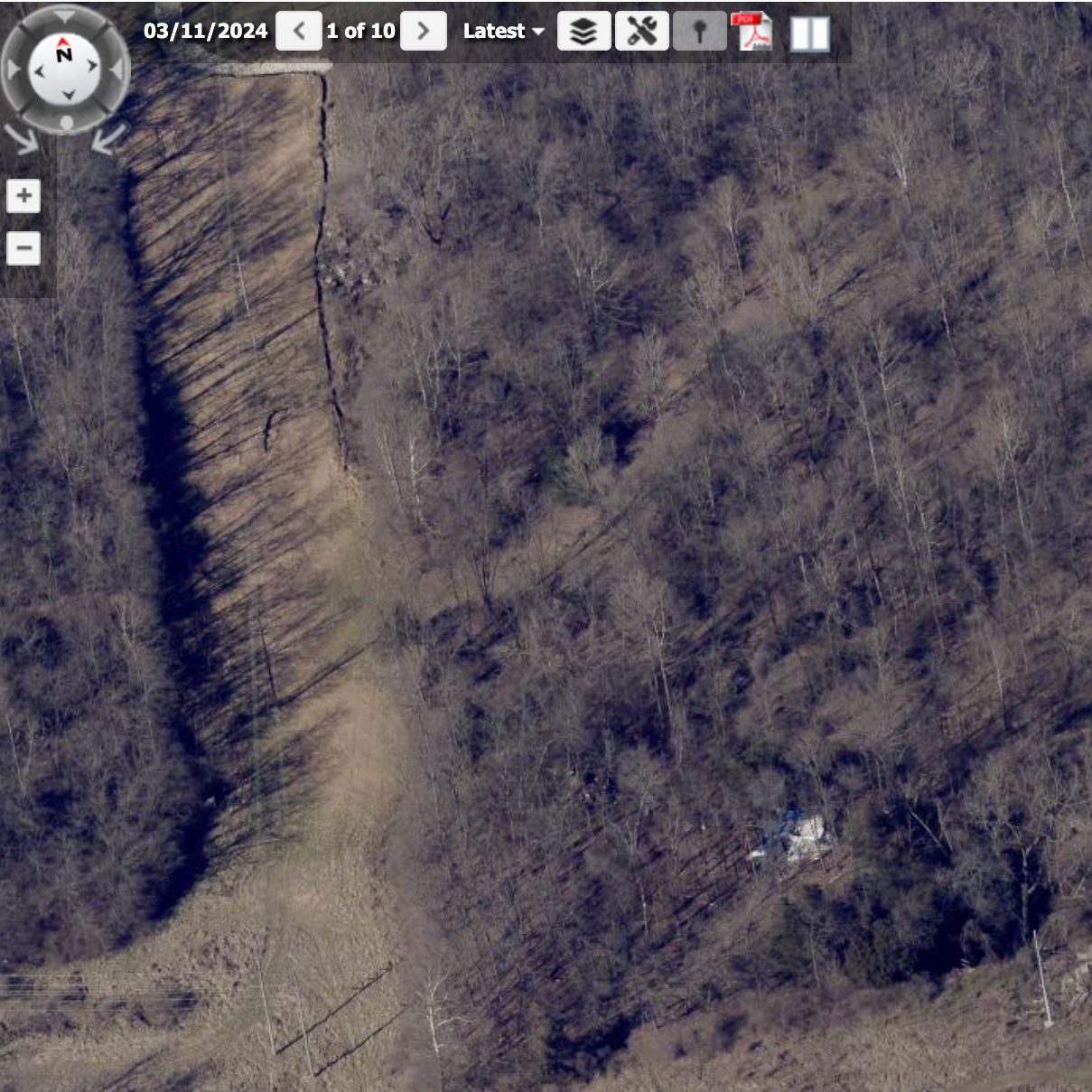

Maps by The B Square. Left: Overview map showing general vicinity of two encampments. The Browns Woods encampment is the western-most square. Middle: Browns Woods (city of Bloomington action. Right: Thomson property (Monroe County government action). [link to dynamic map]

From the public mic on Thursday morning, sharp commentary came from homelessness activists at the regular meeting of Monroe County Commissioners. They wanted commissioners to add an item to their agenda—to delay until April a planned removal of a homeless encampment that was scheduled for Dec. 8.

By late Friday, the activists had won what probably counts as an locally unprecedented victory of sorts—even if they did not get the four-month delay they were looking for. Around 5 p.m., county commissioners issued a news release saying that they’d be putting off the removal of the camp for a week, until Dec. 15.

[Updated Dec. 8, 2025 at 4:45 p.m. The county commissioners have called a special meeting on Teams (a virtual electronic platform) for Dec. 10, 2025 at 7 p.m. for the purpose of a discussion with concerned residents about issues related to the homeless encampment at the county-owned property off Rogers Street. But see subsequent update.]

[Updated Dec. 9, 2025 at 5:58 p.m. The Wednesday meeting topic has been moved to Thursday, Dec. 11 at 1 p.m. in at the historic courthouse where commissioners normally meet. Indiana’s Open Door Law requires a physical location for meetings of governing bodies, so the calendar item on the Monroe County government now reads: “Due to a need to have a physical site for a meeting, Community Conversation has been added to the Commissioners work session to be heard at 1:00 p.m. [on Thursday].”]

Among the considerations highlighted by the activists was the cold weather—forecasted overnight lows in the teens—which made it crucial to ensure the re-location of the tarped structures that encampment residents use to keep warm. The relocation of an estimated 40-50 people, with their cold-weather gear, was not something that could be coordinated in the one week that encampment residents had been given, activists said. The notices were posted and distributed on Dec. 1.

The encampment is located inside Bloomington city limits, but owned by the county government—off Rogers Street in the woods behind the Duke Energy substation. It’s commonly called the Thomson PUD property. (There’s no connection to Bloomington’s mayor.)

County commissioner Jody Madeira is quoted in the news release saying, “[B]y agreeing to postpone the relocation for one week, I hope we are able to provide … the necessary time to meet and coordinate with every individual in the encampment and to make sure they have clear pathways to shelter, services, and long-term support.”

Madeira’s statement continues, “This is not just about moving a site—it’s about doing right by our unhoused community members and helping to ensure the transition is orderly, humane and grounded in our shared commitment to safety, dignity and connecting our unhoused neighbors to available community resources.”

Also quoted in Friday’s news release is Shelbie Porteroff, who spoke from the public mic during Thursday’s meeting. Porteroff said that she “hopes that [we] can continue to work with the county for better solutions and underscore the importance of not evicting during the winter.”

Thursday’s meeting of the county commissioners

At their Thursday morning meeting, when the three commissioners—Julie Thomas, Lee Jones, and Jody Madeira—gave no indication they’d consider adding an item to their agenda about delaying the camp removal, activists started belting out the lyrics: “When I find myself in times of trouble, Mother Mary comes to me …”

As the Nat U. Hill Room at the historic county courthouse was filled with the chorus of the familiar Lennon-McCartney tune, “Let it Be,” commissioners recessed their meeting.

It wasn’t all Beatles tunes. Remarks from activists included accusations that the commissioners were committing “murder by proxy” with a decision to allow the encampment removal to go forward. About 10 minutes after the first recess, an attempt to re-start the meeting failed, but after another 20 minutes, county commissioners were able to resume their meeting and complete the business on that day’s agenda.

During regular public commentary time, activist Sidd Das was pointed in asking commissioners to add an item to their agenda.

He alluded to a statement of values that the commissioners recite to start all of their meetings, which includes the line: “We affirm the right of every person to live peacefully and without fear, and we will fight and resist at every step discrimination and harmful policies, whatever their source.” Das said to commissioners: “In your opening statements, you all stated that your role is to fight any injustices that you see within your community.”

Das continued: “If you actually plan to fight injustices, you would not allow [the encampment removals] to occur. So what you can do, and what we ask you to do, is to add a vote to this agenda to stay the evictions that have been posted at two locations around town, forcing dozens of people to relocate until the spring. Is this something that you will do?”

Monroe County, City of Bloomington: Coordination?

The two locations mentioned by Das were not both under the control of the county government. The city of Bloomington had also posted notice of a pending encampment removal, for the Browns Woods land, on the west side of town, with a deadline of Dec. 8.

On Friday, the city of Bloomington issued a news release about the Browns Woods encampment removal. The matching deadlines of Dec. 8 for the city and county were a coincidence.

Brian Giffen, the city of Bloomington’s homelessness response coordinator, responded to an emailed B Square question by writing, “The City’s 30-day notice for Browns Woods and the County’s 7-day notice were issued independently. There was no coordination around timing.”

The difference in the timeframe for the posted notice to leave—30-days compared to one week—stems from a difference in protocols for encampment removal used by the city and county governments. At least for the timeframe for posted notice, the city of Bloomington follows something akin to the guidance from South Central Housing Network (SCHN) on the topic, which calls for 30-day notice.

Also a feature of the SCHN guidance for closures is the idea that encampment residents should be paid to help clean the encampment.

Monroe County’s approach to cleaning up encampments is to contract out the work. For the cleanup at the Thomson property off Rogers Street, county commissioners had more than four months ago, at their July 24, 2025 meeting, approved a $35,000 contract with Bio-One out of Indianapolis for “proper disposal of hazardous materials and general garbage.”

The total non-to-exceed amount came from an estimated cleanup time of 7 to 10 days at $3,500 per day. It’s not clear why a clearance of the encampment was not pursued sooner after the contract with Bio-One was approved.

Legal authority

According to Julie Thomas, who is the current president of the board of county commissioners, it’s the commissioners who have the decision making authority when it comes to encampment closure. That stems from the fact that commissioners oversee all the buildings and real estate for the county government. It’s the county’s fleet and facilities director, Richard Crider, who is handling the logistics for the encampment removal.

Another source of authority for county commissioners is local Monroe County code. That code says it is “unlawful for any person to camp, occupy camp facilities, or use camp paraphernalia on any property owned or controlled by Monroe County, Indiana, government without the express permission of the Board of Commissioners of the County of Monroe, Indiana.”

So far, the Monroe County sheriff has not played a law enforcement role in connection with the Thomson PUD encampment, according to the sheriff’s office. Monroe County sheriff Ruben Marté gave a statement on Friday, that includes his appreciation for the action by the commissioners to delay the removal for a week: “I appreciate the Monroe County Commissioners for taking the necessary time to

ensure that the transition at the Thompson property is handled smoothly, safely, and humanely.”

Marté’s statement continues: “Upholding the law is essential, as is respecting the legitimate concerns of the neighboring property owners whose quality of life and safety matter deeply to me.”

It’s the concerns of neighboring property owners, including those who live in the Osage Place neighborhood, which was built by Habitat for Humanity, that have been cited as one reason for proceeding with the displacement of the encampment. When The B Square visited the encampment on Friday, one resident gestured towards the Osage Place development as what he figures the likely cause is for the county government’s action.

Camp visit

When the B Square paid a visit to the camp on Friday morning, one resident was sifting through some of the snow-covered camp detritus looking for his lost wallet. It was blue, he says. The color impedes the search, because there are pieces of blue tarp mixed into the bicycle parts, sledgehammer, and other camp clutter that’s lying around.

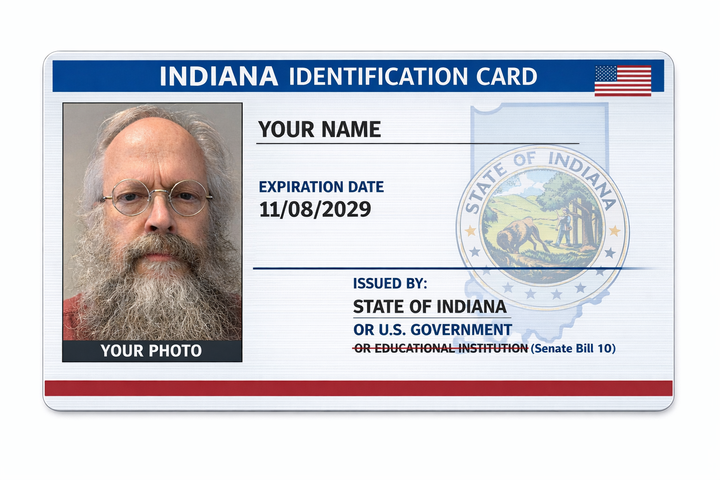

The wallet had his money as well as his ID cards. He settles on the idea that a guy who had been around before must have seen him drop his wallet, picked it up and left with it. He seems resigned to not finding his wallet, but heads out of the encampment in search of an opportunistic wallet thief.

A flexible metal clothes-dryer exhaust tube is serving as a chimney, sending smoke skyward from a wood stove inside a well-tarped structure. Inside, speaking through several layers of tarp, is a man who says to just call him “Carl.” That’s not his name. He says he built the wood stove himself.

Carl says he’s lived in that same spot for three years, but knows others who have lived farther back in the woods for as long as a decade. He thinks the current pressure on the camp to move is from a nearby new development—it’s the Osage Place project by Habitat for Humanity.

He says that new arrivals at the camp sometimes “stir up trouble,” and that leads to pressure from authorities to get people to move.

On the question of the written notice that was given to leave the place, he says that flyers were posted and handed out. He says the estimates that there are between 40 and 50 people living in the encampment sound about right, but he’s not certain.

Carl also talks about surveillance of the camp. He says he has heard and seen drones flying over the camp. [According to Monroe County sheriff's office, drones have in the past been deployed to monitor encampments, but not for the current situation at the Thomson property. ] He says it’s understandable that the fire department might want to check out smoke coming from tarp-covered structures.

Carl says he grew up in Middle Tennessee and describes a long work history as an electrical superintendent and later in fiber optics. He says he was paid several thousand dollars to relocate from Tennessee to Wyoming to oversee crews installing and automating oil and gas wells, and that he worked for or around major companies in that sector. He mentions supervising large crews—on one job, it was a crew of 72 people. Later, he did additional training in fiber optics, and worked as a fiber optic splicing technician and network engineer, helping design a network, doing commercial and residential installations.

Over time, Carl got burned out. Jobs got bigger, timelines got shorter, and there was less money for doing the work. He’s got health challenges that mean he can’t walk very far. From the woods, he can walk as far as to the splash pad in Switchyard Park, but not past that. He’s worried about being able to physically move his belongings or relocate easily.

Carl says that he used to think people in camps like this were all “drunks and druggies.” Now, based on his own situation and what he has seen of others living in the woods, he doesn’t believe that.

Carl does not know where to move next. Faced with the notices and the expectation from authorities that people will leave, he says he doesn’t know where to go—he wishes there were a place they could move to that had been thought through in advance. He thinks he still has the job skills to lift himself out of his situation.

Scenes from the Dec. 4, 2025 meeting of the Monroe County board of commissioners. Left: Shelbie Porteroff addresses fellow activists during the meeting recess. Middle: Sidd Das (green shirt) and Gabriel address fellow activists during the meeting recess. Right: The meeting has resumed, and activists mingle with sheriff's deputies: “Thank you for not arresting me.” (Dave Askins, Dec. 4, 2024)

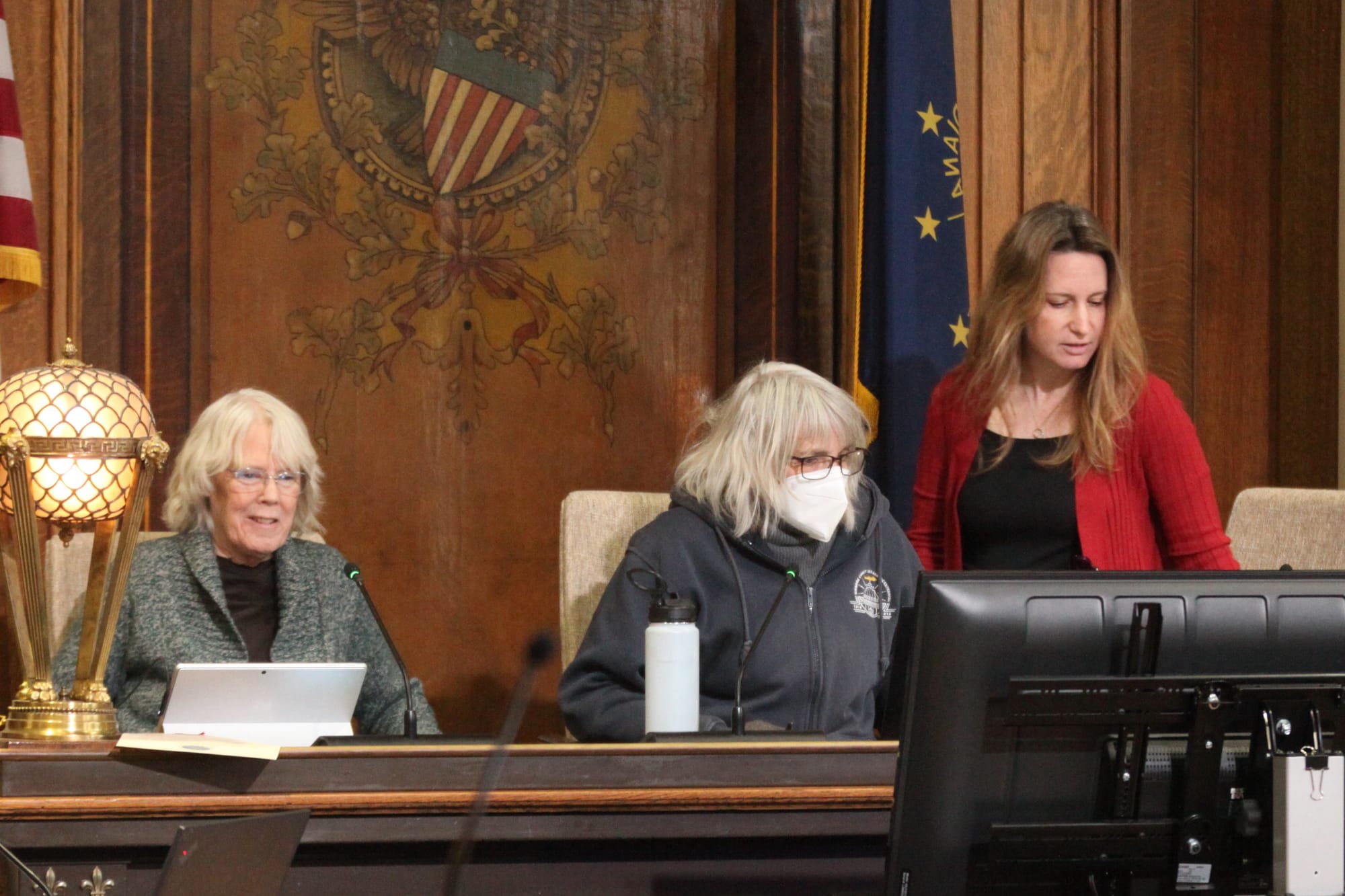

County commissioners left the dais during the recess (left) but then returned (right). From left: Lee Jones, Julie Thomas, and Jody Madeira. (Dave Askins, Dec. 4, 2025)

The aerial flyover imagery is from the Eagleview module of Beacon, which is the geospatial information platform used by Monroe County government. It's from the March 2024 flyover, which illustrates that the encampments have been in place for over a year and a half. Left: Browns Woods. Right: Thomson PUD

Comments ()