Indiana Supreme Court hears Bloomington’s constitutional annexation challenge over voided remonstration waivers

The Indiana Supreme Court heard arguments in Bloomington’s annexation case, testing whether cities can claim constitutional protection when the legislature voids their contracts. Justices focused on conflicts between two appellate rulings and the scope of Home Rule.

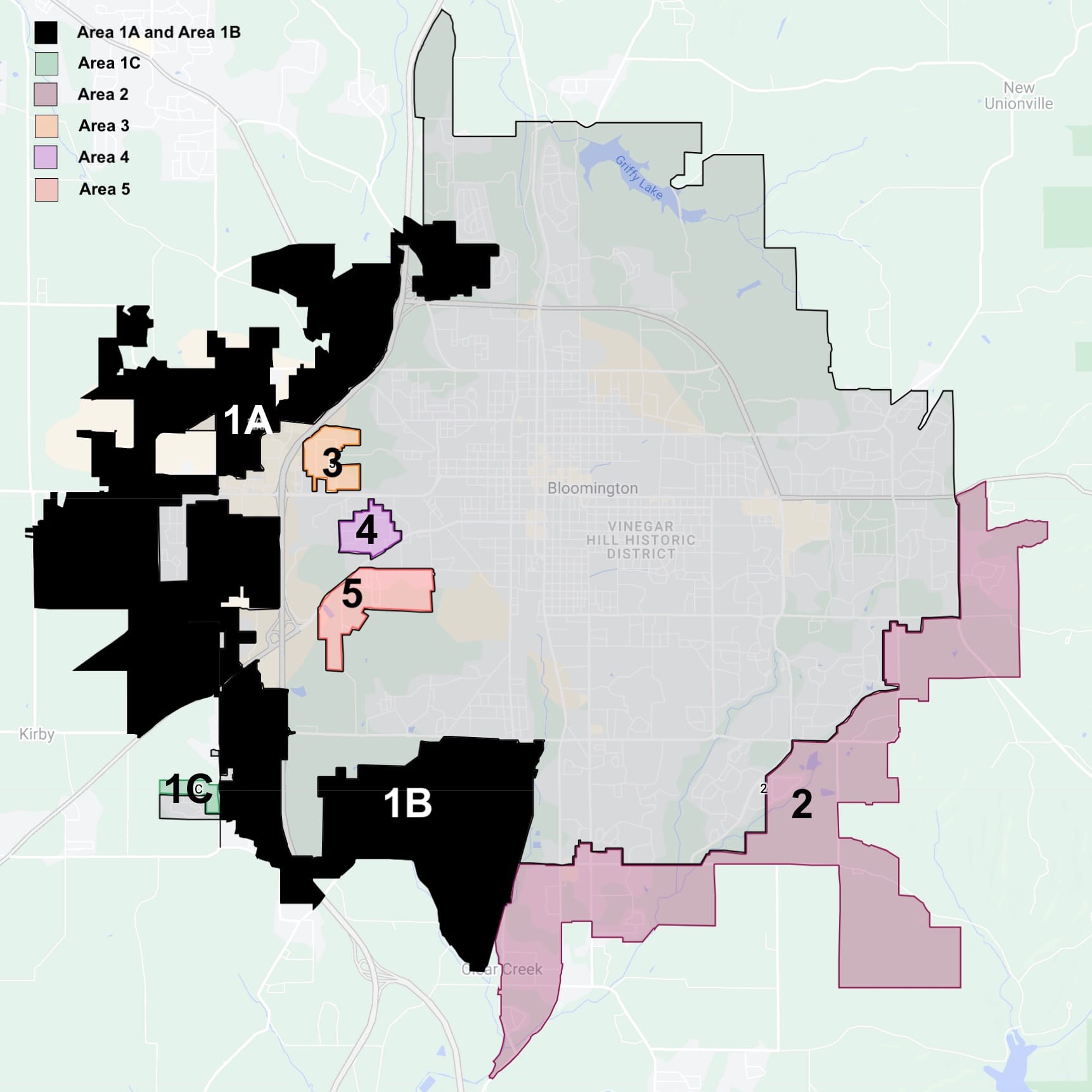

Left: The areas rendered in black, Area 1A and Area 1B, had their lawsuits with constitutional claims dismissed by the city. The remaining five five areas, shown in different colors are subject of the consolidated lawsuits with a constitutional claim. RIght: Indiana Supreme Court justices from left: Geoffrey G. Slaughter, Mark S. Massa, Loretta H. Rush, Derek R. Molter, and Christopher M. Goff (Screen grab from Oct. 30, 2025 livestream.)

The Indiana Supreme Court heard oral arguments on Thursday (Oct. 30) in a case that could clarify how much constitutional protection local governments have when the General Assembly changes their legal powers.

The five judges who heard arguments were: Loretta H. Rush, Mark S. Massa, Geoffrey G. Slaughter, Christopher M. Goff, and Derek R. Molter.

At issue in the case is a 2019 law that voided hundreds of remonstration waivers that Bloomington obtained from property owners over several decades. Those waivers—signed in exchange for sewer service—barred current and future owners of the land from opposing future annexation in formal remonstrance proceedings. Bloomington contends that the legislature’s decision to nullify the waivers violated the Indiana Constitution’s prohibition on laws impairing contracts.

Because the waivers were voided, the signatures of many landowners were counted in the remonstrance tally done by the Monroe County auditor—which resulted in a count that was high enough to stop annexation. If those signatures by owners of property with attached waivers had not been counted by the auditor, the tally would not have been enough to stop annexation. That’s why the county auditor is the named defendant in the lawsuit.

Earlier this year, a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals rejected the city’s argument, relying on precedent that says municipalities are “creatures of the state legislature” and therefore cannot invoke the contracts clause against the state itself. Writing for that panel, Nancy Tavitas said Bloomington lacks “enforceable rights” under either the state or federal constitution, because cities act only through powers granted to them by the legislature.

But a separate appellate decision in May of this year on a similar case (Rokita v. Board of School Commissioners for the City of Indianapolis), pointed to a different conclusion. In that case, a different Court of Appeals panel ruled that the Indianapolis Public Schools Board could raise a contracts clause challenge when lawmakers retroactively revoked an exemption affecting an existing property-sale agreement.

The judges in the Rokita case held that applying the new law would “substantially impair” the board’s contractual rights under Article 1, Section 24 of the Indiana Constitution.

It was those conflicting rulings that set the stage for Thursday’s hearing. Bloomington’s position was that if the legislature can erase its annexation waivers, no local government can rely on the stability of any statutory agreement—from school-building leases to bond covenants.

The state argued that because cities and other political subdivisions only exist because the legislature created them, they cannot claim constitutional protection from the legislature. While the contracts clause protects private parties, a local government is not a private party and thus does not enjoy constitutional protection from the contracts clause—so goes the state’s argument.

It turns out that even though the Supreme Court agreed to set Thursday’s hearing, the exact wording in its order fell short of granting transfer. In its order setting the oral arguments that took place on Thursday, the Supreme Court said only that it “has determined the above-captioned case merits oral argument.”

That’s not synonymous with agreeing to accept transfer of the case. When the Indiana Supreme Court agrees to accept transfer, it takes over the case from the Court of Appeals and wipes out the lower appellate opinion. When it denies transfer, the Court of Appeals ruling remains the law.

On Thursday, Chief Justice Loretta Rush started the hearing by laying out the first question to be decided by the court, which was whether the court should even accept transfer of the case. Rush bookended the proceedings by thanking everyone and saying, “We will be discussing the case with the first issue being the issue of transfer.”

It’s rare for oral arguments to be held when transfer has not already been granted. And it’s rarer still for transfer not to be granted after oral arguments are heard. But it does not mean it’s automatic that transfer will be granted, just because oral arguments have been heard.

On May 22, 2023 the Indiana Supreme Court denied transfer in an adoption case after hearing oral argument in March. On May 23, 2023, the court revoked transfer after oral arguments in a case involving “inactive registration” for a car. On Nov. 8, 2019 the court heard oral arguments in a 2000 murder case and the same day reversed its earlier decision to accept transfer.

Outside counsel for the city of Bloomington, Andrew McNeil, with Bose McKinney & Evans, opened with the basic argument based on conflicting rulings in the Court of Appeals:

Now the Court of Appeals in this case determined that Bloomington could not avail itself of the protections of the contracts clause because it was an instrumentality of the state. But 87 days later, a different panel of the Court of Appeals in the Rokita versus Indianapolis Public Schools case rejected the holding of the Bloomington panel and said, to hold that the General Assembly, absent a valid exercise of its necessary police power, can retroactively impair the … contractual obligations of a political subdivision and their contractual partners, creates uncertainty around those transactions, increases costs to taxpayers and renders the protections of Article One Section 24 illusory. … We think it would be appropriate for this court to grant transfer and to sort through the thorny issues that those cases present.

The Court of Appeals in the Rokita case relied on the Home Rule Act. Justice Massa said that in the Rokita case, the Court of Appeals “seemed to sweep away a century of case law on this issue and attribute that conclusion to the Home Rule Act.” He said to McNeil: “Explain to me why the Home Rule act abrogates precedents of this court in this regard.”

McNeil first pointed to the line of cases that would be overturned if the court found in Bloomington’s favor which started in 1934 (Bolivar Township v. Hawkins). But Massa pressed McNeil on the question of how the argument actually goes that relies on the Home Rule Act, asking: “But how does that convert local government into being on the same footing with private parties, who are clearly protected by this contracts clause?”

McNeil’s answer was longer than this, but began with, “That’s a many-layered question, your honor.”

Presenting the state’s case was James Barta, solicitor general in the attorney general’s office. Barta said the court should deny transfer for three reasons. First, Bloomington had not identified any “clear error” in the prior six cases where the Supreme Court had found that legislation releasing private parties of contractual obligations owed to the government does not offend the contracts clause.

Second, even if the contracts clause applied, it would not affect the outcome of Bloomington’s case, because the Court of Appeals panel had found that the nullification of the annexation remonstrance waivers did not translate into a “substantial impairment of the overall contractual relationship.” Third, the decision in Bloomington’s case does not actually reflect an outright conflict with the decision in the Rokita case.

Justice Molter immediately jumped on the idea that the opinion in the Rokita case did not actually conflict with the opinion of the Court of Appeals in the Bloomington case, asking Barta, “How doesn’t this conflict with Rokita versus Board of Commissioners?” Goff added, “I mean, I thought judge Bailey’s opinion just outright said the Court of Appeals panel decision, this one was wrong, and that our own precedent is very outdated, and so the Court of Appeals shouldn’t follow that.”

Molter was referring to a long footnote [13] which addresses the opinion rendered by the Court of Appeals panel in the Bloomington case.

Barta said, “As I read footnote 13 of that opinion, it really seems to emphasize that applying the legislation to the contract would affect not just obligations owed from private parties to Indianapolis schools, but obligations owed from the schools to private parties. It emphasizes there’s sort of a mutual disruption. And so that’s the opposite situation here.”

Of the five justices, probably the most skeptical of the state’s position was Goff, who told Barta: “I perhaps see this case differently than my colleagues, but I really don’t see this as particularly difficult.” Goff continued, “I don’t think that the precedent that you rely on is applicable in this case, because it happened decades before the Home Rule act in 1980.” Goff added that an annexation waiver is not a kind of contract that the state government ever enters into, and it’s only the local government that enters into that kind of contract.

Barta defended the state’s position by arguing that the Home Rule Act does not actually decide the question—because the important point is not about what powers cities have, but rather the source of their powers, which is the state legislature. Barta pointed out that the Home Rule Act itself could simply be repealed by the state legislature.

Barta also pointed to the origin of the contracts clause of the state constitution, saying that the framers in 1851 made a deliberate choice to make the state protections for contracts run parallel to the federal clause. Barta said, “At that time, it was already well established in federal law that cities could not invoke the federal contracts clause against their states.”

It’s only Area 1C, Area 2, Area 3, Area 4, and Area 5 that are subject to the constitutional lawsuit heard by the Supreme Court on Thursday. The other two annexation territories, Area 1A and Area 1B, had their lawsuits with constitutional claims dismissed by the city.

A trial on the merits of annexation in Area 1A and Area 1B has led to a lower court decision against Bloomington and a Court of Appeals ruling affirming the lower court’s decision.

The city of Bloomington intends to petition the Supreme Court to accept transfer of the case involving trial on the merits of Area 1A and Are 1B. The Court of Appeals ruling in that case came on Sept. 24. Under court rules, the city has 45 days to file its petition. So that filing should appear on the case docket in the next week or two.

Comments ()