Judge says key ruling in Bloomington annexation case will come on Sept. 5

After hearing oral arguments for a little more than one hour on Friday morning, judge Nathan Nikirk told attorneys for annexation remonstrators, and for the city of Bloomington, that he’d take their arguments under advisement.

Then he told them he would issue a ruling next Tuesday, the day after Labor Day.

That means on Sept. 5, Nikirk will answer this question: Should the standard annexation trial for Area 1A and Area 1B be put off—until a constitutional question about the status of annexation waivers is resolved?

[Updated Sept. 5 at 3:01 p.m. Nikirk granted the request by remonstrators for a stay on the trial. Here’s a link: Nikirk’s order on the motion.]

Remonstrators filed their lawsuit in March 2022.

Nikirk is the special judge appointed in the case. His home court is in Lawrence County, but the hearing on Friday morning was held at the Charlotte Zietlow Justice Center in downtown Bloomington.

The constitutional question is the subject of separate litigation initiated by the city of Bloomington.

Such waivers are legal documents signed by a property owner, giving up the right to remonstrate against annexation, in consideration of the ability to purchase sewer service from the city.

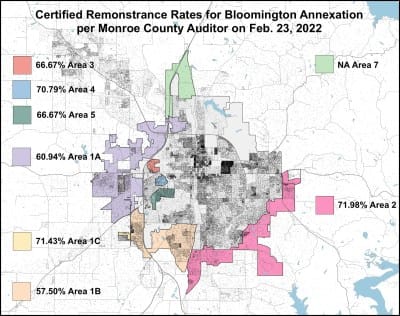

Based on a disqualification of several waivers—resulting from a 2019 law that invalidated all such waivers signed before July 1, 2003—remonstrators in Area 1A and Area 1B gathered enough signatures (more than 50 percent of landowners ) to force a judicial review of the city’s annexation. But they did not gather enough signatures (more than 65 percent of landowners) to stop the annexation outright.

If the 2019 law is found to violate Indiana’s constitution, then the remonstrators in Area 1A and Area 1B will have fallen short of the 50-percent threshold, and there would be no reason to hold the five-day trial that is currently set to start on Nov. 13.

If the city prevails in that other litigation, then none of the other five annexation areas, which under the 2019 law, will have gathered enough signatures to stop annexation. But two of the areas would still have more than 50 percent, which would force judicial review of those two annexations.

For the city’s lawsuit that challenges the constitutionality of the 2019 law, there’s a hearing set for Dec. 10 on the city’s motion for summary judgment, according to the case management plan.

What the remonstrators in Area 1A and Area 1B are seeking to put on hold is the standard trial that has to take place, if remonstrators gather signatures from between 50 and 65 percent of landowners.

When that standard trial takes place, the court is required to order the annexation to go forward, if certain objective conditions are met—and if the city is able to show that the annexation is in the best interest of the owners of land in the territory to be annexed. Among the conditions listed out in the statute is that the population density in a proposed annexation area is at least three people per acre. [IC 6-4-3-13]

That’s a sufficient, but not a necessary condition among the objective criteria. Other sufficient conditions are if 60 percent of the territory is subdivided, or if the territory is zoned for commercial, business, or industrial uses.

In addition to the objective criteria, some subjective criteria would need to be met. The other, more subjective criteria include whether the annexation would have a “significant financial impact” on property owners and whether the annexation would be in the “best interests of the owners of land in the territory.”

In front of Nikirk on Friday morning, Stephen Unger, with Bose McKinney & Evans, argued Bloomington’s side. Bloomington is against putting the scheduled Nov. 13 trial on hold until the constitutional question is resolved in the other lawsuit.

Unger talked about the “need to have a trial.” Collecting signatures from more than 50 percent of landowners gives the remonstrators a right to their “day in court” but “it is not is not a right to obstruct the annexation,” Unger said.

Unger said, “The remonstrators need to stop obstructing the city from completing this annexation.”

Part of the litigation strategy that Unger characterized as “obstruction” included an unsuccessful attempt by remonstrators to convince Nikirk that they had a right to additional time to gather signatures, based on the “pestilence” of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Arguing the side of the remonstrators were William Beggs and Ryan Heeb, with Bunger & Robertson. The key concept they hammered was “subject matter jurisdiction.”

The city of Bloomington had offered in its response to the remonstrators’ lawsuit the constitutional question as an affirmative defense, Beggs said.

After some back-and-forth between Beggs and Nikirk, Beggs eventually indicated the argument was not that Nikirk doesn’t currently have subject matter jurisdiction, but rather that Nikirk’s court would lose subject matter jurisdiction, once the constitutional question came into play.

Beggs said that if the city of Bloomington loses the trial on the merits of the annexations for Areas 1A and 1B, then Bloomington will then try to apply the outcome of the constitutional question, to render Nikirk’s ruling moot.

Beggs said it’s a better use of judicial resources, not to conduct a five-day trial, if it turns out that such a trial is not even needed. Otherwise put, if Bloomington prevails on the constitutional issue in the other lawsuit, then there is no need to conduct a five-day trial.

Nikirk did not seem persuaded by the argument based on the economy of judicial resources—because he gets paid to do the job, he said. But Nikirk did seem persuaded that the imposition of a five-day trial on the remonstrators could be considered burdensome, if that five-day trial were not even necessary.

Unger argued that the city of Bloomington would likely prevail at the annexation trial, even without prevailing on the constitutional question. So the city has the right to see the annexations for Area 1A and Area 1B go through—sooner than at the end of the couple of years that it might take to settle the constitutional question, he said.

Unger described to Nikirk how Bloomington mayor John Hamilton in 2017 took up the “charge” to say, “I’m going to right-size the city boundaries.”

Unger noted that Hamilton’s term comes to an end this year, and he chose not to run for re-election. “I think it’s important…that the mayor has the opportunity to have this remonstrance trial heard …before his term expires, while he is still the mayor of this city.”

The constitutional question in the other lawsuit centers on Article I, Section 24 of Indiana’s state constitution, which reads: “No ex post facto law, or law impairing the obligation of contracts, shall ever be passed.”

And Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution states, “No state shall … pass any … Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts.”

In addition to its constitutional claims, Bloomington is saying that the 2017 start to the current annexation effort should factor into the application of the 2019 law. After Bloomington initiated its annexation effort, but before it was complete, in 2017 Indiana’s General Assembly passed a new law that had the effect of stopping Bloomington’s annexation effort.

That 2017 law was eventually found to be a violation of Indiana’s state constitution by a 3–2 vote of the Indiana Supreme Court. The ruling came in late 2020.

Comments ()