Map of racially restrictive covenants released by Monroe County recorder

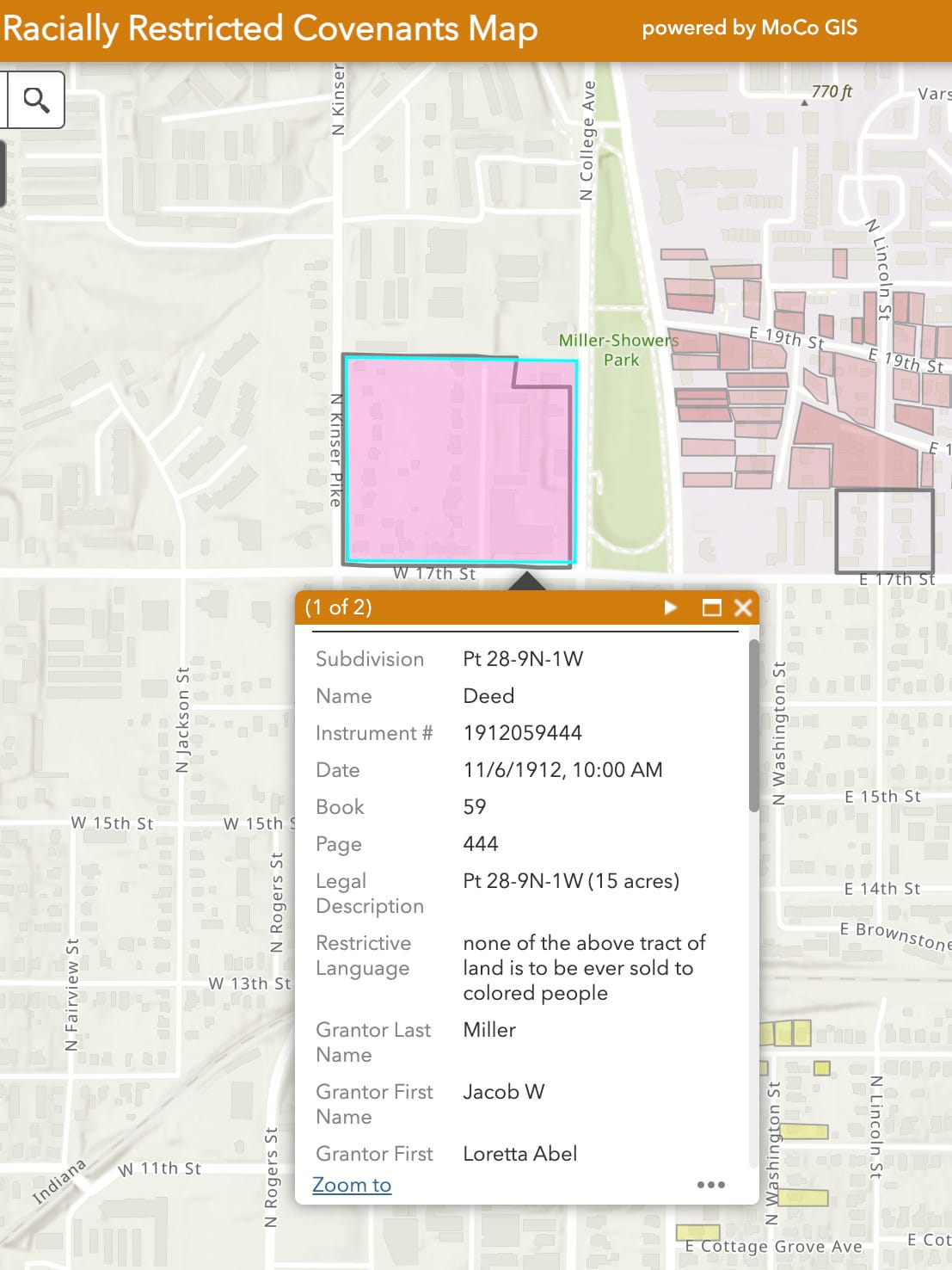

“None of the above tract of land is to be ever sold to colored people.”

That is the text of a covenant recorded on a deed dated Nov. 6, 1912 for some land located at the northwest corner of 17th Street and College Avenue in Bloomington, Indiana.

A point in time that lies over a century in the past might seem like ancient history.

But the same parcel is part of a plat that is dated just 77 years ago—June 16, 1946.

The covenant on the plat reads: “The ownership and occupancy of lots and buildings or parts thereof in this addition are forever restricted to members of the white race, except that domestic help, not of the white race may occupy a room in said dwelling during the period of employment.”

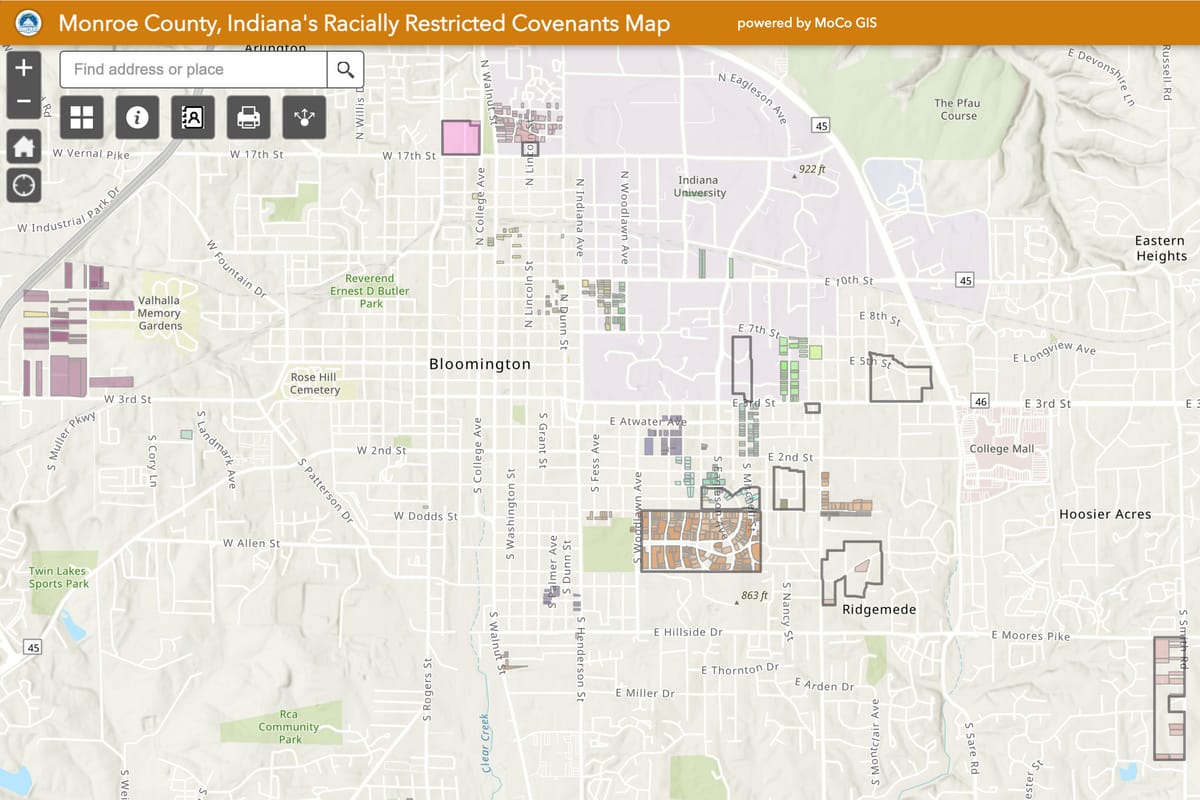

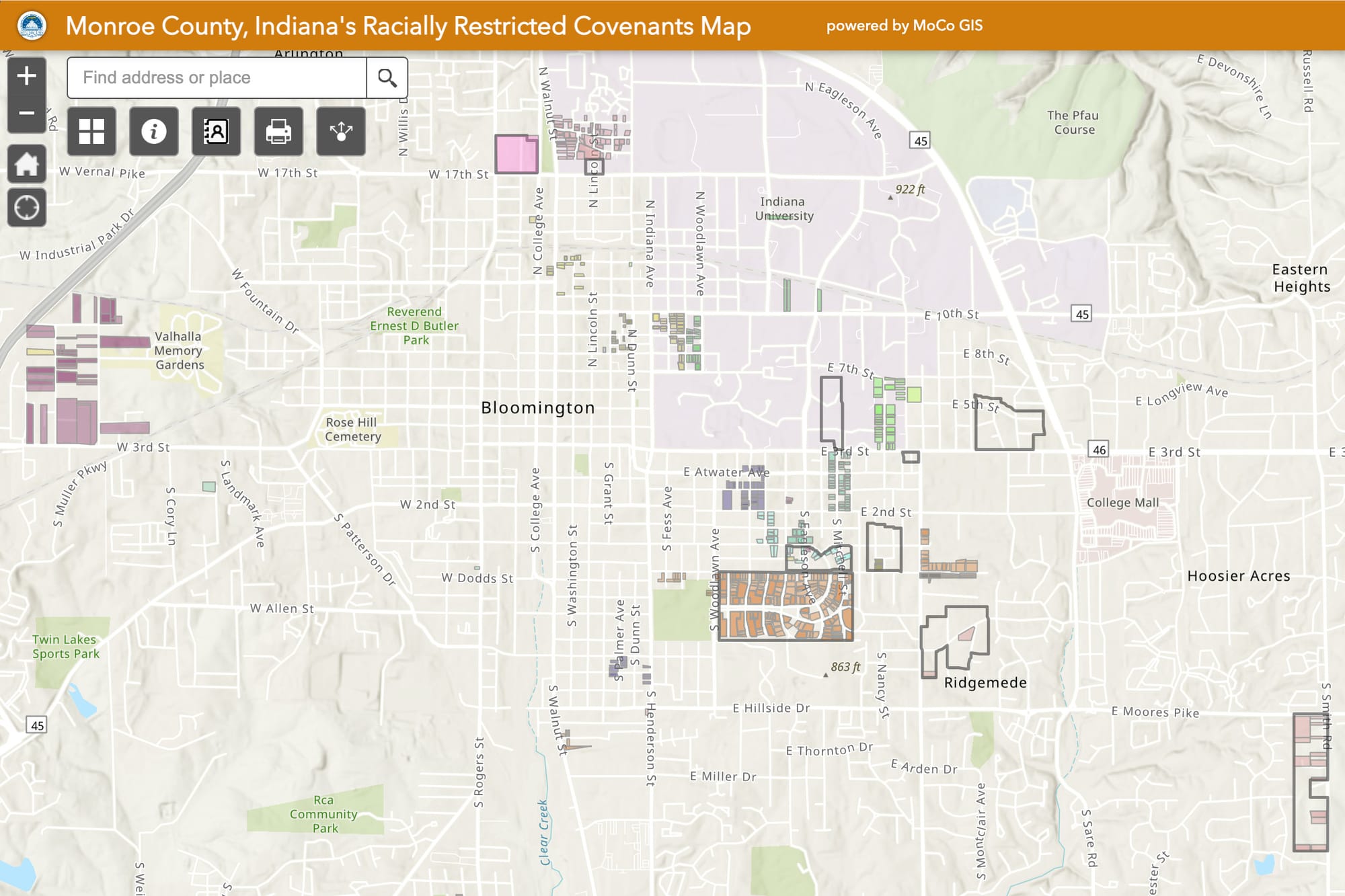

Information on racially restrictive covenants on deeds and plats in Monroe County is now within easy reach of anyone with an internet connection.

This past week, Monroe County recorder Amy Swain released a project that maps out racially restrictive covenants on deeds and plats, which the county recorder’s office has unearthed, scanned and made accessible on a web page.

The map is embedded in an explainer website, but can also be accessed through a direct link.

Swain is the newly elected recorder, sworn into office just about six weeks ago. Her statement announcing the release of the map gave credit to the office led by the previous recorder, Eric Schmitz: “[O]f course, the bulk of the work was done during former recorder Eric Schmitz’s administration.”

Schmitz is now deputy recorder for Swain. At the time when most of the work on the mapping project was completed, Ashley Cranor served as deputy recorder, and pushed the project forward. In 2022, Swain prevailed over Cranor in a close Democratic Party primary.

Reached by The B Square late last week, Cranor had this on seeing the finished map: “All I have to say is: Brilliant! Hats off!”

Cranor continued, “I’m pretty confident that I know which staff person really busted his tail there, and that’s Jason Funk. I won’t be surprised someday if he writes a book about it.”

Swain’s statement also singled out Funk for praise, along with the county’s GIS staff: “Jason Funk, Deputy Recorder, and John Baeten, Ph.D., Monroe County GIS Coordinator, have been instrumental in bringing this project to completion.”

The 1946 date on the plat at 17th and College is not the most recent one on a Monroe County deed that has a racially restrictive covenant.

There’s one dated 1965—even though the Shelley v. Kraemer U.S. Supreme Court decision was handed down in 1948. Shelley v. Kraemer held that restrictive covenants in deeds, which prohibit the sale of property to non-Caucasians, violate the equal protection clause of the Constitution.

The backgrounder the recorder’s office has put together notes that a “repudiation statement” can be filed with the recorder’s office about any piece of property, which would just say that that the restrictive covenant is no longer enforceable and is illegal.

The land at 17th and College is also interesting because of whose names appear on the 1912 transaction—Jacob W. Miller as grantor (seller) and Showers Brother Furniture Factory as grantee (purchaser). Those are the two names that give the nearby park its moniker: Miller-Showers Park.

The explainer that the recorder’s office has put together does not point to the names on the documents as the people who necessarily authored a covenant—it’s a kind of restriction that runs with the land and gets passed along with each property transfer over time.

But the background material provided by the recorder’s office does point out: “Many of these folks were lawyers, businessmen, teachers, state representatives, administrators, quarrymen, lumbermen, and long-established residents of the county.”

Listed as grantor in 14 of the records on the map is Carl Eigenmann, professor of zoology at Indiana University in the 1880s through he early 1910s. The dormitory on the east side of campus is named after him.

In 8 of the 14 records with Eigenmann’s name as grantor, the grantee a second grantor is listed as William Lowe Bryan, who was named Indiana University president in 1902. Bryan Park is named after him.

Comments ()