Next year’s first ruling on a Bloomington annexation lawsuit could depend on meaning of “proceeding”

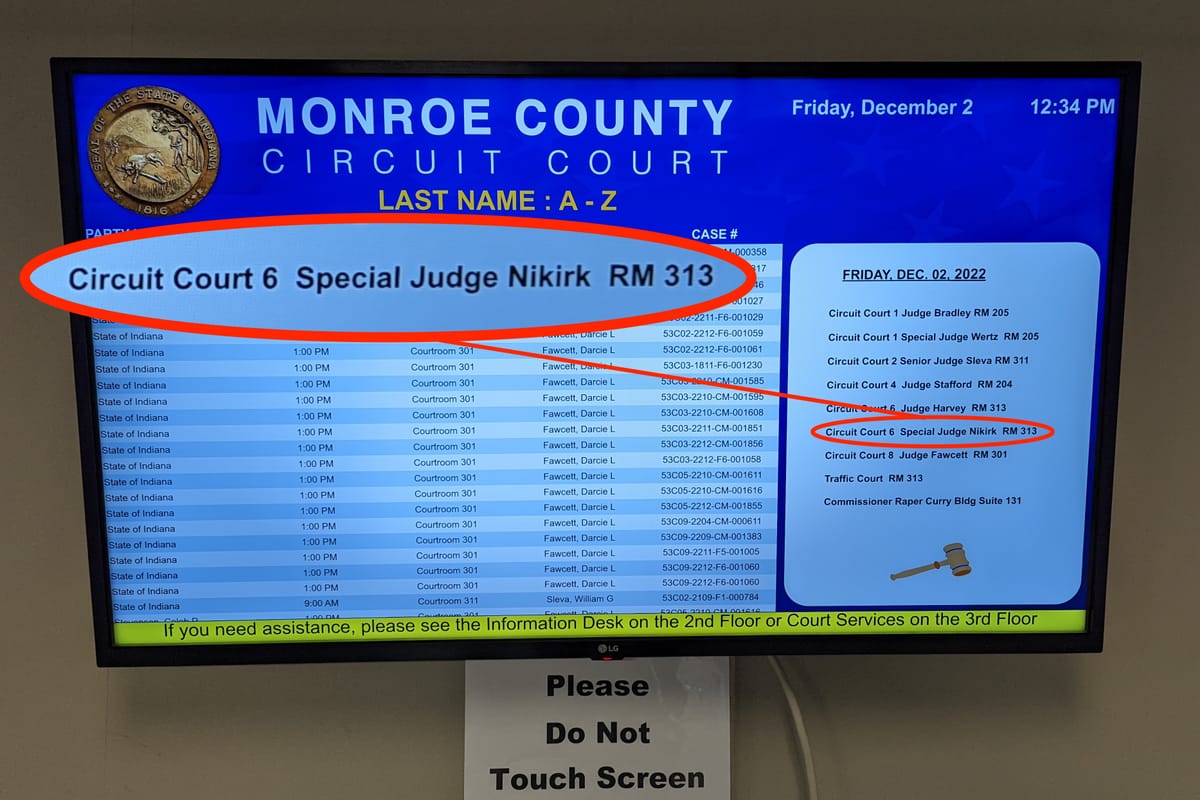

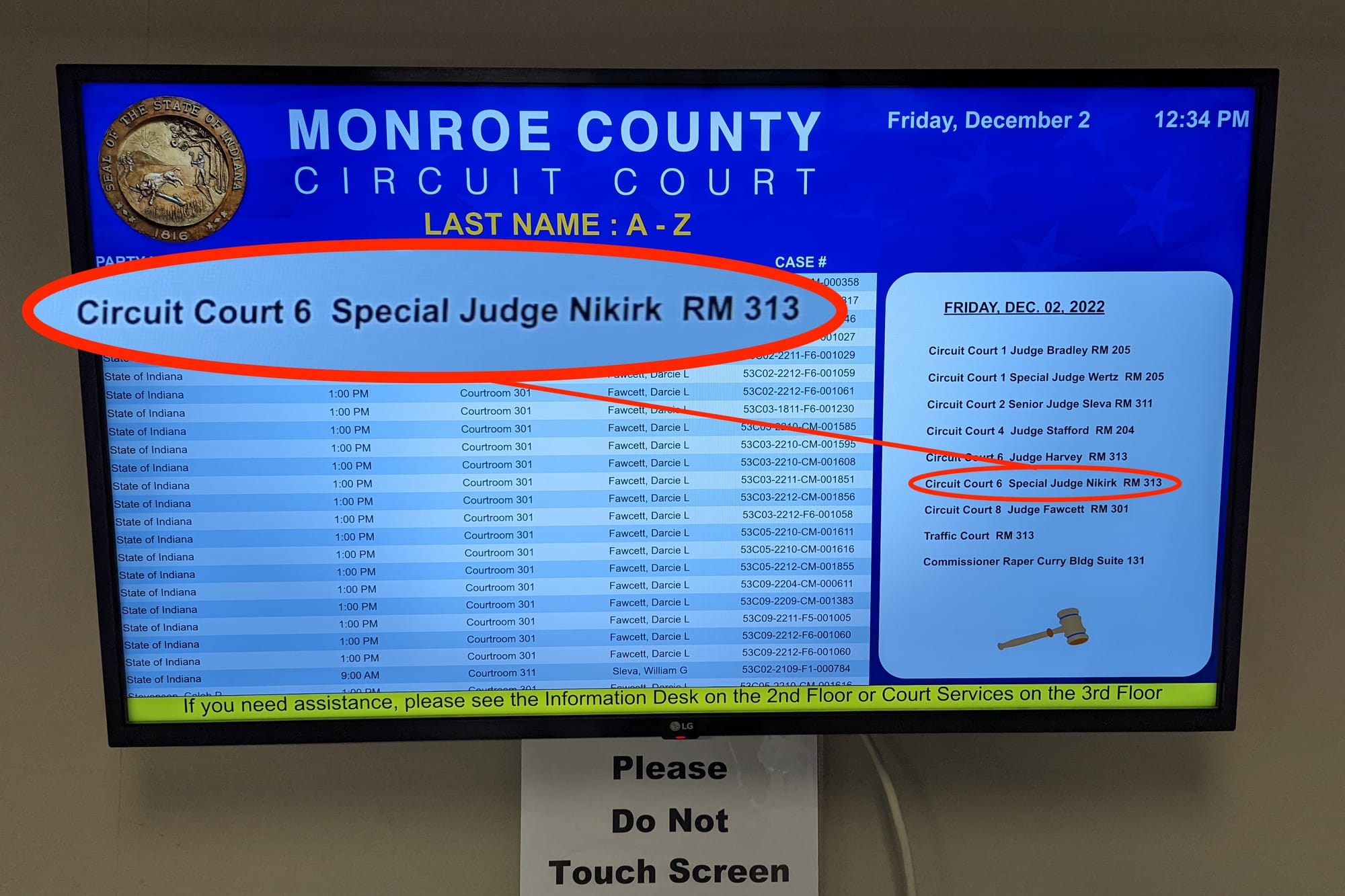

At the end of a Friday hearing that lasted about an hour and 20 minutes, special judge Nathan Nikirk did not issue a ruling in the case that remonstrators against Bloomington’s annexation have brought to the court.

Friday’s hearing involved the remonstrators in Area 1A and Area 1B, who collected signatures from more than 50 percent of land owners, which was enough to qualify for judicial review, but fell short of the 65 percent threshold that would have stopped annexation outright.

Area 1A is just west of Bloomington. Area 1B lies to the southwest.

Remonstrators in those two areas are asking that the judge grant them additional time for signature collection, under a state statute that provides certain emergency powers. [IC 34-7-6-1] The emergency in question is the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite the fact that the judge didn’t issue a ruling on Friday, based on the clarification that Nikirk requested from both sides during the hearing, his eventual decision could depend on the interpretation of the word “proceeding” as used in the statute on emergency powers. Nikirk wanted both sides to lay out how they understand the concept of “proceeding” under that statute.

The statute refers to the emergency powers as applying to a “proceeding…pending before a court, a body, or an official, that exists under the constitution or laws of Indiana.”

At the end of the hearing, Nikirk asked both sides to prepare proposed orders on the question by Jan. 6, 2023.

Nikirk’s ruling on the question of a time extension will by no means settle the question of whether annexation happens, either in Area 1A or Area 1B, or the other areas, which are also subject to pending litigation.

On Friday, the attorney for the remonstrators, Bill Beggs, argued that because the collection of remonstrance signatures is part of the overarching proceeding of the annexation process, the judge has the authority to apply the emergency powers statute. Applying the emergency powers statute would allow the judge to extend the 90-day signature collection period for an additional 90 days, according to the remonstrators.

That is, the position of the remonstrators is that they can be given additional time to add to the signatures that have already been collected.

Assistant city attorney Larry Allen argued Bloomington’s position, which is that the annexation process is composed of a series of separate proceedings, and that there’s a clean break between them.

Specifically, Allen said there’s a clean break between two of the proceedings: signature collection; and the judicial review that the statute calls for. It’s only after the county auditor certifies the results of the signature collection that the court’s review can start, Allen added.

That means that the process that is currently pending in front of the court had not started until after the signature collection was completed, according to Bloomington’s position. The proceeding of signature collection is no longer pending, according to Bloomington’s position.

So Bloomington’s basic position is that the emergency powers statute cannot now be applied to signature collection for remonstrance against annexation.

But Bloomington also takes the position that if the judge were to apply the emergency powers statute, then the initial 90-day period for signatures would have to be excluded, meaning that no signatures collected during that time would count.

So according to Bloomington’s position, the only option for the judge, if he were to apply the emergency powers statute, would be to restart the signature collection process from scratch.

If no additional time is granted for signature collection, the regular judicial review of the annexations of Area 1A and Area 1B could continue, separate from the lawsuits that Bloomington has filed in connection with the other annexation areas.

The lawsuits filed by Bloomington are about the validity of remonstrance signatures, based on waivers signed by property owners. In those areas, the remonstrators hit the 65-percent threshold, which would stop annexation—except that Bloomington has challenged the validity of many of the signatures.

If additional time for signature collection is granted in Area 1A and Area 1B, that likely means that Bloomington’s waiver-based lawsuits will maintain a holding pattern. After the additional time, if Area 1A and Area 1B were to both achieve the 65-percent threshold for stopping annexation, then those areas would be in the same situation as the other areas, and it would make sense to handle all those areas as one single, consolidated matter.

If Nikirk grants no additional time, or if the 65-percent threshold is not met after additional time, then Area 1A and 1B will be in a different situation than the other areas, which have met the 65-percent threshold.

But a common question of law would still apply to the waivers in all areas: Could the state legislature invalidate all waivers signed before July 1, 2003 by enacting a law in 2019?

Comments ()