Opinion: Bloomington’s plan commission violated Indiana’s Open Door Law, so I filed a lawsuit

The B Square’s report on the plan commission’s meeting last week was headlined with a question: Did Bloomington plan commission meeting follow state law on electronic meetings?

After talking to a half dozen different experts on Indiana’s Open Door Law, I think the answer to the headline’s question is: No.

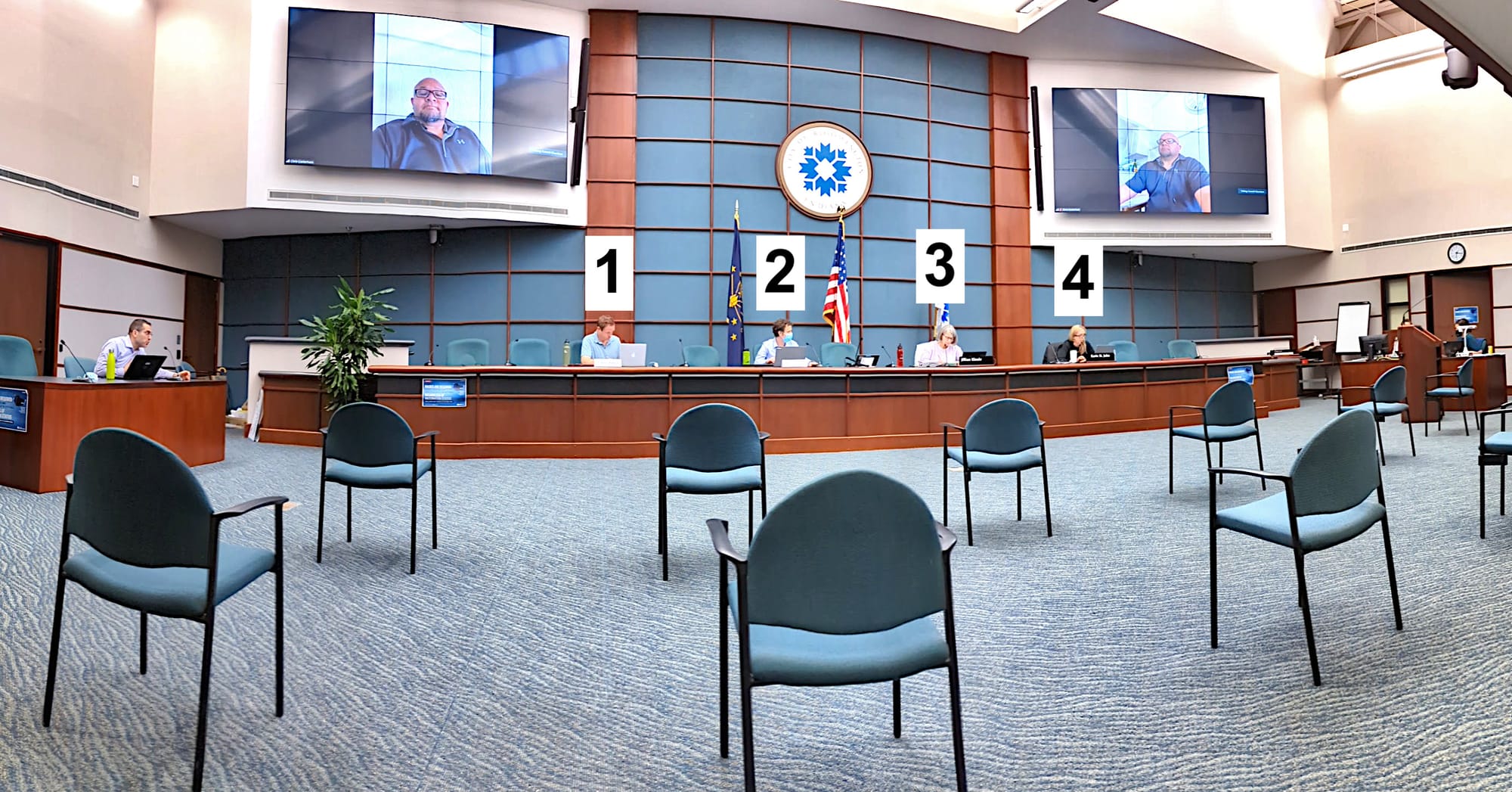

That is, Bloomington’s plan commission violated the Open Door Law with its March 14, 2022 gathering, which was conducted on a hybrid in-person-electronic platform. Four plan commissioners were physically present. Two participated through a Zoom video-conference interface. And three were absent.

When Indiana governor Eric Holcomb rescinded his emergency health order on March 3, that meant government meetings could no longer be held purely on an electronic platform.

Without an emergency order, governing bodies like the Bloomington plan commission have to rely on a 2021 amendment to the Open Door Law (ODL) in order for any of its members to participate in a meeting without being physically present.

So the problem with the March 14, 2022 plan commission meeting was not the fact that some members participated and voted without being physically present. It was the fact that the plan commission failed to follow a key requirement of the amended Open Door Law.

Here’s how that requirement reads:

5-14-1.5-3.5(g). At least fifty percent (50%) of the members of the governing body must be physically present at a meeting.

If there are N members of a governing body, then on any normal understanding of 5-14-1.5-3.5(g), the number of members who are physically present has to be at least 50 percent of N.

In the case of Bloomington’s plan commission, the 50-percent requirement means at least five members (50-percent of nine) have to be physically present.

Responding to an emailed B Square question, Bloomington city attorney Mike Rouker gave the 50-percent requirement a different interpretation, in order to justify the physical presence of just four plan commissioners at the March 14, 2022 meeting.

For Rouker, the 50-percent requirement applies just to the universe of plan commissioners who are attending the meeting, either electronically or in person, not to the universe of sitting plan commissioners.

Rouker points to other paragraphs of the amended ODL, which say electronic participants count towards a quorum, and that if an electronic participant at a meeting loses their connection, the meeting can still continue as long as the sum of in-person participants and electronic participants is a quorum.

Rouker wrote: “The only way these two provisions make sense is if the denominator used when calculating compliance with the 50-percent requirement is based on members attending any particular meeting.”

For Rouker, the March 14, 2022 plan commission gathering was a legal meeting, because four of six is at least 50 percent.

I think the logical mistake in Rouker’s reasoning is to equate “at least 50 percent” with the notion of a quorum, which is typically a majority (i.e., greater than 50 percent) of members.

For a governing body that has an odd number of members, the idea of “at least 50 percent” reduces to the same thing as a majority. But for a governing body with an even number of members, those concepts diverge. For a nine-member commission with one vacancy, a quorum defined by a majority is still five. But at least 50 percent of eight is just four.

Even if Bloomington’s legal department cannot necessarily be expected to defer to the argument of an independent journalist, I think it is reasonable to expect some deference to the view of Indiana’s public access counselor, Luke Britt.

In his widely disseminated guidance on the topic of the amended ODL on electronic meetings, Britt gives a full-throated endorsement to the interpretation of IC 5-14-1.5-3.5(g) as meaning exactly what it says.

The public access counselor’s guidance states (emphasis in original):

The lynchpin to electronic participation by local governing body members is the physical presence of at least 50% of sitting board members, i.e. total membership of the board at the time of the meeting. Ind. Code §5-14-1.5-3.5(g). If less than 50% cannot attend in-person, the meeting must be canceled or postponed. This is an important fail-safe to ensure transparency.

Rouker attended the plan commission’s March 14, 2022 gathering and almost certainly would have been aware that only four plan commissioners were physically present.

Was Rouker aware of that widely-publicized guidance from the public access counselor before the plan commission’s gathering of March 14, 2022? Apparently not. But he was apparently also not 100-percent convinced of his own interpretation of the 50-percent requirement.

On the morning of March 14, 2022, Rouker sent an email message to the public access counselor asking about the correct interpretation of the 50-percent requirement. Rouker wrote: “I have not seen any specific guidance on the proper denominator in your advisory opinions or from any court. Are you aware of any formal guidance on this question?”

Rouker did not get a response from the public access counselor before the plan commission met. The response came the following day. The public access counselor’s direct advice to Rouker was the same as the guidance that he had already disseminated.

After hearing back from the public access counselor, Rourke emailed The B Square. There was no admission from Rouker that the plan commission had violated the Open Door Law. However, he did say that in the future, the plan commission would follow the public access counselor’s interpretation.

Rouker wrote: “For the avoidance of any doubt, we’ll be following the guidance we received from the PAC [public access counselor] today for future hybrid meetings.”

I don’t think that’s good enough. There was never any doubt about the correct interpretation of the 50-percent requirement.

The guidance Rouker received personally from the public access counselor was exactly the same guidance that had been publicly disseminated. And once Rouker became aware of it, he reversed course.

It’s remarkable that Bloomington’s legal department was not previously aware of the public access counselor’s guidance. Based on the Internet Archive, at least as early as July 1, 2021, the office of the public access counselor created a prominent link on its home page to the electronic meeting guidance:

And a general Google search for the string “indiana pac guidance on electronic meetings” yields as the first result the .pdf file containing the public access counselor’s guidance.

It’s a good thing that Bloomington’s city attorney has given an assurance that the plain wording of the law will be followed in the future “for the avoidance of doubt”—because avoidance of doubt is a good thing.

But the Bloomington plan commission has, through its March 14, 2022 gathering, now raised a doubt about the correct interpretation of the 50-percent requirement—when I think there is no legitimate legal doubt.

A good way to eliminate that legal doubt is to ask a judge to settle the matter. That’s why on Monday afternoon, I filed a lawsuit in the Monroe County circuit court. I am representing myself.

[Scan of filed complaint Askins v. Bloomington Plan Commission]

Comments ()