Oral arguments heard in Bloomington’s annexation lawsuit, decision at least a month away

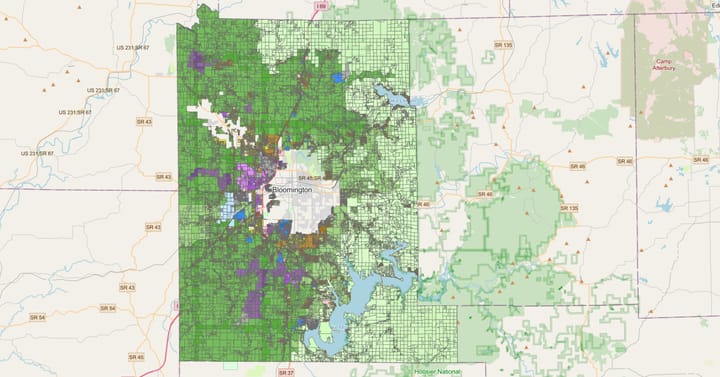

On Friday morning, oral arguments were heard in a constitutional challenge that the city of Bloomington has made to a 2019 state law, which causes annexation waivers to expire after 15 years.

After arguments were presented, which lasted about an hour, judge Nathan Nikirk, did not have any questions for either side. He gave attorneys 30 days to submit their proposed orders in the case.

Nikirk is presiding over the case as a special judge out of Lawrence County, after judge Kelsey Hanlon recused herself.

The 30-day deadline will fall about two weeks ahead of the April 29 start of the annexation trials for two of the areas for which Bloomington’s city council approved annexation ordinances in 2021. That litigation involves separate action, initiated by remonstrators.

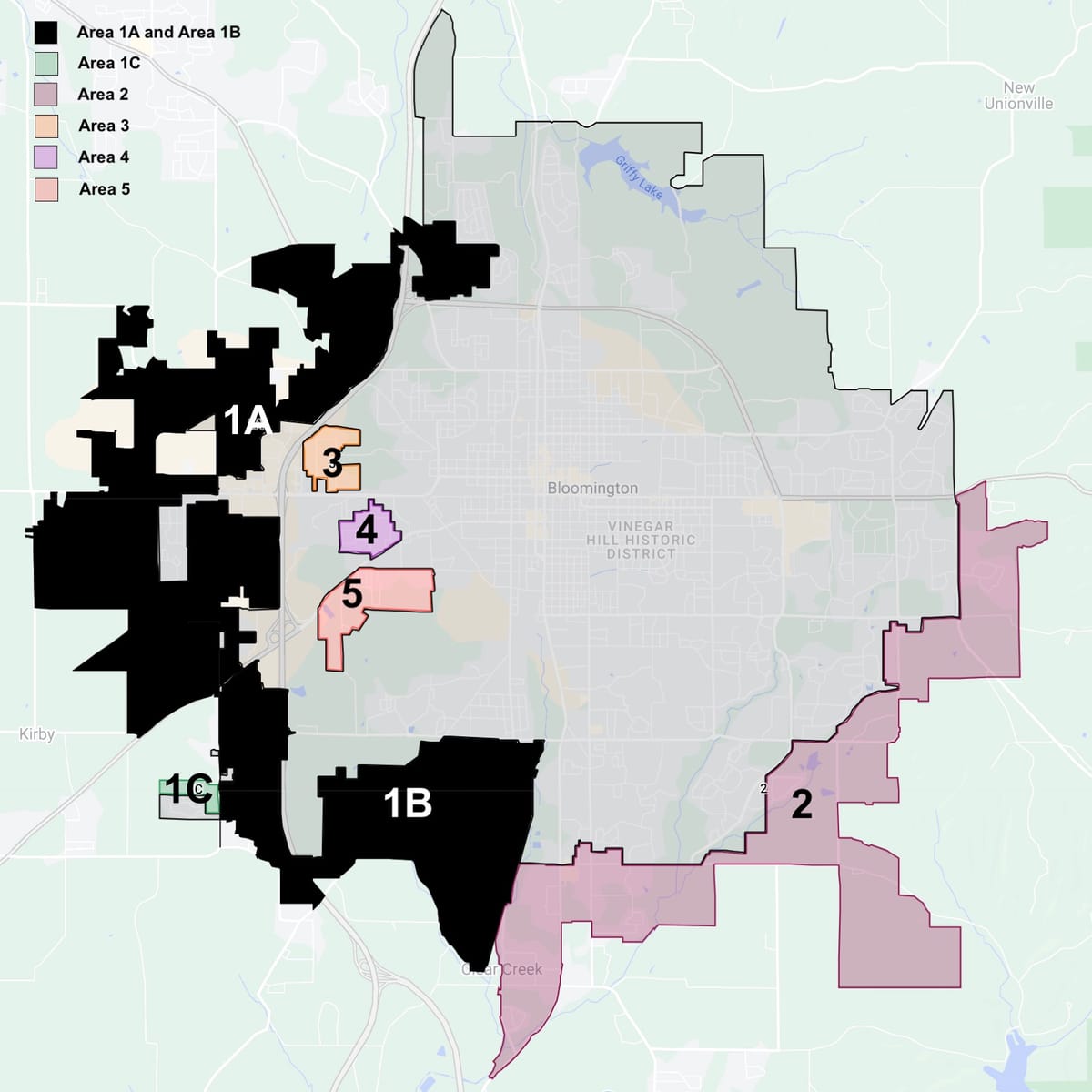

The city’s lawsuits about those two areas (Area 1A and Area 1B) are no longer among the cases that are consolidated under one cause number, and which were heard on Friday.

The city initially filed seven lawsuits, one for each annexation area, but subsequently dismissed the cases involving Area 1A and Area 1B, with prejudice.

Those dismissals, however, still factored into arguments made on Friday.

The named defendant in the litigation for the Friday’s hearing is Cathy Smith, who was Monroe County auditor at the time that remonstrance signatures were counted, and who applied the 2019 law when she made her tally.

Because Bloomington’s lawsuits include a constitutional challenge, it is attorneys from the Indiana attorney general’s office who are representing Smith’s side. On Friday, it was solicitor general James Barta who gave the state’s response to the city’s case. He was accompanied by assistant solicitor general Katelyn Doering.

Presenting first was the city’s lawyer, Andrew McNeil with Bose McKinney & Evans. Also attending on the city’s side were Bose McKinney attorney Stephen Unger, as well as Bloomington’s corporation counsel Margie Rice and city attorney Larry Allen.

McNeil did not use much time addressing the state’s claim preclusion argument. The state’s idea is that the constitutional claims, which the city is now trying to argue, are precluded by the city’s voluntary dismissal of the lawsuits it filed for Area 1A and Area 1B.

For Barta, the claim preclusion argument was a highlight. If the court were to find the argument persuasive, it would not even need to reach the constitutional question on its merits.

The idea of claim preclusion is that in each of the seven lawsuits filed by the city (one for each annexation areas), the constitutional challenge is identical—it includes a facial challenge. By moving to dismiss two of the lawsuits with prejudice, the city was forgoing its chance to make the same constitutional argument in the other cases—so goes the claim preclusion argument.

Judge Kelsey Hanlon, special judge out of Owen County, was presiding over the consolidated cases, when the Area 1A and Area 1B cases were dismissed. Hanlon’s order lists out the remaining five cases and says those five “are not dismissed.”

McNeil argued on Friday that because Hanlon’s order granting the city’s motion for dismissal of the two lawsuits explicitly leaves the other cases in play, consolidated under a single cause number, it was not the intent of the court to preclude the claims based on the constitutional arguments. Responding to McNeil, Barta noted that Hanlon had not explicitly weighed whether the constitutional claims in the other cases would be precluded.

There is still plenty left in the individual remaining consolidated lawsuits, without the constitutional claims. That’s why the arguments on Friday were just about motions for a partial summary judgment.

Bloomington’s complaint for Area 4, for example, includes the allegation that Smith, as auditor, “appears to have counted multiple defective remonstrance petitions that should have been rejected.” For the Area 4 lawsuit, the petitions were specific to Area 4.

Besides the constitutional argument, the remaining consolidated lawsuits have in common an argument the city could still try to make—even if the 2019 law were upheld as constitutional. That argument is based on the idea that the 2019 was passed while Bloomington’s annexations were in progress, but were delayed by a 2017 law passed by the state legislature—a law that was ultimately determined on a 3–2 vote of the Indiana Supreme Court to be unconstitutional.

In the Area 4 complaint, the argument is summarized like this: “Fundamental fairness dictates that Bloomington’s 2017 annexation cannot be scuttled by a 2019 law rendered applicable only due to an unconstitutional delay.”

On the constitutional question, Friday’s oral arguments showed that the issue is more complex than what the words of Indiana’s state constitution or the U.S. Constitution might suggest.

Article I, Section 24 of Indiana’s state constitution reads: “No ex post facto law, or law impairing the obligation of contracts, shall ever be passed.”

And Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution states, “No state shall … pass any … Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts.”

The basic idea, as laid out by McNeil, is that annexation waivers are contracts—between a landowner and the city. In exchange for being allowed to hook up to the city’s sewer system, the landowner gives up the right to remonstrate against annexation.

The 2019 law, by expiring annexation waivers older than 15 years, impairs the obligation of the contract, which makes it unconstitutional—so goes Bloomington’s constitutional argument.

Glossing over several ancillary lines of argument, there is precedent in previous cases that points to the idea that the constitutional prohibition against impairment of contracts is not absolute. On Friday, a case decided by the Indiana Supreme Court in 1991 (Clem v. Christole) was cited several times by both sides, on the question of absoluteness.

The idea is that there can be a tension between the constitutional contracts clause and the general ability of the state legislature to use its “police power” to protect the health, safety or general welfare of the public. In legal disputes about how to resolve that tension, it comes down to whether the health, safety or general welfare of the public is at stake, and whether the legislature’s action is reasonable, given the circumstances.

In the Clem case, the court summed it up like this [emphasis added in bold]:

Our General Assembly is empowered to enact laws in the exercise of the police power of the state. However, simply because a statute is a valid exercise of legislative authority pursuant to such general police power does not necessarily immunize it from our state constitution’s contract clause. Only those statutes which are necessary for the general public and reasonable under the circumstances will withstand the contract clause. It is only this latter necessary police power, rather than the general police power, which provides the exception to the contract clause.

In the case of the 2019 law expiring annexation waivers after 15 years, Barta argued for the state that the legislation was reasonable and narrowly tailored to address the practice of municipalities like Bloomington obtaining waivers and then “sitting on them” without annexing the territory to which the waivers apply—which meant that the 2019 law survived the constitutional test, according to that argument.

On the city’s side, McNeil argued that because the 2019 law is not actually necessary for the protection of health safety and the welfare of the general public, it cannot withstand the contracts clause of the state constitution. Instead, McNeil said, what the 2019 law does is “pick winners and losers.” The law just picks the landowners as winners over the city of Bloomington, McNeil said.

Comments ()