Plan commission lawsuit update: Bloomington makes First Amendment argument against GOP reading of statute

In the ongoing lawsuit over the rightful appointee to Bloomington’s plan commission, Bloomington’s most recent brief has introduced an argument that has not been a part of its previous papers.

The argument is based on the clause of the First Amendment that establishes a right of free association, or non-association.

The lawsuit is now in front of the court of appeals, after Bloomington lost an initial ruling seeking dismissal.

Currently serving on the plan commission since last summer, as the mayor’s appointee, is commercial real estate broker Chris Cockerham.

Litigating the right of Bloomington mayor John Hamilton to make the appointment is Monroe County Republican Party chair William Ellis, who appointed Andrew Guenther, a city environmental commissioner, to the same seat.

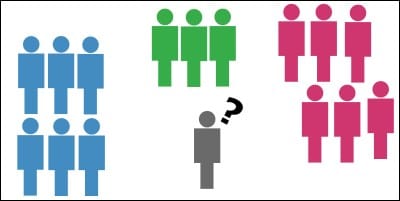

A key question of law in the case involves a state statute that defines what political party affiliation means for a partisan-balanced board like the city plan commission.

The city’s position is that state law allows for someone to serve on a partisan-balanced board, even if they don’t have a party affiliation.

Monroe County Republican Party chair William Ellis, a plaintiff in the case, interprets the law in a different way. Ellis says the effect of the statute is to require someone appointed to a partisan-balanced board to pick a side—they have to have some party affiliation or other.

Lacking a party affiliation was Nick Kappas, who held the disputed seat through 2019, but was not re-appointed at the start of 2020.

Because Kappas had no party affiliation, but was required to have one, Ellis contends, the Republican party affiliation of Kappas’s predecessor decides the question of the appointing authority in favor of Ellis, because the mayor left the seat vacant for more than 90 days.

Bloomington’s new argument is that if Ellis’s interpretation of state law were adopted by the court of appeals, it could potentially open the door to constitutional claims by people who have no party affiliation.

The city’s most recent brief says, “Individual citizens like Kappas, who have a right to not affiliate with a political party, would be categorically denied from appointment to a vast swath of governing boards and commissions for no reason other than their lack of affiliation with an established political party.”

What does the statute in question say?

[A]t the time of an appointment, one (1) of the following must apply to the appointee:

(1) The most recent primary election in Indiana in which the appointee voted was a primary election held by the party with which the appointee claims affiliation.

(2) If the appointee has never voted in a primary election in Indiana, the appointee is certified as a member of that party by the party’s county chair for the county in which the appointee resides.

Bloomington contends that the law is supposed to be used only to decide the question of which party someone belongs to, if they belong to one at all. Bloomington contends that the law does not impose a requirement that someone belong to a party on top of the statute that enables plan commissions.

The statute on plan commissions says a plan commission includes:

Five (5) citizen members, of whom no more than three (3) may be of the same political party, appointed by the city executive.

How vast is the swath of boards and commissions that would be off limits to people with no party affiliation?

Of the city’s more than 40 citizen boards and commissions, four look like they have a partisan balancing requirement: plan commission; board of park commissioners; Bloomington urban enterprise association; and the Bloomington Transit board.

The most recent appointee to the Bloomington Transit board was made by Ellis, even though the city council is the appointing authority.

To make the transit board appointment, Ellis used the same law he cited to attempt the plan commission appointment. Ellis made the appointment to the transit board after the city council failed to make its own appointment within 90 days of the seat becoming vacant.

Ellis’s transit board appointment was local businessman Doug Horn, a Republican. The city council’s appointee, on any interpretation of the statute, could not have been a Democrat.

Both Cockerham and Guenther—the two who lay claim to the plan commission seat—are Republicans under the statutory definition. That’s even though Guenther resigned from the Republican Party at the start of the year.

On the accelerated timeline for the filing of briefs, which the court of appeals has approved for the case, Ellis and Guenther have to submit their response to the city’s brief by the first week of February.

Comments ()