Private letter from Bloomington city council to mayor influenced proposed 2024 budget

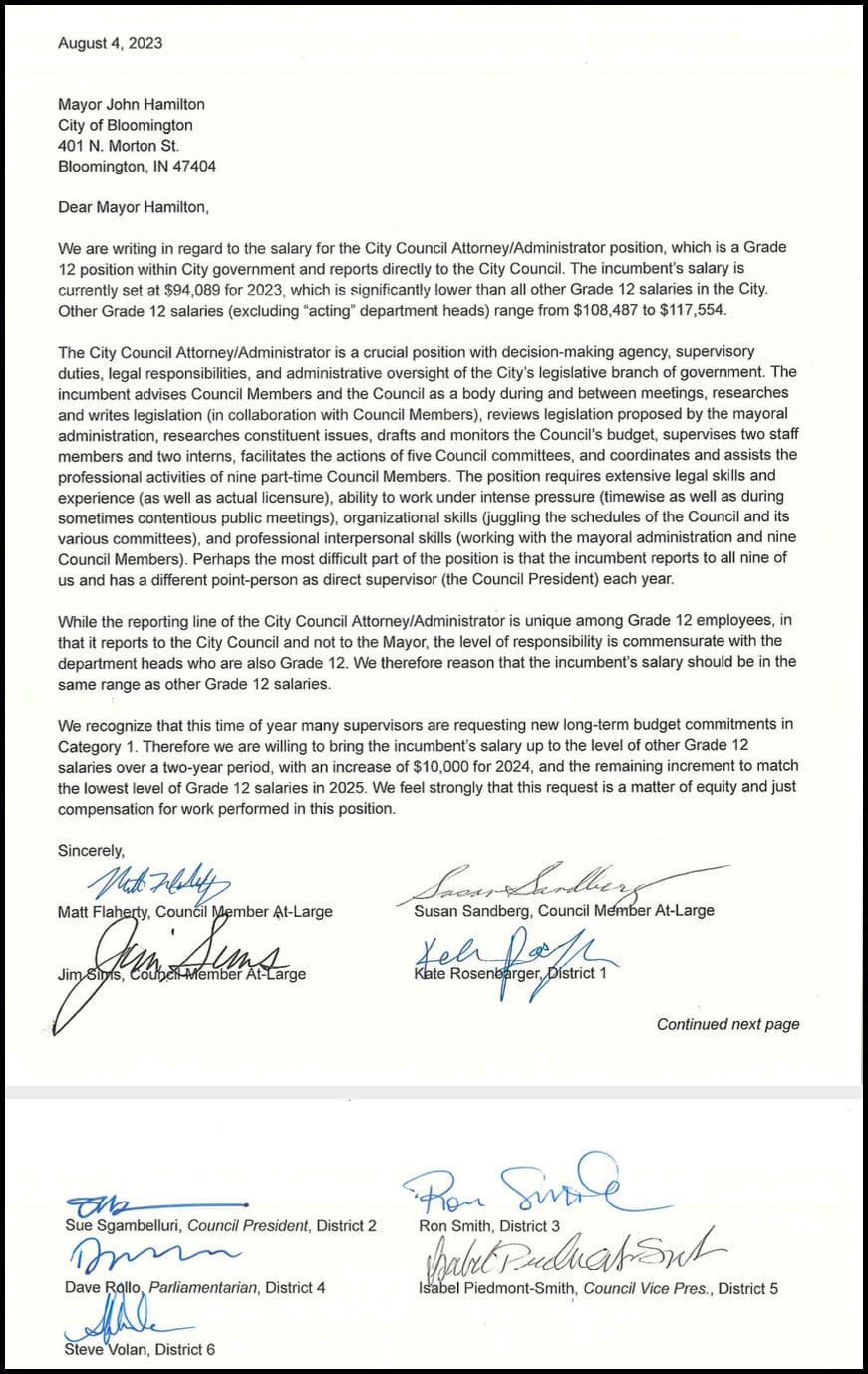

A response on Thursday to a records request made by The B Square a month earlier, shows that Bloomington’s 2024 proposed budget was influenced by a private letter to Bloomington mayor John Hamilton, with apparent wet signatures from all nine city council members.

The letter asked that the mayor increase the pay for the city council’s administrator/attorney from a 2023 salary of $94,089 to $104,089 in 2024. That’s a 10.6-percent increase, or more than twice the 5-percent increase called for in the mayor’s proposed budget for all other non-union employees.

The city council’s argument is based on the idea that the city council’s administrator/attorney should be paid on par with the director of city of Bloomington utilities, the police chief, the fire chief, the head of public works, and the city’s corporation counsel, among other positions described as “department heads” in the city’s employee manual.

The letter also asks that the council’s administrator/attorney position receive another additional significant increase in 2025.

But any increases to the council staff salary budget for 2025 would depend on the decision by the next mayor, which is almost certain to be Democratic Party nominee Kerry Thomson. She’s unopposed on the Nov. 7 ballot. In general terms, under state law, the city council can reduce but not increase the mayor’s proposed budget amounts.

Before the city council’s Aug. 28 departmental budget hearing, there was no discussion by councilmembers at public meetings leading up to that hearing, about their desire that the administrator/attorney receive a substantial pay raise in 2024, beyond the standard cost-of-living increase for all employees.

The first mention of the council’s interest in paying their own administrator/attorney on par with the city’s department heads came at the Aug. 28 hearing, when the bigger pay raise had already been incorporated into the mayor’s proposed budget.

Councilmember Matt Flaherty said at the hearing that he wanted to “thank and recognize the mayor, for addressing an increase in council attorney Lucas’s proposed salary…as requested by the council.” The council’s administration/attorney, Stephen Lucas had earlier in the meeting told the council that his job had been given a 10.6-percent increase—at the request of councilmembers.

Lucas was hired by the current edition of the city council in 2020 after serving for about nine months as deputy under long-time council administrator/attorney Dan Sherman. The council opted not to conduct a search for the position, or to subject Lucas to any formal interview process.

The council at first tried to shield from public view the information it used to reach their decision on hiring Lucas and his compensation. But after Indiana’s public access counselor sided with The B Square’s position, the council released a previously redacted email message.

Based on the information in the 387-page budget book that the administration had released the Friday before the Aug. 28 hearing, it was not possible to discern that the city council’s administration/attorney position had received a significant pay bump in the 2024 budget.

The $10,000 increase for the council’s administration/attorney is not mentioned in the narrative of the 2024 budget book. It’s not possible to derive the fact of an increase beyond the standard 5-percnt bump from the budget book’s numbers for the city council office. In the budget book, the standard 5-percent raise had, erroneously, not been applied to city councilmember salaries—that’s according to remarks made by Lucas at the Aug. 28 hearing.

The date of the Aug. 28 hearing was six days after The B Square had made a request under Indiana’s Access to Public Records Act for (emphasis added) “any letters signed by members of the Bloomington city council and sent to mayor John Hamilton between Aug. 1, and Aug. 21, on topics related to the 2024 budget, including departmental budgets, including the council’s own office budget, as well as compensation for staff.”

The city’s initial response to The B Square’s request did not come until Sept. 1—but the document produced by the city was an unsigned letter.

The B Square immediately followed up, pointing out to the city’s legal department that the unsigned letter was not responsive to the request for signed letters, and made a new request, again stating explicitly that the request was for signed letters, not unsigned letters.

On Sept. 21, three weeks after the new request, the city produced to The B Square the letter with apparent wet signatures from all nine council members. A day later, on Sept. 22, the signed letter was included in the city council’s posted Sept. 27 meeting information packet, which contained budget questions from councilmembers and answers from city staff.

The B Square’s new request, made on Sept. 1, included email messages that had been used to convey the signed letter to the mayor as an attachment.

In response, the city also produced an email message from Isabel Piedmont-Smith to the mayor, which conveyed what was apparently an unsigned version of the letter. There are three reasons that point to the attachment being an unsigned letter. First, Piedmont-Smith describes the attachment as “approved unanimously by all 9 Council Members” as opposed to “signed by all councilmembers.”

Next, the indicated file size of the attachment is just 44 KB, which is substantially smaller than the 434 KB for the .pdf file containing just the signed letter.

And finally, Hamilton’s response to Piedmont-Smith is a request for a document that is signed, which would not have been necessary if the attachment were already signed. Hamilton’s response to Piedmont-Smith’s email message was: “Do you think for the record we could get a signed document with all (or at least 5) councilmembers having signed it? That would be helpful from my perspective.”

Hamilton’s reply is heavily redacted. The .pdf file that contains the email exchange includes a redaction log that states “no reason” as the reason for the redaction. Elsewhere in the city’s NextRequest software platform, which Bloomington uses to respond to records requests, there is a statement reading: “Records that are advisory or deliberative have been withheld in accordance with Indiana Code 5-14-3-4(b)(6).”

Based on previous opinions issued by Indiana’s public access counselor, the fact of a letter signed by all nine councilmembers would not necessarily entail a violation of Indiana’s Open Door Law (ODL).

Indiana’s public access counselor, Luke Britt, has previously considered similar situations. One involved a 2013 complaint against the Indiana State Board of Education. Britt’s reasoning in that case was that a sequence of electronic communications among members, agreeing on the content of a letter to be signed, would not necessarily amount to a violation of Indiana’s ODL, because such communications were not “simultaneous.”

About the emailed communications involved in the 2013 complaint, Britt wrote: “This is not ‘simultaneous’ therefore, must be treated akin to a serial meeting.” The Indiana ODL prohibits serial meetings, which are a sequence of meetings where at least three members meet, and within a week of that three-person meeting, there are additional meetings of at least two members on the same topic, such that the sum of members involved is more than a quorum.

But even considering the possibility of a serial meeting, Britt wrote, “Indiana law has not yet addressed whether a meeting of the minds over an email chain would constitute constructive presence for public meetings or in an aggregate sum.” In the 2013 opinion, Britt encourages the state legislature to look into the matter.

Britt concluded that opinion with the following statement:

I encourage all public agencies to be especially attentive to the purpose of public access laws to avoid ambiguous situations and arousing suspicions of prohibited activities. Regardless of intent, the appearance of action taken which is hidden from public view is particularly damaging to the integrity of a public agency and contrary to the purposes of transparency and open access.

Comments ()