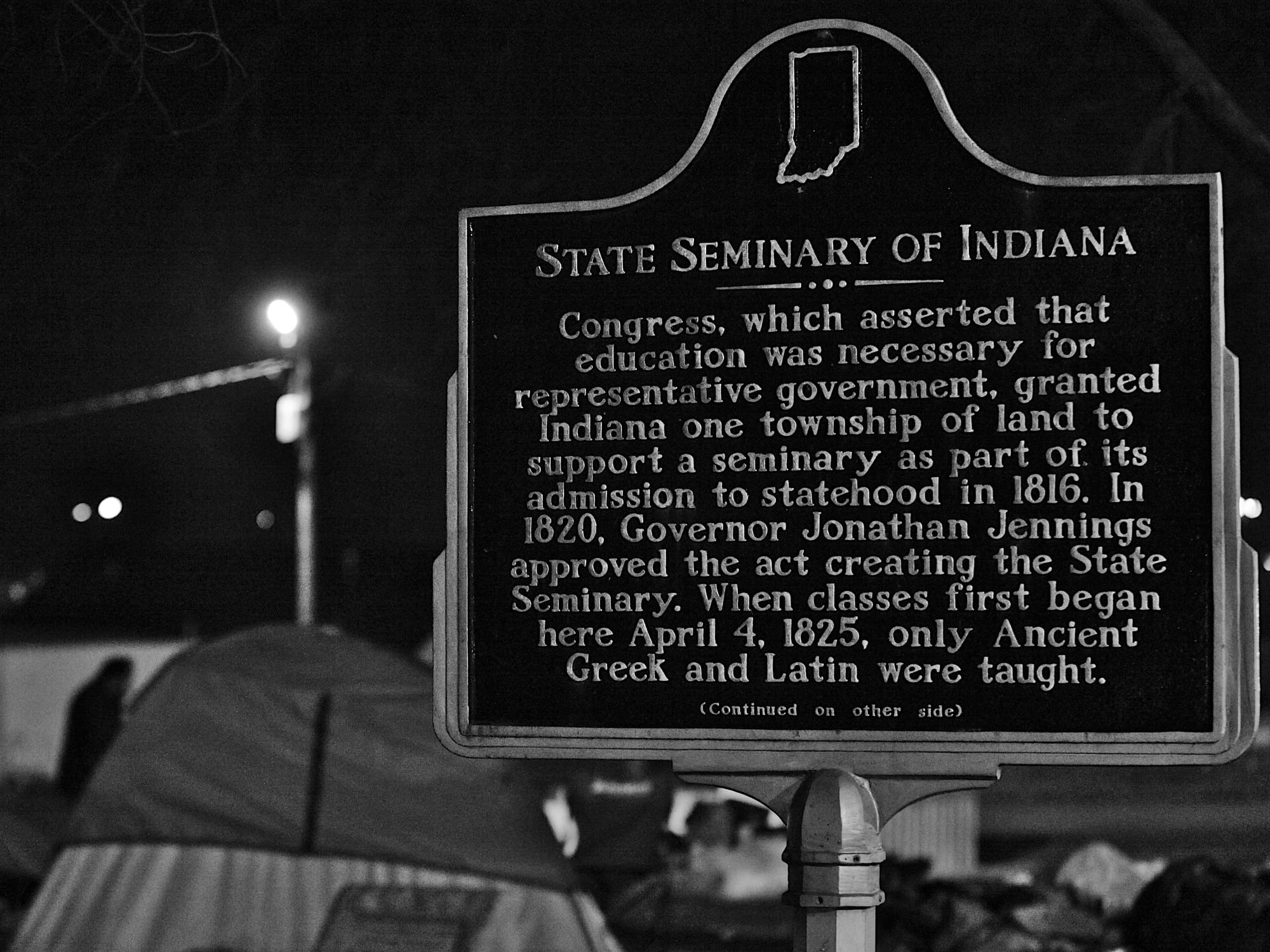

Removal of people, personal property from Bloomington’s Seminary Park prompts question: What, if anything, is an encampment?

When it was founded in 1825, the school that stood on what’s now a park, at 2nd and Walnut streets in Bloomington, taught just two subjects, both heavy with vocabulary study—Greek and Latin.

What’s the right word to describe Seminary Park over the last few weeks?

It was at least a community of people.

They spent the day socializing around tents and stacks of belongings draped in tarps. For most of them, that meant garden-variety small talk, about the weather, gossip, or other mild pursuits. For a few, it meant a transaction for illicit substances. For a couple, it included brawling on the ground, getting in as many punches as they could, before getting separated by a recognized peacemaker in the group.

Several complaints are logged in the city’s uReport system about camping in Seminary and Switchyard parks.

What had become increasingly visible over the last few weeks is no longer there.

On Wednesday night, Seminary Park was the site of action taken in a coordinated effort between Bloomington police department’s downtown resource officers, its social worker, and staff from two area nonprofits, Centerstone and Wheeler Mission.

Towards 11 p.m., people in the park were approached by police and nonprofit staffers and told they would not be able to stay—that’s when official park hours end. Centerstone staffers called people by name, when they approached, and they seemed familiar to park community members.

A Bloomington Transit bus was on hand to drive what turned out to be one passenger to the Wheeler Mission shelter. Three other park community members agreed to take rides they were offered to the Stride Center. That’s a crisis diversion program that opened in late August on the lower level of Monroe County’s Morton Street Parking garage.

Centerstone administrative director, Greg May, told the B Square Beacon (BSB), he thinks the relationships that his street outreach staff had established with people in the park community over time had helped convince them to go to places like Wheeler Mission’s shelter and the Stride Center.

The dozen or so other people who were in the park drifted away to an unknown place somewhere else.

After that, BPD patrol officers and evidence technicians arrived and took pictures of the tents, tarps and other scattered items, so that their location in the park was documented. They started loading the property into trucks and trailers that had been deployed on the College Avenue side of the park. According to police chief Mike Diekhoff, the property was transported to a parks and recreation facility where it could eventually be claimed by its owners.

For public commenters at a board of park advisory commissioners on Tuesday night, the right word to describe the community at Seminary Park was “encampment.”

That means it was subject to Centers for Disease Control COVID-19 pandemic guidelines, which say, “If individual housing options are not available, allow people who are living unsheltered or in encampments to remain where they are.”

The CDC pandemic guidelines appeared to help persuade park commissioners to vote 1–3 on a proposed revision to park policy that would have expanded an overnight no-camping rule so that it applied at any time. When park commissioners voted down the policy change, many observers concluded the city would allow the Seminary Park community to stay for at least a while longer.

Bloomington’s mayor John Hamilton disagrees that Seminary Park was an encampment.

Hamilton told The B Square Beacon (BSB), “We take the CDC recommendations and guidance on this very seriously. I think what I would say about this is, number one, this was not an encampment—this was not where people lived.”

Hamilton continued, “They were not generally sleeping overnight at the park and that’s been the rule and the expectation.” He added, “I can’t say that that has never happened—from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m. or from 3 a.m to 5 a.m. or various times.”

On Wednesday night, at least one of the people staying at the park, who preferred not to be named, seemed to be calling the park home.

Anon park dweller: I wish they got like a crane or something to help us move.

BSB: Do you have a place to go?

Anon park dweller: Yeah, I got a tent right there. [points]

BSB: But I mean, they’re not gonna let you stay there.

Anon park dweller: Yeah, I know.

BSB: So you got a place you can go after this?

Anon park dweller: I’ll just move locations, you know.

Forrest Gilmore, executive director of Beacon (formerly the Shalom Community Center) told the BSB, “People are sleeping in the parks, all over the city. The idea that they are not is silly. Of course they’re sleeping in the parks.”

Gilmore said that in contrast to Wheeler Mission and Centerstone, Beacon was not told by the city of Bloomington in advance of Wednesday night’s planned removal of people and property from the park.

Some of the people who were part of the Seminary Park community did not have the option to relocate to a shelter, because they’re suspended or permanently banned.

Centerstone’s Greg May told the BSB that one woman who agreed to go to the Stride Center on Wednesday was under a three-month suspension from the Friend’s Place shelter, operated by Beacon.

Gilmore said couldn’t speak to the individual situation, but confirmed that sometimes people do get suspended or on rare occasions permanently banned from the shelter. The reason for a suspension or a ban is usually violence, towards staff or another resident of the shelter, Gilmore said.

Beverly Calender-Anderson, who’s director of community and family resources for the city of Bloomington, told the BSB a lot of people experiencing homelessness don’t understand the difference between a suspension and a ban.

Calender-Anderson, who works with nonprofits like Wheeler Mission, said a suspension from staying overnight at the Wheeler shelter doesn’t necessarily mean a ban during the day. Outreach workers might know of two or three people in the park who eventually can come back once their suspension is over. So they try to make them aware when they’re allowed to return to the shelter.

In her remarks during Tuesday’s board of park commissioners meeting, Calender-Andersen said, “We need to come together…as well as a community and figure out: How do we solve the underlying issues, so that people won’t need to be in the park?”

In Gilmore’s view, shelter capacity is not the problem. The problem is a lack of housing. “The biggest gap in housing in the city is places from zero to $400 rent a month,” Gilmore said.

“Instead of taking a shelter-first approach, we should take a housing-first approach,” Gilmore said. He added, “The idea that people need to spend time in a shelter before they’re ready to be housed, is outdated.”

Part of the solution being pursued by Bloomington and Monroe County government, which is neither shelter nor housing, is the Stride Center, a crisis diversion center which opened in late August this year.

According to May, in the roughly three months since it opened, 85 people have been referred to the Stride Center. A referral has to come from law enforcement or IU Health, which means either in-patient or out-patient behavioral health or the emergency department.

Those 85 different people have amounted to 240 total visits, according to May.

A program that’s meant to address underlying problems started about four years ago, according to May, around the time communities of people experiencing homelessness started establishing themselves at People’s Park on Kirkwood Avenue downtown.

Through the program, those experiencing homelessness are hired as employees of Centerstone, which contracts with the city to do work for the parks and recreation department in the summer and public works in other months. Some of the work includes maintenance at Cascades Golf Course, invasive plant species removal on city properties, and park cleanup. Public works labor includes painting curbs and clearing snow from handicap access ramps in the winter.

Some of the employees are reluctant to do the cleanup work in parks that have been occupied by a homeless community, because of the unsanitary conditions and the number of syringes and drugs that are being found there, May said. For the employees who are in recovery from substance abuse, it’s a challenge to their sobriety.

Another city-coordinated program, which builds on the Centerstone employment program, was piloted this fall as a way to try to engage park communities. The Public Health in the Parks program was approved by the board of park commissioners in early September.

The program, which ran from September through November, tried to establish a presence in some of Bloomington’s parks through a street outreach staffer from Centerstone. The staffer was supposed to help monitor activity in the park, with an eye towards connecting people, including those without permanent housing, with services they need.

A popup tent was set up as a distribution point for disposable masks and gloves, sanitizing products, winter accessories, and snacks. Included in the program were: Seminary, Switchyard, Butler and Building Trades parks.

The vote by the board of park commissioners on Tuesday, against the proposed policy change for daytime use of the parks, led many to conclude that meant no action would be taken to remove the park communities at least a while longer.

Didn’t that vote mean the park campers would be left alone?

Mayor Hamilton responded to that question from the BSB by saying, “We don’t ‘leave them alone.’ We engage them—through programs like Public Health in the Parks.”

The mayor’s office posted a statement about the Wednesday night action late Thursday afternoon. Included in the statement was part of the reason for the city’s decision to enforce the overnight camping prohibition: “Sleeping outdoors does not provide protection from the elements, or adequate access to hygiene and sanitation facilities.”

Hamilton told the BSB that the decision for action on Wednesday night was based on a recommendation from the administration’s leadership, which included deputy mayor Mick Renneisen, parks and recreation director Paula McDevitt, director of public engagement Mary Catherine Carmichael, director of community and family resources Beverly Calender-Anderson, police chief Mike Diekhoff, among others. Hamilton said after review and discussion, he had approved the recommendation.

The daytime high temperature on Thursday was around 63 F degrees with a forecasted high of 59 F on Friday—relatively mild for early December. But starting Saturday, the overnight low is forecast to be consistently below freezing.

Responding to a question from the BSB, Hamilton said weather was not a factor in the decision for action on Wednesday.

Online commentary by advocates for the homeless community has condemned the city’s Wednesday action.

A “Hands off the Homeless” rally, sponsored by the Homeless Coalition is set for 5 p.m. on Friday at the Monroe County courthouse.

Comments ()