Ridership decline in 2025 for Bloomington Transit, board weighs ridership targets

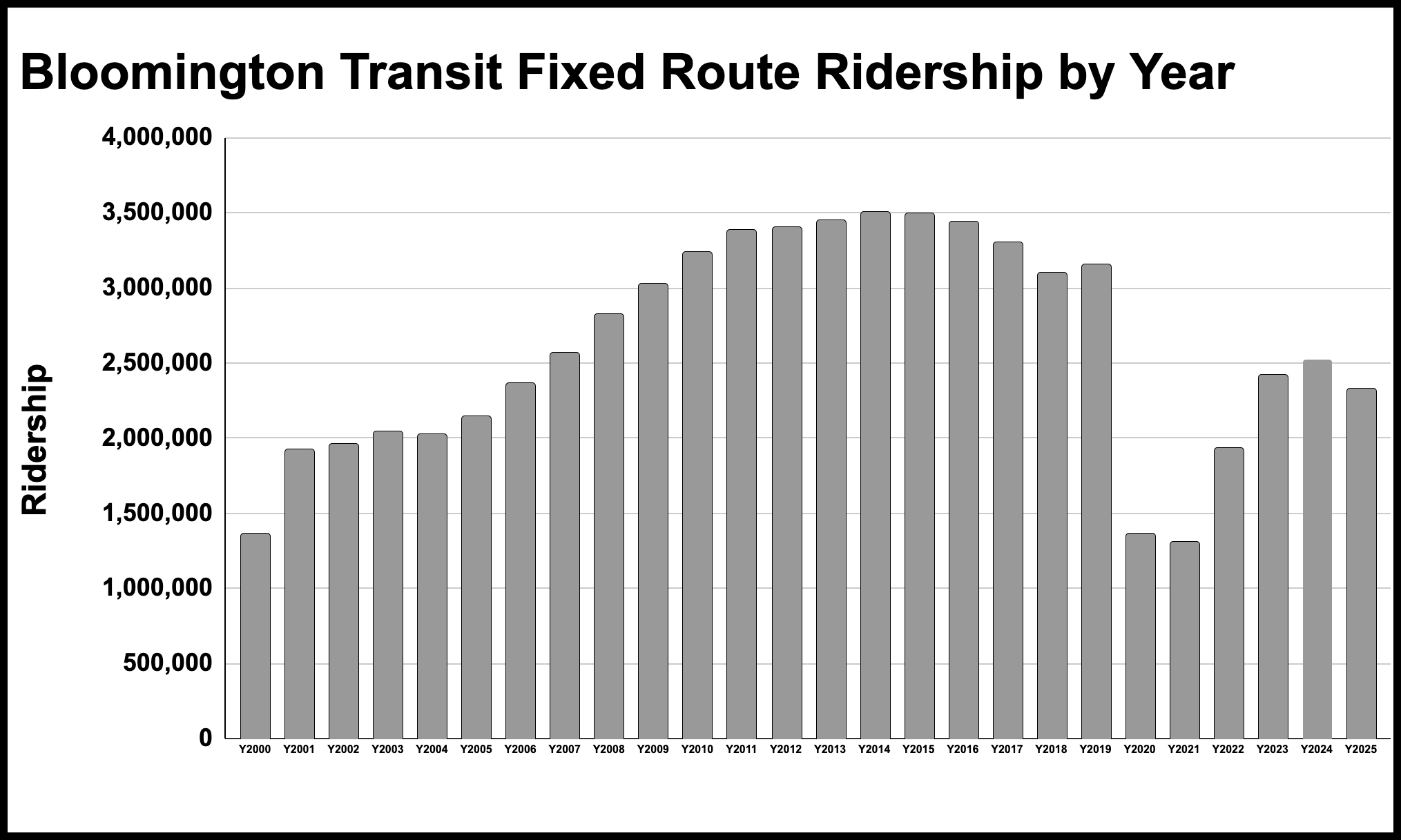

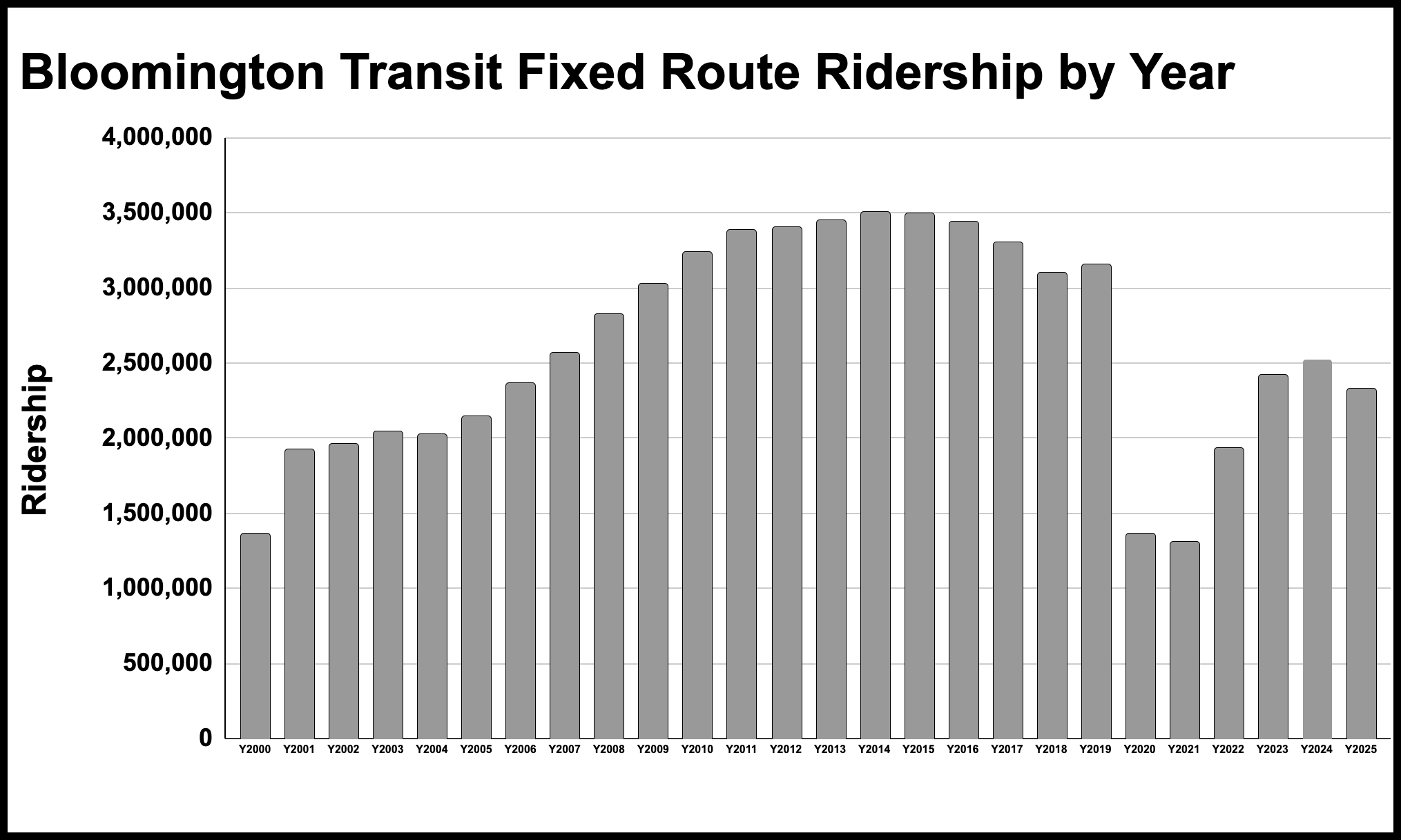

Bloomington Transit’s board reviewed key performance indicators Tuesday as total ridership fell from about 2.5 million trips in 2024 to 2.3 million in 2025. Members questioned whether changes in counting and fare enforcement affected results and asked staff to return with 2026 targets.

Bloomington Transit’s five-member board spent about an hour of its Tuesday (Jan. 20) meeting talking about how to set and interpret key performance indicators (KPIs), especially those tied to ridership, as BT wrapped up 2025 with a year with an overall decline in passenger numbers.

BT’s fixed-route ridership has not come close to rebounding to pre-pandemic levels. After a few years of a clear recovery trend, 2025 was the first year when BT lost ground.

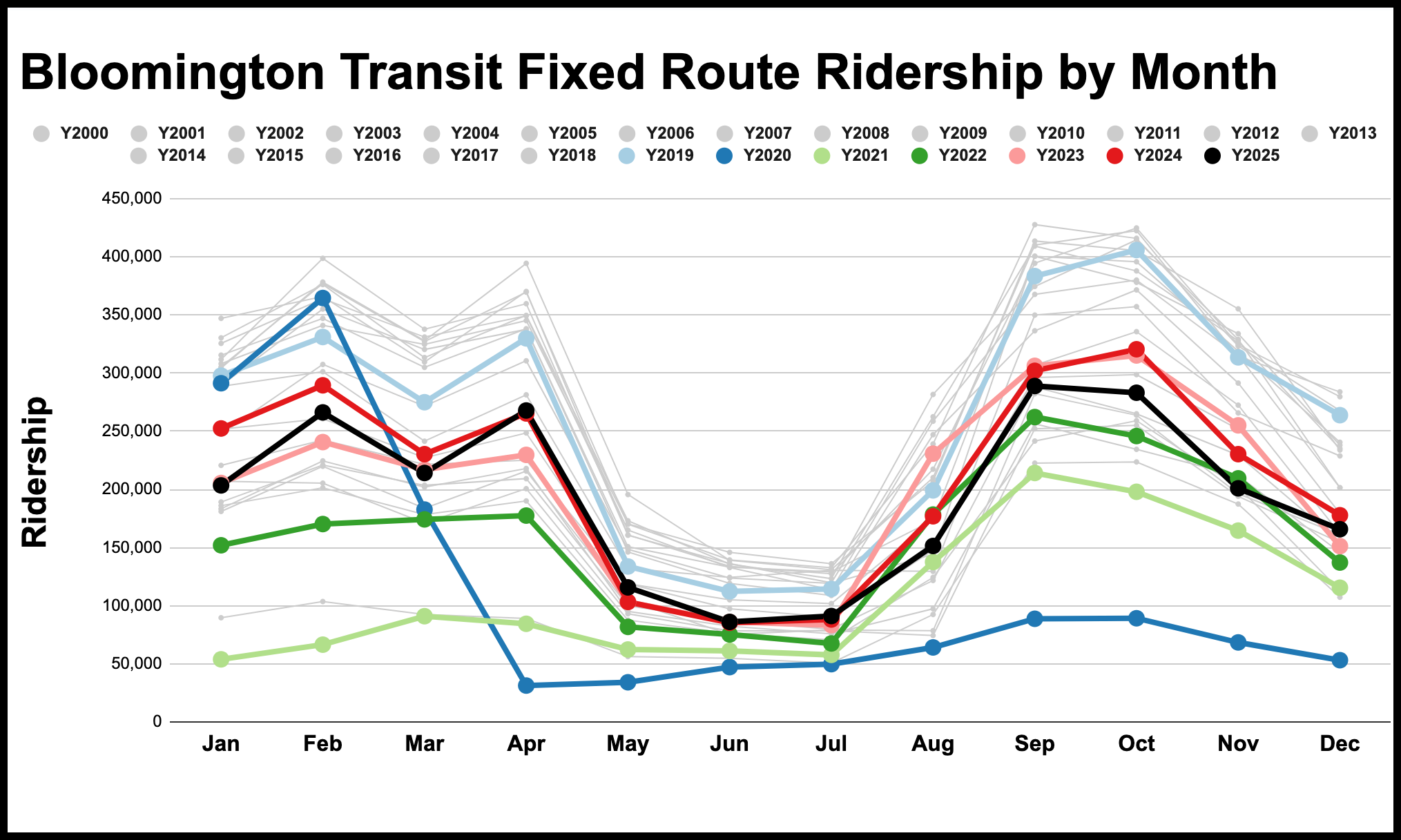

According to Bryan Fyalkowski, BT’s manager of marketing and development, total ridership—across fixed-route service, BT Access (paratransit), and BLink (on-demand microtransit)—fell from about 2.5 million in 2024 to 2.3 million in 2025—a drop of roughly 190,000 trips. Fourth-quarter ridership alone was down about 80,000 trips year-over-year. Fyalkowski told board members almost every month in 2025 showed a decrease, with notable losses on IU campus routes like Route 6 and Route 9 in December.

Pre-pandemic figures for fixed-route ridership were better than 3 million rides a year.

General manager John Connell attributed some of that decline to stricter fare enforcement made possible by new electronic validators and the elimination of paper transfers, which he said had allowed “a significant level of fare evasion.” With the validators in place, Connell said, people who were “beating the system and riding more often because they could” have largely been forced either to pay or to stop riding.

Another source of ridership loss could be the shift from passengers to the Indiana University buses, especially after BT stopped serving IU’s Tulip Tree housing complex on 10th Street. There are now no remaining fixed routes that go under the 10th Street railroad bridge—because the new battery electric buses that have been added to BT’s fleet won’t fit under it.

Actual passenger counts now come from automated passenger counters (APCs), not from farebox scans combined with manual button presses by drivers to count boarding passengers. BT’s special projects manager Shelley Strimaitis told the board that APCs had been benchmarked against manual counts for a couple of years and met accuracy standards.

Board member Doug Horn pressed for better documentation of those methodological changes, so that ridership charts don’t invite easy misinterpretation: “It may not necessarily be that we’re losing ridership, it’s just that we’re counting better.”

Ridership goals

For 2025, the board had set a 2.5 percent ridership increase as its goal. Fyalkowski recommended keeping that same target—2.5 percent growth over the 2025 actual total—for 2026.

When the board took up the question of what the targets should be, Don Griffin asked staff to ground the goals in their own professional judgment: “You know what you’re doing,” Griffin told them, adding, “Come back and tell us what you think those numbers should be.”

Board chair James McLary pushed for “stretch goals” rather than what he called “comfortable” targets, especially in light of a planned marketing effort budgeted at up to $100,000. If Bloomington Transit is going to spend that kind of money, he said, “I would hope that we could get another 2% out of that.”

Horn framed the issue in terms of accountability: “Goals need to be tied to action,” he said Connell responded by saying that each KPI is already linked to concrete internal steps—citing preventable accidents as an example—where Bloomington Transit has invested in telematics, training, and an outside safety assessment. He suggested a board work session if members wanted to “get into the weeds” on each indicator.

In the end, at the suggestion of Fyalkowski, the board asked staff to bring back a refined set of recommended KPI targets for 2026 at their next meeting, rather than voting on changes at their Tuesday meeting.

Productivity metrics for fixed routes showed that passengers per revenue mile and per revenue hour generally met or exceeded internal 2025 goals, but were still below 2024 levels.

For BLink, the on-demand micro-transit service, Fyalkowski reported that passengers per revenue hour came in at about 2.53, well above the target of 2.0. That prompted McLary to question whether some goals were now too low to be meaningful: “If you have a goal that you are exceeding, then your objective should be to stretch that goal.” He added, “If you’ve got a goal of 2, and you do 2.53, why have a goal of 2?”

For 2025, on-time performance for fixed routes hovered around 70% to 75%. Strimaitis said that for larger transit systems, 50% to 70% on-time performance is fairly common. She suggested resetting Bloomington’s goal to something closer to 75%, perhaps combined with a route-level floor—for example, no single route below 60%.

Connell added that from a rider’s point of view, the critical question is usually whether they make their downtown transfer on time, saying that “schedule adherence” at intermediate timepoints can look poor, even when customers are satisfied.

One particular fixed route was a source of grave concern for McLary, Route 13, which is the new Ivy Tech route. “The only question is the Ivy Tech route, which is, I mean, it’s ugly,” he said. By the actual numbers, Route 13 in December had 2.78 passengers per hour, which was dead last among all routes, with the next-worst Route 4 (West Bloomfield Rd) coming in at 7.04 passengers per hour. Systemwide, the average of all routes for 2025 was 25.19 passengers per hour.

Strimaitis told McLary there’s a consensus among staff that Route 13 “can’t be left the way it is,” and said options being weighed include redesigning the route or switching to different kinds of service. A partially built apartment complex on the corridor could eventually boost demand, she said.

After the meeting, responding to a B Square question, Strimaitis said she knows there are some riders who have come to rely on the Route 13 service since it was introduced at the start of the year, and that she does not want to just eliminate the route based on a statistic, without thinking it through.

What does “farebox revenue” mean?

The KPI labeled “farebox revenue” prompted a definitional discussion. Controller Christa Brown explained that Bloomington Transit’s financial systems roll together cash fares, pass sales, and pre-paid contracts (such as the agreements between BT and Indiana University and apartment complexes) under fare revenue.

McLary pushed back, saying he wanted to see a breakdown that separates truly on-bus collections and passes from contract revenue: “From my perspective, passes [are] farebox revenue, but contract revenue is not really farebox.” Brown said the kind of report McLary wants already exists in BT’s internal financials and can be presented in whatever format the board prefers.

Having a handle on farebox revenue is important, because it feeds into the farebox recovery ratio, which is the amount of the agency’s operating expenses that are covered by passenger fares. BT’s farebox recovery ratio for fixed-route buses has historically been around 20% or better, which is relatively high compared to other transit agencies across the country.

Comments ()