Some Indiana counties with urban hubs should still not feed birds, mystery of deaths not solved

New advice to bird lovers was given early Monday afternoon on the updated webpage about mysterious songbird deaths, created by Indiana’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

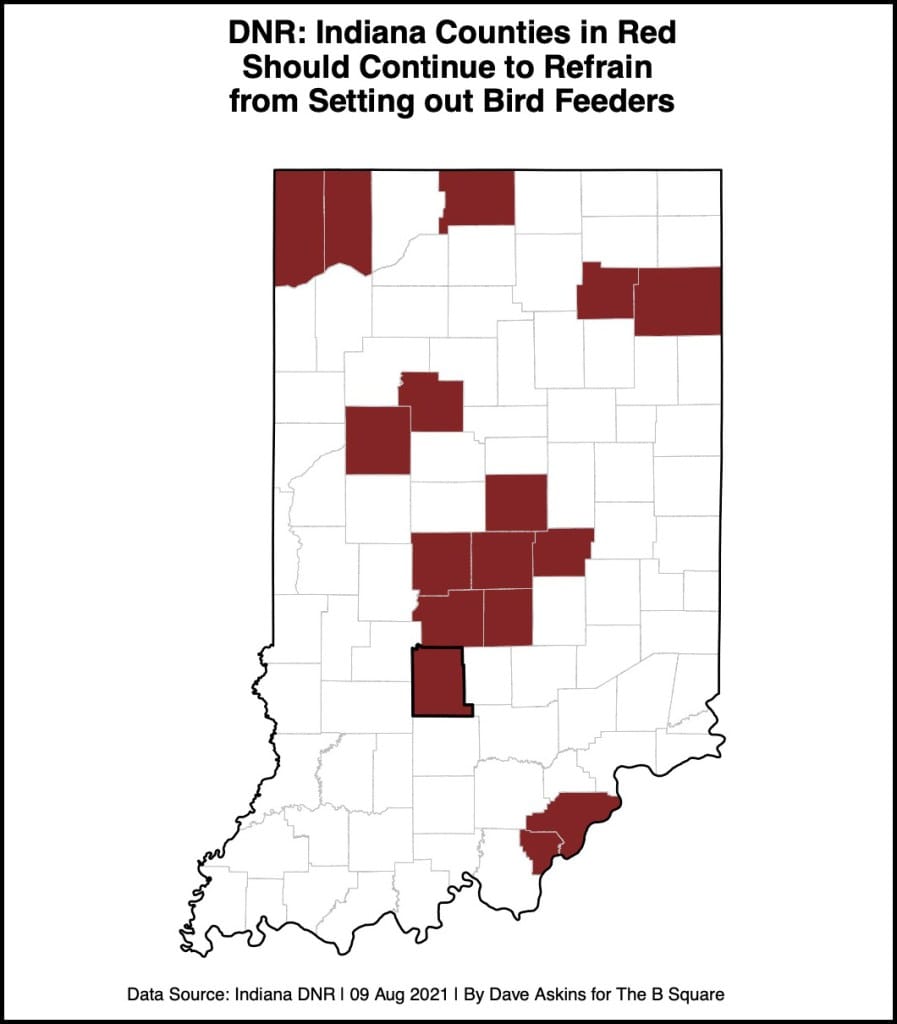

People in 16 Indiana counties should continue to refrain from feeding birds, in order to reduce the chance of promoting a pattern of dead and dying birds.

The pattern was first noticed in late June. It could be caused by a pathogen that is spread from bird to bird, but that’s still not known.

The DNR’s previous advice against feeding birds applied statewide.

The malady involves eye swelling and crusty discharge, as well as neurological signs. Similar reports have come from Washington D.C., Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, according to the US Geological survey.

Affected species include: American robin, blue jay, brown-headed cowbird, common grackle, European starling, various species of sparrows and finches, and northern cardinal.

The DNR is advising against feeding of birds in just some areas the state. According to the DNR website, “Based on the data, it appears that the bird illness is consistently affecting specific areas.”

The 16 Indiana counties where vigilance is still encouraged have something in common: They include urban centers. The possible connection between urban centers and the malady is also not clear.

The feeding of birds is still discouraged in the following 16 Indiana counties: Allen, Carroll, Clark, Floyd, Hamilton, Hancock, Hendricks, Johnson, Lake, Marion, Monroe, Morgan, Porter, St. Joseph, Tippecanoe, and Whitley.

The updated website indicates that 500 possible cases in 72 Indiana counties involved the hallmark set of clinical signs—crusty eyes, eye discharge, and/or neurological issues. That’s about 15 percent of the more than 3,400 reports of sick or dead birds that were filed with the DNR.

Amy Kearns, who’s assistant ornithologist with the Indiana Division of Fish & Wildlife, told The B Square that in other counties, people should clean their feeders before setting them back out.

Proper cleaning means using hot, soapy water to scrub all the organic debris off, followed by a soak in 10-percent bleach solution, and then a very thorough rinsing and drying, before the feeders are refilled with birdseed, Kearns said.

For the listed 16 counties where feeding is still discouraged, spreading birdseed on the ground is not a viable option, Kearns said. It’s the congregating of the birds that is undesirable.

“There’s still a lot we don’t know about this disease we don’t know, even if it’s contagious,” Kearns said. But working on “an abundance of caution,” if the close proximity of one bird to another bird could potentially spread the disease, it’s important to make sure that the disease is not being spread inadvertently, she said.

Especially during the summer months, Kearns said, birds don’t need the food provided in bird feeders. “We do that for our own enjoyment,” she added.

The possibility that the malady is caused by a toxin has not been ruled out, Kearns told The B Square.

What has been ruled out are common bird diseases like avian influenza and West Nile virus, according to the updated website. The cause and transmission of the disease outbreak is currently unknown.

The website indicates: “There is no imminent threat to people, the population of specific bird species, or to the overall population of birds in Indiana.”

Comments ()