‘Stadium District’ sidelined: Bloomington council votes 7–1 to nix naming plan for now

Bloomington’s city council voted 7–1 on Wednesday to postpone indefinitely a proposal to name the area around Miller-Showers Park the “Stadium District.” Neighbors objected to the branding effort, saying it ignored residents and would amplify unwanted “stadium culture.”

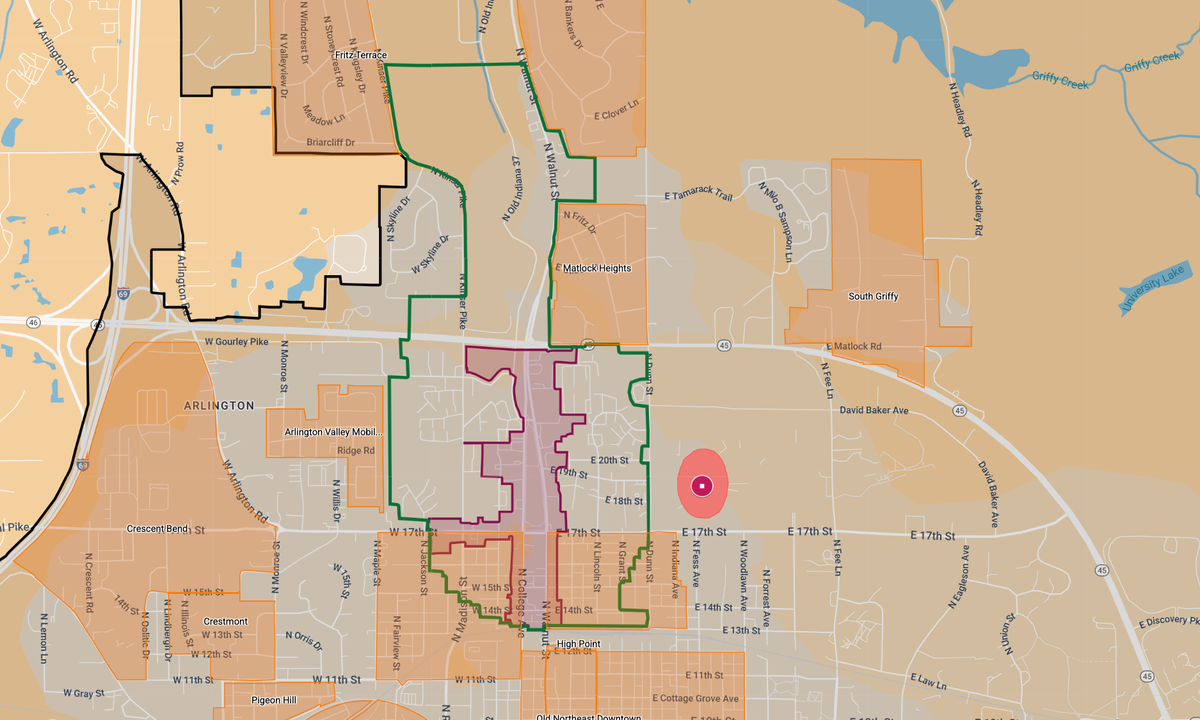

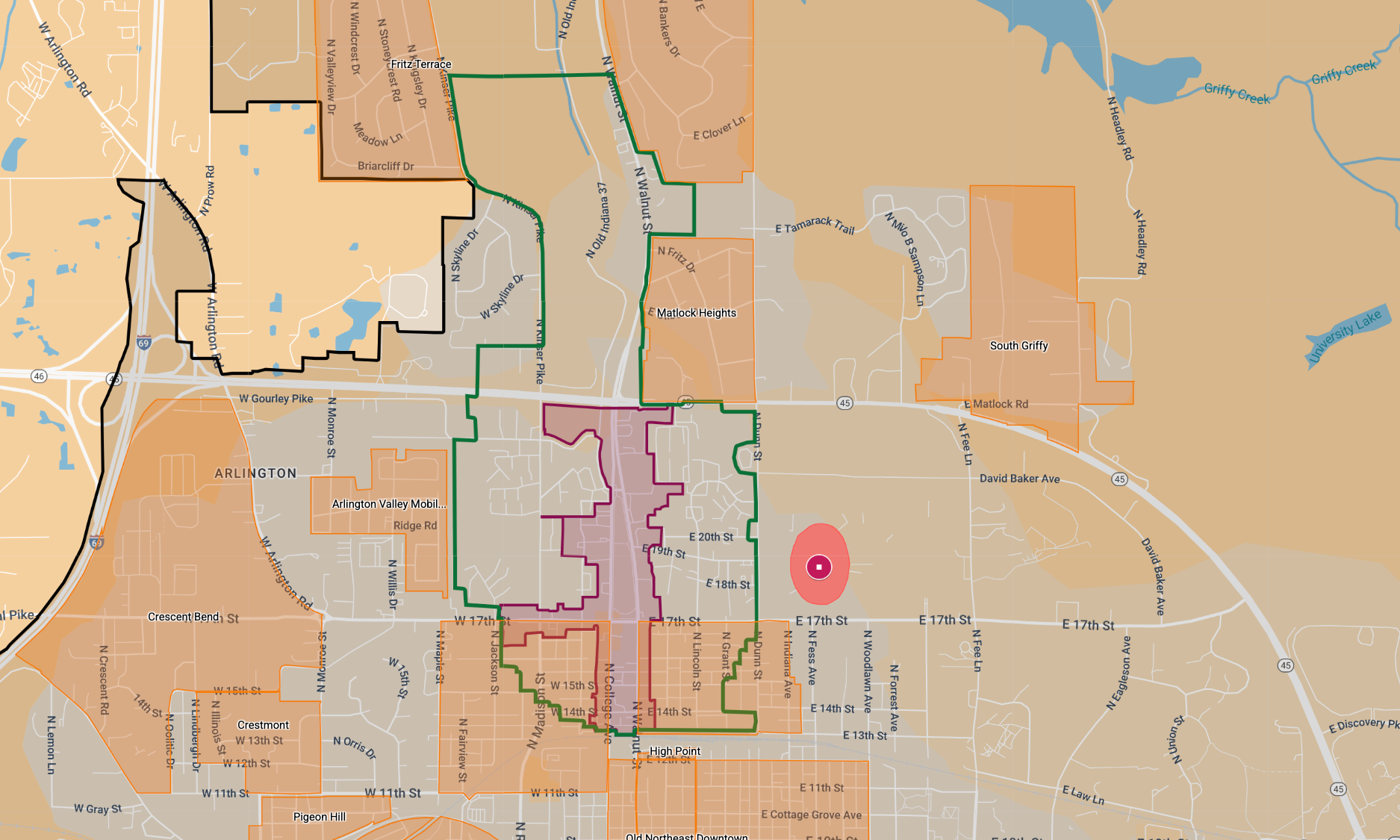

At its Wednesday (Nov. 5) meeting, Bloomington’s city council postponed indefinitely a resolution that would have officially named an area around Miller-Showers Park on the north side of town the “Stadium District.”

The idea had been to name the area through an official council action so that it could be used by businesses located in the area as a tool for marketing to visitors. The resolution did nothing more than establish the geographic boundaries and the name.

Councilmembers were not persuaded that there had been adequate outreach to residents about the boundary or the name, and some had concerns about the idea of trying to separate commercial from residential uses. Nearby residents were vocal in their opposition to the naming proposal.

A modification to the map, making the proposed district smaller, appeared in the meeting information packet on the Friday before. But that came too late to soften the objections of some neighbors, based on the idea that amplifying nearby “stadium culture” would have a negative impact on their quality of life.

The administration’s position on the impact of the named district was that it would target visitors, and would not affect residents. Director of the city’s economic and sustainable development department, Jane Kupersmith, put it like this in her remarks to the council on Wednesday: “I think this is a name that will appeal … specifically to our many, many visitors that drive our economy every year.” Kupersmith added, “And I think it will have little impact to the residents who will not even have to know that this name exists.”

A separate proposal, which is a kind of companion piece of legislation, would establish a riverfront development district, inside of which additional 3-way liquor permits would be available, beyond Bloomington’s population-based quota. But an ordinance to establish a riverfront district has not yet been introduced for consideration by the council.

The motion to postpone indefinitely is, under Robert’s Rules, essentially just a gentler way of voting down a proposal. Based on the council’s deliberations, if the naming proposal had been put to an up-down vote, it would have failed. The council had twice before postponed the naming resolution to the definite date of a subsequent meeting. But with Wednesday’s indefinite postponement, there’s no straightforward way to bring it back, except as a fresh, new proposal.

The motion to postpone indefinitely passed on a 7–1 tally. The votes did not add up to 9 because Sydney Zulich was absent. The sole dissent came from Hopi Stosberg, who had co-sponsored the resolution with the administration’s economic development department.

Part of the area to be named is included in council District 3, which Stosberg represents. But a big swath of the area was included in District 2, represented by Kate Rosenbarger, who was probably the clearest voice on the council in opposition to the proposal, at least in its current form.

Rosebarger was not in principle opposed to naming an area of the city. But about the Stadium District proposal she said, “I do not think this is ready, and so from my perspective, I’m OK postponing it … Or I’m OK voting no tonight, and then it can still come back at the beginning of 2026.”

Rosenbarger said that before a naming proposal is back in front of the city council, she wants the staff from the city’s economic and sustainable development department to attend a Maple Heights Neighborhood Association meeting, and she wants some kind of process followed for recommending and choosing a name for the district.

A district by any other name

Rosenbarger pointed out that a process was followed that resulted in the renaming of Jordan Avenue as Eagleson Avenue. Rosenbarger said, “It’s one street. This is an entire district.”

She continued, “I think it’s a lot more meaningful to everyone, like residents of our city, if they’re involved in something like that, and I think there’s a lot more buy-in.” Rosenbarger added, “I know some businesses like the name Stadium District, but I have not heard a resident say that they like it or they want to live in or near it, and that is problematic for me.”

Rosenbarger also pointed out that developing an approach to wayfinding would be difficult when the thing that gives the district its name, the university’s football stadium, is not even inside the boundaries of the district. Rosenbarger picked up on Kupersmith’s description of Miller-Showers Park as the “core” of the district. Using “Miller-Showers” as the name of the district might help with wayfinding, Rosenbarger said.

The name “Stadium District” did not evolve from a process. On Wednesday, Stosberg recounted how the name “Stadium District” was chosen after a conversation with a representative of the Greater Bloomington Chamber of Commerce, who had presented the naming concept as “Sports District.” Stosberg said, “I didn’t like ‘Sports District’ because I felt like … there are also other places in Bloomington you could call a ‘Sports District’ ...” Stosberg added, “And I thought that ‘Stadium’ was a little bit more specific, and I threw that name out as a suggestion to him—not necessarily thinking that it was going to stick. But then it apparently did.”

On the topic of the specific name, councilmember Matt Flaherty said, “What I think a good name is, or what one or two people think a good name is, or one set of constituents thinks a good name is, is not really what it’s about.” Flaherty added, “It’s about a process and about getting buy-in and a collective vision for what’s needed here.”

Connection between commerce, residential

The district naming proposal was touted by supporters like the Greater Bloomington Chamber of Commerce and the city’s economic development department as a marketing tool for businesses that would not affect residents.

But many residents objected. From the public mic on Wednesday, Tracy Bee, who is president of the Maple Heights Neighborhood Association, reported to the city council about her neighbors. “I’ve never seen them so unhappy.”

Another Maple Heights resident, Casey Green, went further, connecting the proposed district to what she called “stadium culture,” and listed out a number of factors that the proposal would not address: “It does not address loss of sleep … urinating on the front lawn in the middle of the day, driving by and yelling out the window ‘liberal witch’ because I’ve reported them too many times, or grown men on my porch at my doorstep, telling me that I have no right to report them because I live so close to the stadium I know what I’m getting into, and if I don’t like it, then I need to move.”

Green pointed out that “stadium culture” bars already exist in downtown Bloomington. About the “Stadium District” name, she said, “That name doesn’t resonate and it doesn’t add anything to the narrative.” She added, “We can find common ground on a commercial district, but we cannot do that unless we are treated with at least as much dignity as every other stakeholder that has been involved already.”

Responding to the objections, Christopher Emge with the Greater Bloomington Chamber of Commerce, said, “I can’t believe what I’m hearing tonight. The ‘Stadium District’ is to help anchor a positive, upbeat vision for a corridor in desperate need for investment that helps current residents, existing businesses, that gets future investment.”

In his remarks, Flaherty picked up on the idea of commercial and residential parts of the city, saying that they need to be considered as part of a collective whole, not in isolation. The fundamental problem with urban development starting in the 1950s, Flaherty said, is that everything was conceived as isolated pods: “We thought of everything as separate—commercial here, residential, multi-family here, single-family over here, you know, business parks here.” That approach “fragments a community,” Flaherty said.

When the community is physically fragmented, it creates “highways in the middle of town,” Flaherty said. Even though the naming proposal was not about planning and zoning, the same kind of thinking that has been “wrong-headed” about zoning and planning is part of the mix in the proposal to name the “Stadium District,” Flaherty indicated.

When neighborhoods like Garden Hill and Maple Heights say that they find the name offensive and not at all attractive to them, Flaherty questioned whether the naming proposal helps make Bloomington’s identity stronger, as claimed in the staff presentation.

Flaherty wrapped up the thought, by saying, “We shouldn’t separate these things. We should think of residential, and mixed-use, and commercial as part of a whole.”

Comments ()