Start of process for possible zoning changes halted with 4–4 votes by Bloomington city council

The process to start several changes to Bloomington’s basic zoning code were teed up to be put in motion by the city council at its regular Wednesday meeting (March 12). The basic code is called the unified development ordinance (UDO).

But both resolutions, which gave direction to the city plan commission to start the process, failed on a 4–4 tie vote—at a normally perfunctory point in the council’s meeting procedure. The tie vote was on the question of whether to introduce the resolutions by having the clerk read aloud the title and synopsis.

The total did not add to 9, because Sydney Zulich was absent due to illness.

The resolutions involved a range of topics: revising sustainability incentives; elimination of parking requirements; removal of restrictions for duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes; removal of some ADU requirements, and increases to accessory dwelling unit (ADU) size.

One resolution was put forward by Matt Flaherty, the other by Kate Rosenbarger. Joining the two in support of introduction were the council’s president, Hopi Stosberg, and vice president, Isabel Piedmont-Smith. Voting against the introduction of the resolutions were Andy Ruff, Dave Rollo, Isak Asare, and Courtney Daily.

Council chambers were not jam packed, but the more than three dozen people who did attend prompted Stosberg to observe: “This is more people that have been in this room for like a month.”

Complaints about local process

Chatter among some attendees in council chambers included annoyance about the fact that they were caught by surprise by the placement of the resolutions on the agenda of a special meeting, which had not been included on the annual calendar.

At the end of last week’s meeting (March 5), with just five councilmembers in the room—Asare, Stosberg, Piedmont-Smith, Zulich, and Rollo—the council had no objection to council president Stosberg’s plan to cancel the scheduled “deliberative meeting” in order to hold a special meeting to consider legislation instead.

Besides the authors of the resolution and the council’s president and vice president, other councilmembers apparently learned about the substance of the resolutions—which included some topics that had in the past proved to be controversial—only when the resolutions were released in the meeting information packet late last Friday (March 7).

Responding to a B Square question following the meeting, Daily told The B Square that she did not learn until Sunday that the “deliberative meeting” for Wednesday had been cancelled, and a special meeting with legislation scheduled in its place. She had departed last week's meeting before the end.

Daily described a perception among some residents that a final vote on the UDO change could be undertaken that night, which was not accurate. But she voted against the introduction of the resolutions, because she didn’t want to do something to make people “less trustful” of the council.

[Added at 9:55 a.m. on Thursday, March 13, 2025: Zulich responded to a texted question from the B Square the following morning: "It’s a tough vote because as much as I am an advocate for more types of affordable housing, the way we accomplish our goals matters. It is not good governance to spring a piece of legislation on the community and our colleagues with less than a week’s notice. I, along with several other councilmembers, was also not informed of the full scope of the legislation until Friday. We can’t claim to be transparent, and turn around and make decisions in this way."]

Reached by phone after the meeting, Rollo told The B Square that he read the packet on Saturday, and described how the resolutions had “landed like a grenade.” To address up-zoning would require more deliberations with other councilmembers and planning department staff, to “really build something from the bottom up,” Rollo said.

Rollo told The B Square that he opposed introducing the resolutions for two reasons—the process that led to placement of the resolutions on the agenda, and the substance of the proposal to increase density in older neighborhoods. Rollo has consistently opposed allowing duplexes and higher density forms in areas that have traditionally been zoned only to allow single-family houses.

Attendees of Wednesday’s meeting included recognizable faces from hearings that were held half a dozen years ago, as well as more recently—both for and against increased density in older neighborhoods.

In Bloomington, the topics of zoning and housing have been bitterly controversial at least since 2019, when the city council voted in November of that year not to allow plexes in areas historically zoned just for single-family residential. That was followed less than two years later, in May 2021, by a UDO change allowing duplexes as a conditional use in some districts that were previously zoned for just single-family residential.

The planned structure of debate was presented onscreen by Daily, who is the council’s parliamentarian.

15 minutes of presentation of the legislation

5 minutes of response from the Planning and Transportation Department

5 minutes of response from the Office of the Mayor

5 minutes of response from the sponsor

45 minutes of questions from council members

60 minutes of public comment

30 minutes of councilmember comment

The proposal to allow a total of 2 hours and 45 minutes for each of the resolutions required a vote to suspend the ordinary rules—which would have allowed even more time for deliberations. Suspending the rules requires support from a two-thirds majority of councilmembers, that is, at least six out of nine. The vote to suspend the rules failed: 5–3, with Asare, Rollo, and Ruff dissenting.

Bloomington mayor Kerry Thomson attended Wednesday's meeting, to use her allotted time under the proposed structure of debate, but as it turned out, none of it took place.

Thomson told The B Square she found out about the resolutions at the same time as the general public—when the meeting information packet was released after 5 p.m. on Friday (March 7).

Reached by phone after the meeting, Thomson indicated that her administration would be rolling out some kind of public process to try to build a consensus on how to address the challenge of adding more housing to Bloomington.

That public process will likely be influenced by classwork that Thomson, planning department director David Hittle, and HAND director Anna Killion-Hanson are doing through the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies Mayors’ Institute on City Design (MICD) Mayoral Fellowship, which works with the Just City Lab at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. The fellowship is supposed to "introduce mayors and their staff to planning and design frameworks—beyond housing supply and demand—that maximize all city resources to support the broad range of housing needs faced by a broad range of city populations." Some leaders of the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies participate in MICD programs, but there is no formal organizational relationship between the two.

Thomson told The B Square: “Our final project, actually, is all on how to create a process to reform the zoning code to get the housing that we need in Bloomington.” They will be submitting their final project design in the last week of April, Thomson said.

About the way that the resolutions from Flaherty and Rosenbarger had been developed and placed on the council’s agenda, Thomson said, “Having a vote, having a discussion, before we invite creative solutions to the table formally makes the public believe that there are only two possible outcomes: yes and no.” Thomson continued: “If we are to solve the housing problem, we have to get much more innovative than yes and no.” She added, “It's going to take much more creative thought and buy-in.”

Substance of the resolutions, statutory process

The resolution that was put forward by councilmember Matt Flaherty, directs the plan commission to draft a UDO amendment that would require developers seeking sustainable development incentives to use only electricity or on-site renewable energy sources for heating, water heating, and cooking. Sustainability development incentives are ways for a developer to exceed otherwise applicable restrictions on, for example, height.

Planned unit developments (PUDs) would also be subject to the city’s sustainability standards, under the amendment that Flaherty’s resolution directs the plan commission to prepare.

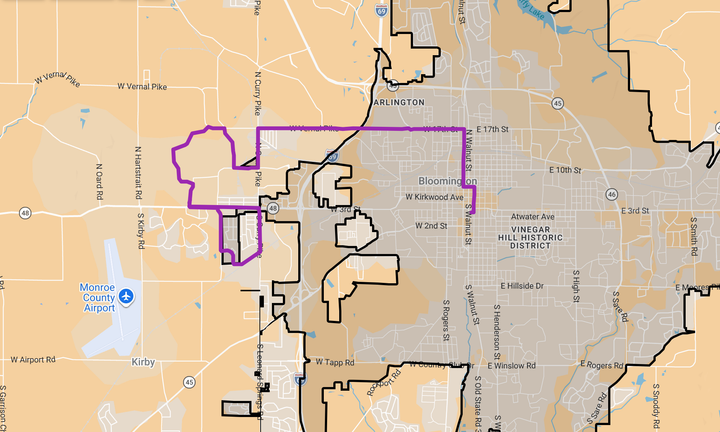

The other resolution, put forward by Rosenbarger, calls for allowing duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes as permitted uses in single-family residential zones. It also seeks to eliminate design restrictions on those housing types and ensure they follow the same dimensional standards as other primary structures in those zones. In addition, the requirement for separate utility meters in multi-unit buildings would be removed, in the amendment that Rosenbarger’s resolution directs the plan commission to prepare.

Changes to accessory dwelling units (ADUs) are also part of the mix in Rosenbarger’s resolution. The proposal would remove the owner-occupancy requirement, allow two ADUs on a single lot, and eliminate square footage limits, in favor of a footprint-based standard.

Rosenbarger’s resolution also calls for an amendment that would redefine "single-family attached dwellings" to include townhouses and rowhouses, as long as no unit is stacked on top of another. Finally, Rosenbarger’s resolution calls for easing restrictions on cottage developments by removing size limits, increasing density allowances, and making other changes to encourage their construction.

Cottage developments are defined in the UDO as: “A cluster of at least five attached or detached single-family dwellings located within a common development that use shared access, parking, and common spaces.”

The resolutions direct the plan commission to prepare UDO amendments within 90 days and to submit them with a recommendation, for consideration by the city council. After the plan commission submits the amendments to the council (that is, certifies the amendments), state law gives the council a 90-day window to act.

If the plan commission’s recommendation is favorable, that is, for adoption, and if the city council does not act within the 90 days, then the UDO amendment “takes effect as if it had been adopted (as certified) ninety (90) days after certification.”

If the plan commission’s recommendation is not favorable, or the plan commission certifies the amendment to the city council with no recommendation, then a failure by the council to act within the 90-day window means the amendment is defeated.

Comments ()