Two years of Bloomington city council votes or: Local government, how lovely are thy branches!

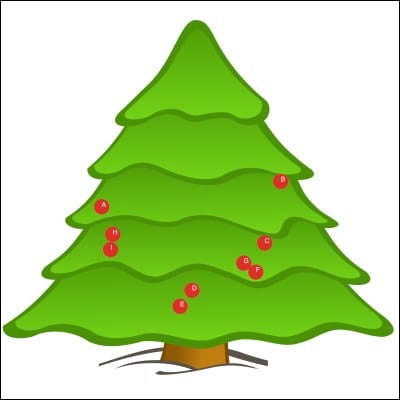

If you had to hang nine red globes on a Christmas tree, one for each Bloomington city councilmember, how would you approach that task?

What if you had to make the distance between councilmembers on the tree show how close they are politically—at least when it comes to their statistical voting pattern?

For the thousands of households across Bloomington who have been wrestling with that puzzle over the last few weeks, this column might be considered a holiday gift from The B Square.

Putting aside any impetus from the holiday season, now is a sensible time to start looking at overall voting patterns of city councilmembers.

Why?

Last Wednesday’s regular meeting of Bloomington’s city council wrapped up the first two years of a four-year city council term.

All incumbent councilmembers were elected in 2019. They were sworn in on Jan. 1, 2020.

That means all councilmembers are halfway through their terms. There’s just another year to go before it is possible for someone officially to declare a run for a council seat in 2023.

Overview of votes

Bloomington’s city council holds various kinds of meetings other than its regular and special meetings of the full council. Other meetings include committee-of-the-whole meetings and sundry standing committee meetings.

This analysis is confined just to votes taken at meetings of the full council.

For an all-Democrat council like Bloomington’s, it would be surprising if most votes were not unanimous.

And that’s borne out in the numbers: Of the 697 roll call votes tallied by The B Square over the last two years, 594 of them (85 percent) have been unanimous.

The number of roll call votes might seem a bit high, but it has been inflated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Under state law, when a meeting is held on a video-conference platform any vote has to be taken by a roll call.

So even perfunctory procedural votes like the approval of minutes require the calling of the roll. Since March 2020, all of the meetings of the Bloomington city council have taken place on the Zoom platform. That’s most of the two-year period of analysis.

Given that councilmembers are compensated for their service—they’ll earn $19,187 in 2022—it would be surprising if councilmembers were absent very often. Absences are relatively rare.

Of the 6,273 total possible voting chances for councilmembers over the two year period, as a group they’ve missed only 194 of them. For the council as a whole, that’s a collective 97-percent attendance record.

Based on B Square records, two councilmembers have perfect participation in roll call votes over the two-year period: Sue Sgambelluri and Ron Smith.

The councilmember with the highest number of missed votes was Steve Volan at 66. That works out to 90.5 percent attendance.

Besides being absent, another way of not participating in a vote is to abstain. Abstentions are customarily allowed for Bloomington city councilmembers. In the last two years, councilmembers have abstained a total of 29 times.

According to B Square records, the only councilmember who has not abstained from a vote in the last two years is Isabel Piedmont-Smith. The largest number of abstentions was tallied by Volan, who abstained from votes on eight occasions.

The city ordinance about meeting procedures of the Bloomington city council includes a provision that would allow any councilmember to insist that a colleague cast a vote:

If a member fails to vote upon any matter, any other member may raise the question and insist that the member either vote or state the reason for not voting and be excused.

The B Square has not seen that provision applied at a meeting in the last two and half years.

Voting patterns

To analyze voting patterns, the approach taken here does not identify general topic areas and ‘score’ councilmembers based on their voting record on different issues.

Instead, the idea is to consider each councilmember’s voting record as a mathematical object—a list of ones, negative ones, and zeros.

This approach does not consider the subject matter of the votes at all. Every vote is included, and they’re all weighted the same. For example, the vote on the annexation of a territory counts the same as a procedural vote on referral of an ordinance to a committee.

Because the analysis is blind to the content of the votes, it might be considered completely objective. It’s just a mathematical computation. That can be viewed as a strength.

At the same time it is a weakness, because the result tells you something about a statistical pattern of votes, but gives no insight into why the patterns look the way they do.

It’s at least a place to start.

A yes is assigned a “1”; a no a “-1” and non-participation a “0”. Non-participation due to absence or abstention are both assigned a “0.” The ‘distance’ between those mathematical objects, a kind of voting vector, is computed for each pair of councilmembers.

Having a list of distances between every pair of councilmembers is not especially useful for understanding the big picture.

In the same way, having a list of distances between every pair of nine cities would not be useful as a navigational tool. What’s needed is a way to convert those pairs of distances into a map—a two-dimensional plot with nine cities located on it.

A statistical technique called Multidimensional scaling is a way to transform the distance pairs into a map. That’s the technique that was used to generate this plot:

From this plot, three groupings of councilmembers can be discerned:

- Group 1: Dave Rollo, Susan Sandberg, Ron Smith

- Group 2: Sue Sgambelluri, Jim Sims

- Group 3: Isabel Piedmont-Smith, Matt Flaherty, Kate Rosenbarger, Steve Volan

Volan is a bit of an outlier within his own group. That’s likely due to the fact that absences and abstentions—which are assigned a “0”—work to put some distance between the absent/abstaining councilmember and every other councilmember who participated in the vote, no matter how they voted.

The maximum distance between a councilmember and every other councilmember is achieved when every councilmember participates in the vote, and there is a singleton vote of dissent or a singleton vote in favor.

The number of 8–1 votes was 14. Volan and Rollo were the sole votes of dissent for five votes apiece. Sims and Smith were sole dissenters on one occasion. Rosenbarger was the sole dissenter on one occasion. Sgambelluri, Flaherty, Piedmont-Smith, and Sandberg were never sole dissenters.

There were three votes that came out 1–8. For two of those occasions it was Volan who cast the only vote in favor. For the other one it was Rollo.

Based on the groupings, Rollo, Smith, and Sandberg (Group 1) have found themselves frequently on the same side of votes, but on different sides from Piedmont-Smith, Flaherty, Rosenbarger, Volan (Group 3).

Rollo, Smith and Sandberg were the three dissenters in all of the votes on annexation ordinances and resolutions, so it’s not surprising to see that show up in the statistical pattern.

Piedmont-Smith, Flaherty, Rosenbarger, and Volan submitted a joint memo on the 2022 budget, so it’s not surprising to see their affiliation show up in the statistical pattern of votes.

The closest votes on a nine-member council are those with tallies of 5–4 or 4–5.

For the seven 5–4 votes, Sgambelluri was the only councilmember who was on the prevailing side every time. For the six 4–5 votes, Sims was the only councilmember who was on the prevailing side every time.

In those closest tallies, the role of Sgambelluri and Sims as the swing votes probably helps account for their position in the plot, which is somewhere between Group 1 and Group 3.

Data for this analysis is available in a [Shared Google Sheet]

A next step would be to create a column to code the votes for topics—like land use, internal council business or fiscal matters.

By the end of 2022, it would be feasible to flesh out the pure numerical analysis of Bloomington city council voting with a breakdown by topic.

Comments ()